President Donald Cowling didn’t like the view from campus. Two rundown farms stood near where the Rec Center and Spring Creek highway bridge are today. And Lyman Lakes were a marshy pasture. Perhaps worst of all, if the breeze was right, Cowling could smell rotting offal in the Northfield dump, situated where Spring Creek runs into the Cannon River.

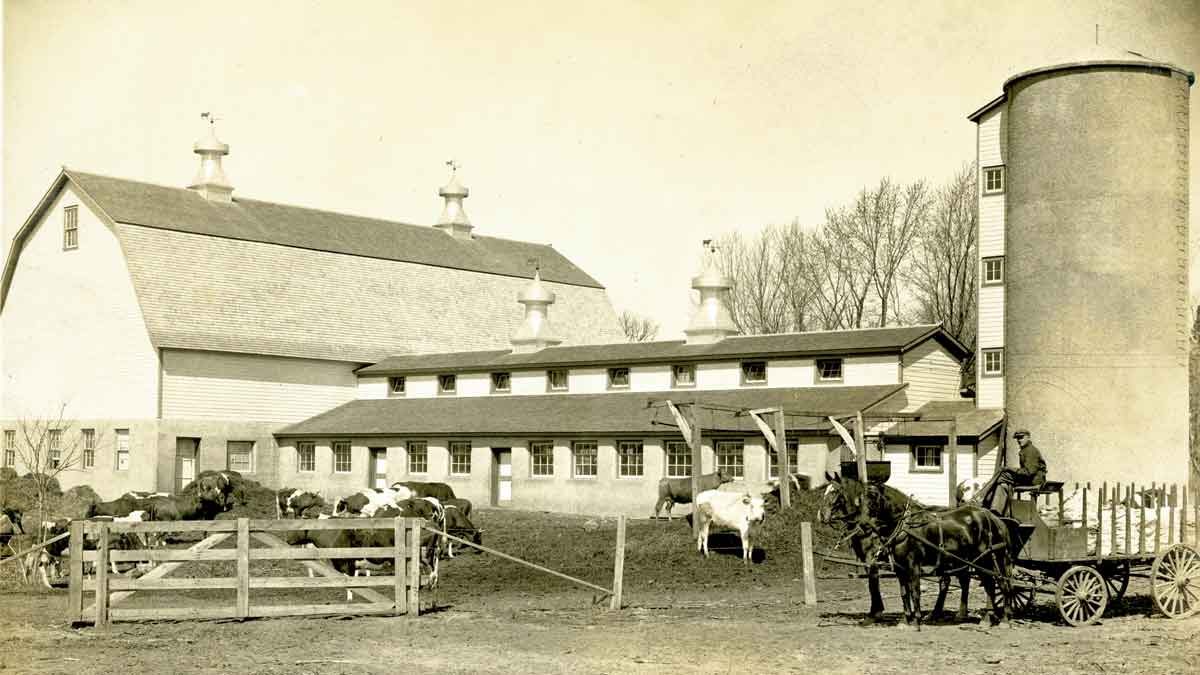

Cowling, who wanted to make Carleton the equal of the great Eastern colleges, knew he had to make the campus look—and smell—better if he were to achieve his goal. Under his leadership, the college purchased the farms north and east of campus in the late 1910s and the town dump in the mid-1920s. In 1914 the college started a dairy south of the present location of Farm House, which was built in the 1920s as housing for students who worked on the dairy farm.

For nearly 50 years, the farm supplied all the milk used in college dining halls. Besides cattle, the farm ran chicken and hog operations near Olin Farm House on the west side of Highway 19. The remainder of the newly purchased farmland was divided between pasture and crops to feed the livestock. Some of the land was designated for botany professor Harvey Stork’s arboretum. Additional land purchases in the first years of the Great Depression added to both the farm and the Arb.

No one ever said operating a dairy farm would be easy. A 1928 fire destroyed the first dairy barn, and a 1947 lightning strike killed five cows and caused another small fire on the property. A campus polio outbreak spread by unpasteurized milk in 1930 killed two students, including the brother of future Carleton president John Nason ’26. After that, all milk products used on campus were pasteurized.

The farm had successes, too. Surplus stock from the highly regarded herd was sold to dairies as far away as California. In 1960 the Holstein herd was officially classified (all stock inspected and graded) by the breed association, which further boosted its value, and animal sales provided regular income.

Cowling hoped to integrate the farm into the curriculum and hired Frederick Showers in 1917 as both the farm’s manager and a professor of agriculture. Showers’s academic post lasted two years, though he actually never taught a course. His courses—“Animal Husbandry” in the fall semester and “Plant Life on the Farm” in the spring semester—were canceled both years they were offered due to low enrollment.

Higher education for farmers was hardly novel—the University of Minnesota’s School of Agriculture was established in 1888—but it wasn’t Carleton’s central mission. The student workers living at Farm House weren’t able to run the farm due to their academic schedules and workloads. After a few years, the house was rented to outside farmworkers.

Despite its solid reputation, the farm was never a profit center, and after World War II its losses began to mount. The college hired a Rochester farm consultant to try to make the farm profitable. His conclusion: labor was simply too expensive.

The herd was sold at auction in May 1964 and, eventually, college treasurer Frank Wright ’50 recommended dissolving the farm altogether. The college tore down the barn and many outbuildings, then used Farm House and Parr House for storage before renovating them in the early ’70s for student housing. The farm fields were converted to tenant cropland. After Earth Day Field was planted in 1970, those crops were slowly converted into Arb-based conservation and restoration projects. Only an area east of the baseball field and an area northwest of Canada Avenue and Highway 19 remain in cultivation today.