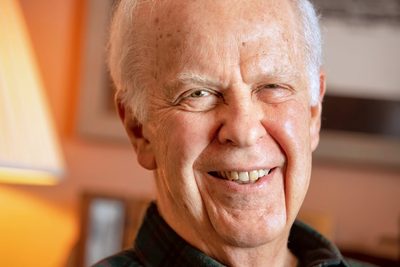

Best-selling author and spiritual activist Parker Palmer ’61 talks about the “music of mentorship.”

In early January, a 24-year-old wrote an appreciative email to educator and activist Parker Palmer ’61. The two had never met, but—like thousands of readers—the young man was stirred by the sixth of Palmer’s ten books, Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation, which became a best seller in 2000.

“He told me how the chapter on my struggles with depression changed his understanding of what was going on in his life and helped relieve his depression,” says Palmer, who lives in Madison, Wisconsin. “It helped him to have an elder acknowledge that, when you forget to stay oriented toward your North Star and grounded in your true self, you’re going to get into trouble psychologically and spiritually. His email reminded me that when we’re honest about our own stories and struggles, it can help others better navigate theirs.”

The correspondence was especially timely because, in both spirit and execution, Palmer’s most recent chart topper, On the Brink of Everything: Grace, Gravity & Getting Old, functions as a kind of senior-level sequel to Let Your Life Speak. A collection of short essays, letters, and poetry, it encourages readers middle-aged and older to stay engaged in the world by finding ways to share their wisdom with younger people. Being closer to the end of life (the brink of everything) rather than the beginning “is no excuse to wade in the shallows,” Palmer writes. To the contrary: “It’s a reason to dive deep and take creative risks.”

On the eve of his annual sojourn in the north woods of Wisconsin, where he spends a week in silent retreat, Palmer spoke in detail about what he’s come to call the dance of the generations: a mutually beneficial back-and-forth that can help mentees find their way “through the thickets of life” and that rewards those who share their wisdom with the eternal gifts of “energy, vision, and hope.”

What makes a person wise?

Wisdom is not something one can claim for oneself. We just don’t see ourselves clearly enough. One quality I find to be common among wise people is that they are always questioning what they know, usually in community with other folks who have a different life experience. They are forever learning, and having a full-bodied engagement with the world.

There’s also a lot of inner journeying involved, because we all have filters that we use to screen certain things out, often because they threaten our self-image or contradict our prejudices. In one of my introductory philosophy classes at Carleton, we studied Socrates and discussed the famous dictum “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Now that I’m 80 years old, I think I’m qualified to amend Socrates, which I rather enjoy doing. Parker’s dictum is, “If you choose to live an unexamined life, please do not take a job that involves other people, because you’re going to do tremendous damage.” And I don’t think one has to look very far to see the harm being done by people who have never taken a moment to examine their own motivations.

A wise person is someone who is able to say, “I am what I have done well and what I have done poorly. I am my gifts and my pitfalls, I am my successes and my failures.” That’s so valuable with younger people who are struggling or feeling alone.

What attributes are necessary to make someone an elder?

I’m fond of what the psychologist Erik Erikson said about the stages of adult development. The next to last stage of life involves making a choice between what he calls stagnation and generativity. You don’t have to look very far to find examples of stagnation among older people, partly because our culture can be very hard on the elderly, and we can be very hard on ourselves. I find that people who maintain vitality into old age do so partly because they have a capacity to reach out to the younger generation, which is exactly what Erikson meant by generativity.

What forces keep young people and older people apart?

As a recovering sociologist, I have a deep commitment to rejecting the notion that somehow the structures of our society are ultimately constraining and refining, like a concrete wall. What I deeply believe, because I’ve experienced it time and time again, is that individual decisions and actions can help break through most so-called walls. In this case, it’s a matter of elders owning the fact that they have the power to initiate a conversation with a younger person, a power that the younger person doesn’t believe he or she has. And key to that, I think, is getting past this notion that young people don’t want to talk to older people. That’s nonsense. I can’t imagine a person of any age who—if I approach them with an interest in learning—would say, “No, I don’t want to talk about that. That sounds like a drag.” My interest has to be genuine, but when it is, generational walls that seemed impenetrable come tumbling down.

You write about how all relationships are a two-way street. How do mentors benefit from these interactions?

When the young and the old get together, it’s like connecting the poles of a battery. The energy flows in a circuit, so there is inherent benefit to the elder. For me, it’s about staying in touch with and immersed in the world as it is at this moment. Because it isn’t the world in which I grew up.

As we grow older, it’s tempting to share our success stories with younger people and gloss over our failures. What’s the downside of that approach?

I was leading a daylong workshop at a university and, at lunchtime, I found myself at a table with about six or seven faculty members, all of whom happened to be men. Early in the meal, one of them said his parents wanted him to become a doctor, but he flunked organic chemistry, miserably, in his first semester at college. Of course, he thought his life had ended. But, as time went by, that failure turned him toward French literature, a subject he ended up loving and had been teaching for many years. So, what had felt like an utter failure became a doorway to a very satisfying life. Every man at that table had a similar story to tell. When we were about to go to our afternoon session, I asked, “How many of you have shared your story of failure with your students?” Not a single hand went up. I said, “I beg you, tell those stories, because you have young people in your classes right now who are failing at something, and they need the encouragement that comes from knowing that failure can be a path toward deep satisfaction and self-discovery.”

What are some other common mistakes made by fledgling mentors?

One of the biggest mistakes I made was imagining that I was meant to be an adviser to these young people. They hadn’t asked for my advice, but by God, they needed it, and I was going to give it to them. That’s a real killer in terms of creating a generative relationship. Begin by being interested in the other person and asking questions out of genuine interest. That creates a sort of irresistible force field of mutual respect and mutual learning.

I had three great mentors at Carleton: [chaplain] David Maitland, [religion and science professor] Ian Barbour, and [religion and Asian studies professor] Bardwell Smith. All three of these men did something that the best teachers always do: they saw possibilities in me that I didn’t see in myself, and they gave me opportunities and challenges that helped me grow into those possibilities. They gave me a life that I could not have imagined before I came to Carleton as a first-generation college student. They gave me part of themselves, and as they did, they gave me a chance to know and claim myself.

We are the sum of our experiences, good and bad.

There’s an old Hasidic tale that I’ve always loved. The rebbe says that everyone should have a coat with two pockets. In one pocket there is gold to remind us of how precious we are, and in the other pocket there’s dust, to remind us that we’re nothing. Maybe wisdom ultimately means owning and wearing a coat with two pockets.