The 1970s were a decade of tumultuous change: America weathered Watergate and an energy crisis; saw the rise of environmentalism, feminism, and the gay rights movement; amused itself with pet rocks, disco, and macramé; and flirted with the metric system. Some of these trends and topics swept the Carleton community like any passing fad—hotly debated and then quickly forgotten—but a surprising number of the events and forces that emerged a half century ago left indelible marks on the campus community. Here, an incomplete history.

Green Acres

Concerns about pollution, population growth, and energy use began to concern average Americans in the 1970s, eventually transforming into the modern environmental movement. As the first Earth Day celebration neared in April 1970, an ad published in the Carletonian asked students to submit slogans highlighting the “importance and urgency of checking population growth—to the environment, to quality of life, to world peace.” One example: “Whatever Your Cause, It’s a Lost Cause Unless We Control Population.” (Since 1970 the world’s population has roughly doubled.)

Interest in land conservation led Carleton to transform 10 acres of farmland adjacent to the campus into what would become Hillside Prairie. A student who was interested in water pollution conducted a study of Lyman Lakes and found that they were filled with E. coli from upstream sewers, including a handful connected to college buildings. Campus maintenance workers ultimately remedied the problem.

Students who wanted to learn about natural history, meanwhile, commandeered the Farm House. Residents grew vegetables, spun wool, and — on occasion — tanned animal skins. Even on the Carleton campus, it was a unique place: “It is not unusual to find dead birds in the refrigerator and collections of skulls adorning the mantels,” observed the Carletonian.

Not to be outdone by other schools that were celebrating the first Earth Day, Carls marked the environmental celebration with a full week of activities and events that drew national attention. Three students appeared on the Today Show with host Hugh Downs to tout the week’s focus on all things environmental.

A recycling movement also began to take root on campus. Suggested tips from an article published in the Carletonian: Don’t buy beverages in one-way containers (“no deposit, no return”); use as little tinfoil as possible; save water by putting bricks in the tank of your toilet; walk whenever possible. “Do you really need an electric can opener?” the article asked. “An electric carving knife? A refrigerator in your dormitory room?”

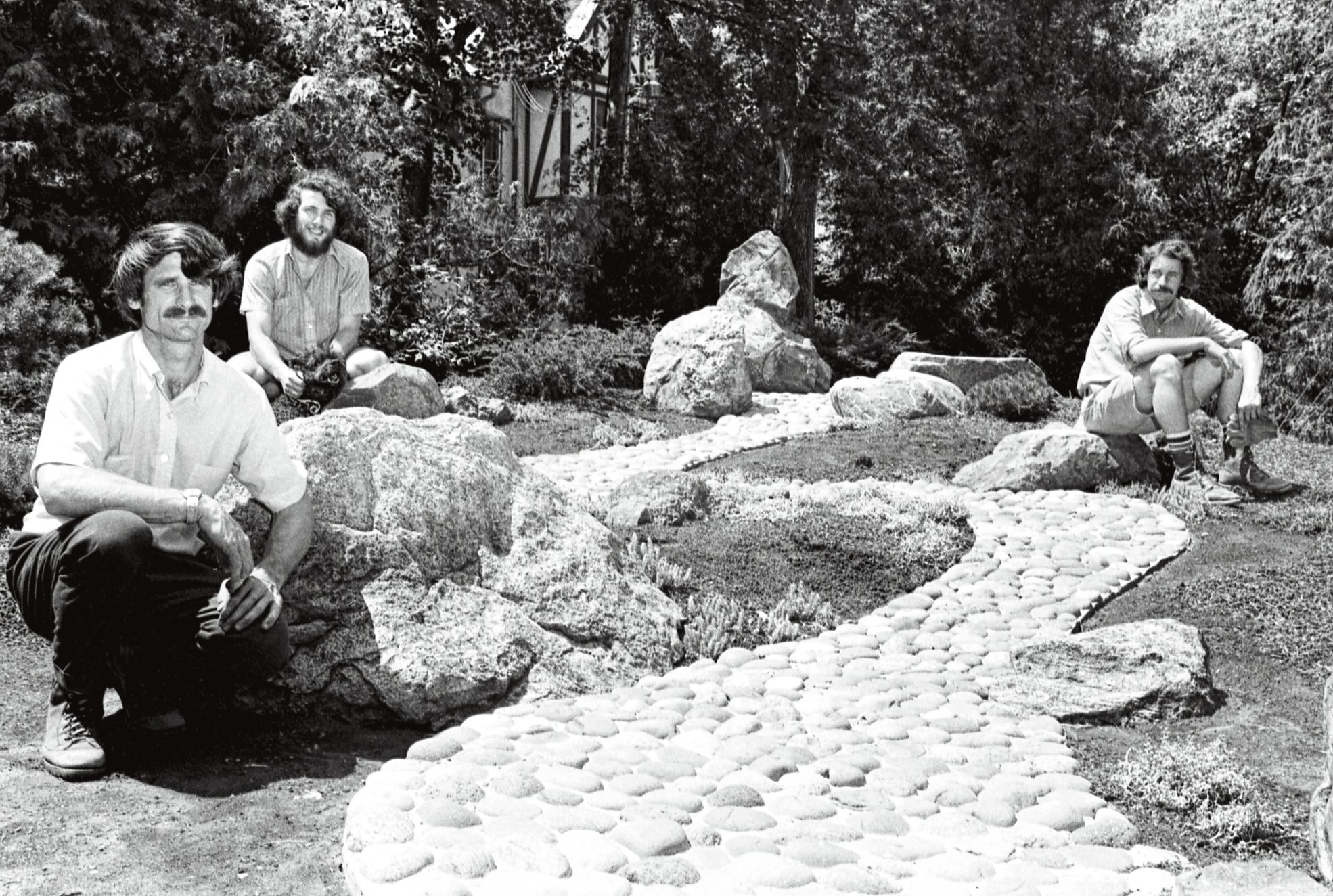

Perhaps the most lasting environmental legacy of the 1970s, however, was the Japanese Garden. Conceived by religion and Asian studies professor Bardwell Smith and designed by a young architect named David Slawson, the garden was built as a haven for reflection and relaxation, and featured pebbles from Lake Superior, American arborvitae, a teahouse-style shelter, and two stone lanterns. It was completed in 1976.

Voices of Protest

The Vietnam War spawned sit-ins and marches across college campuses in the late 1960s, and the killing of four student protesters at Kent State University by the Ohio National Guard on May 4, 1970, fanned those heated protests into a wildfire. Galvanized by the shootings and shocked by President Richard Nixon’s plans to bomb Cambodia, hundreds of Carls refused to attend classes. Kenny Bowen ’72 silk-screened dozens of T-shirts with the STRIKE logo and distributed them to fellow students. A handful of Carls then decided to organize a protest in front of the main draft-induction center in Minneapolis. “We knew we had to do something,” Kai Bird ’73 recalled in an online interview published in 2016.

Three days after the Kent State massacre, 86 Carleton students, along with political science professor Paul Wellstone and another faculty member, traveled by bus to the Twin Cities to conduct a nonviolent protest at the Old Federal Building. “For a few hours, this act of civil disobedience delayed the induction into the army of hundreds of young men, most of them the sons of Minnesota’s rural poor,” recalled Bird. “They were going off to fight a war. We were getting our college degrees from one of the best liberal arts colleges in the country.”

The sit-in did not last long: the protesters were quickly arrested, charged, and released. (Convicted of a federal misdemeanor at a later trial, most participants chose to pay a $50 fine rather than spend three days in jail.) But the debate and discontent on the Carleton campus remained: Bowen wore his STRIKE shirt nearly every day until he graduated.

Herstory: The ’70s Edition

Women have shaped Carleton’s history since its founding, but in the 1970s they began to demand long overdue changes: for more recognition, better medical services, classes that explored women’s contributions to history and literature, and more. The passage of Title IX, a federal law focused on gender parity in education, further fueled the rise of women on campus.

February 1970—Coed campus housing is allowed for the first time. Men and women move belongings across campus and swap rooms as part of “The Great Housing Peregrination,” as the Carletonian dubs it. Mixed-gender housing is generally seen as a benefit to all: “You feel unnatural going over to a girls’ floor without an excuse for being there,” John Selden ’71 tells the newspaper. “Now, we’ll get to know the girls on a friend-to-friend basis.” Another male student complains, however, that the showers in Watson are unaccommodating to anyone taller than six feet.

1971—While abortion is illegal in Minnesota, a handful of states have legalized the practice and become magnets for women seeking help with unwanted pregnancies. To ensure local women’s health and safety, a Northfield resident helps establish the Abortion Loan Fund. “The Fund’s organizers,” according to the Carletonian, “are . . . available for discussion of any problem pregnancy or abortion or any other related topic.” Both men and women are invited to apply for assistance, and 20 people reportedly draw money from the account in 1973, the same year that the Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade protects a woman’s liberty to choose to have an abortion without excessive government restriction.

January 1972—The Women’s Caucus persuades the college to retain a gynecologist for student needs. Elizabeth Mussey ’34, a doctor at Mayo Clinic and former Carletonian editor, visits the campus one afternoon each week to deal with “female problems.” Her schedule is almost immediately full.

January 1973—Jean Phillips, former dean of women turned dean of students (1965–77), writing in the Carletonian, observes: “The situation in society is only part of the problem. Women themselves are the other. Women have been conditioned to view themselves in secondary, subordinate, or submissive roles . . . and have been unwilling to commit themselves seriously to pursuit of a career or to professional development because marriage was their preferred and expected vocation. . . . And yes, we know from extensive studies that women have the same potential for accomplishment as men.”

September 1972—Eight women form the first Women’s Collective, dedicated to “understanding and confronting our common problems as sisters,” established at Furber House on Nevada Street. The house serves as a de facto center for discussion of women’s issues.

1975—Forty-five women and five men enroll in three courses—in English, history, and psychology—created to focus on women. In 1977, English professor Jane McDonnell is appointed coordinator of women’s studies—though no such major exists. Courses offered in the field are “Regionalism and Feminism,” “Comparative Perspectives on Women,” “Women in American History,” and “The New Social History.”

January 1977—Harriet Sheridan, dean of the college and English professor (1953–81) becomes the first woman to lead Carleton, after the unexpected departure of President Howard Swearer. She serves as acting president for nine months; Robert Edwards is then sworn in as Carleton’s seventh president.

Late 1970s—Physical education professor and Carleton’s first women’s athletics director Pat Lamb persuades President Edwards to change the name of the New Men’s Gym, built in 1964, to West Gym.

A Queer Start

“Did you ever have something to say, and if you didn’t say it you would burst wide open? Well, I feel that way right now. But I can’t say it to anyone face to face. I am a homosexual and if you knew how difficult it was to be a fag or queer or gay or whatever you want to call it and have everyone in the world know you, you might understand my frustration.

“I wish there were a way to get other homosexual people together—men and women—and try to understand what kind of role we play in society. Gay liberation groups have sprung up all over the country—but can you really do that here? I can’t even call a gathering of gays together here, although I’d like to, because I’m afraid, feel intimidated, very insecure.

“Maybe though, there is a stronger person out there who can do something about this. I hope. I really hope. I even hope you will print this and realize I can’t sign my name.”

This note ran in the Noon News Bulletin (NNB) on January 29, 1971. It was unsigned but didn’t go unanswered. Closeted queers at Carleton suddenly felt emboldened, willing to break their silence about their sexuality in the hopes of finding support and connections. That spring, a handful of Carls joined LGBTQ students from St. Olaf to organize Northfield Gay Liberation, a group that met in the home of a Carleton faculty member whose wife was sympathetic to their cause. “We [published] the place where it would be and said you didn’t have to be gay to come—you could be gay or you could be a sympathetic straight,” one St. Olaf participant would later recall in the Carletonian. The first meeting attracted roughly 25 people.

In November 1971 Carleton’s first LGBTQ group published its charter in the Carletonian. Its members met regularly in the basement of Skinner Memorial Chapel. “We joked that we were like the old Christians, meeting in the catacombs,” says Jerry Minkoff ’73. The gay-lib group’s meetings weren’t particularly radical or political—the push to decriminalize gay sexual activity and legalize gay marriage were still a long way off—but the gatherings did lessen the participants’ loneliness. “Before that message appeared in the NNB,” Minkoff says, “I didn’t even know if there were other gay people on campus.”

Campus Visitors

Change makers have always been drawn to Carleton, and the list of speakers who visited campus in the 1970s is impressive. The early years of the decade drew such headliners as:

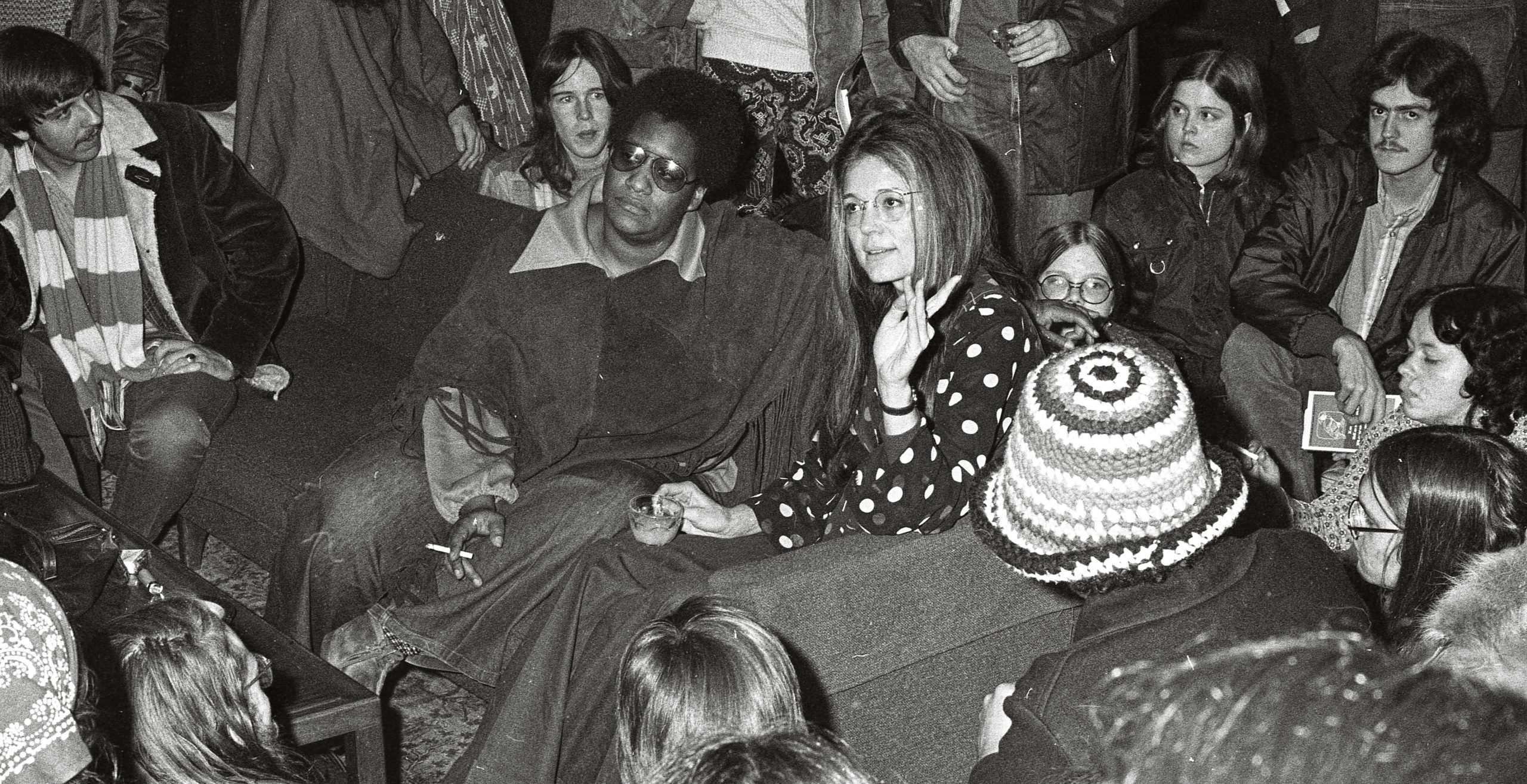

Gloria Steinem and Margaret Sloan

Famed feminists Steinem, founder of Ms. magazine, and Sloan, a political activist and speaker, packed Skinner Memorial Chapel in the spring of 1973. Opening their talk on “Sexism and Racism,” Steinem announced, “If we come here tonight and there is no trouble here tomorrow, then we haven’t done our job.”

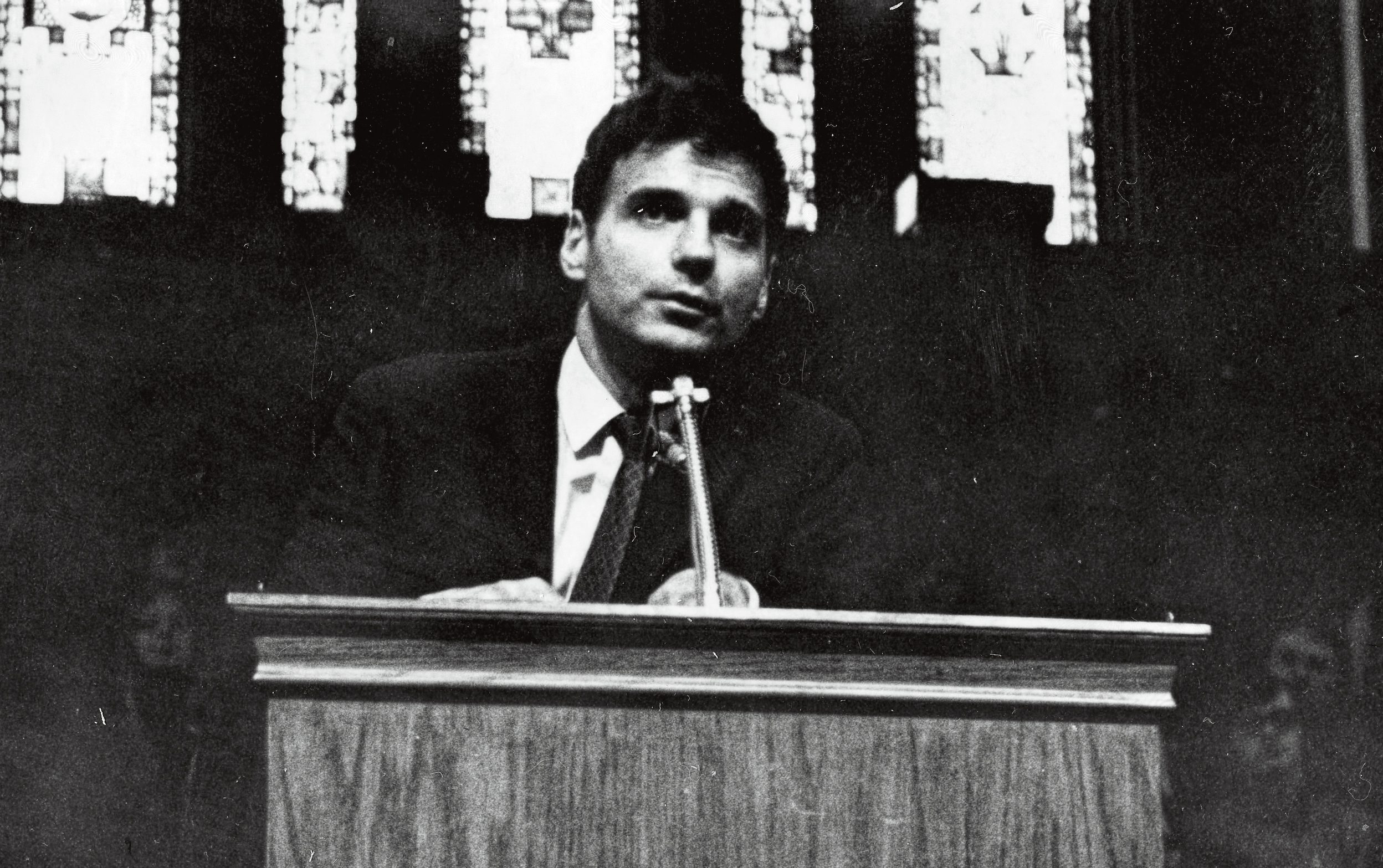

Ralph Nader

In January 1971, the consumer advocate pitched a concept he called MPIRG: the Minnesota Public Interest Research Group. Within the year, Carls had helped launch the student-run effort—the first of many PIRGs established across America. MPIRG successfully advocated for many environmental causes, including establishment of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in 1978.

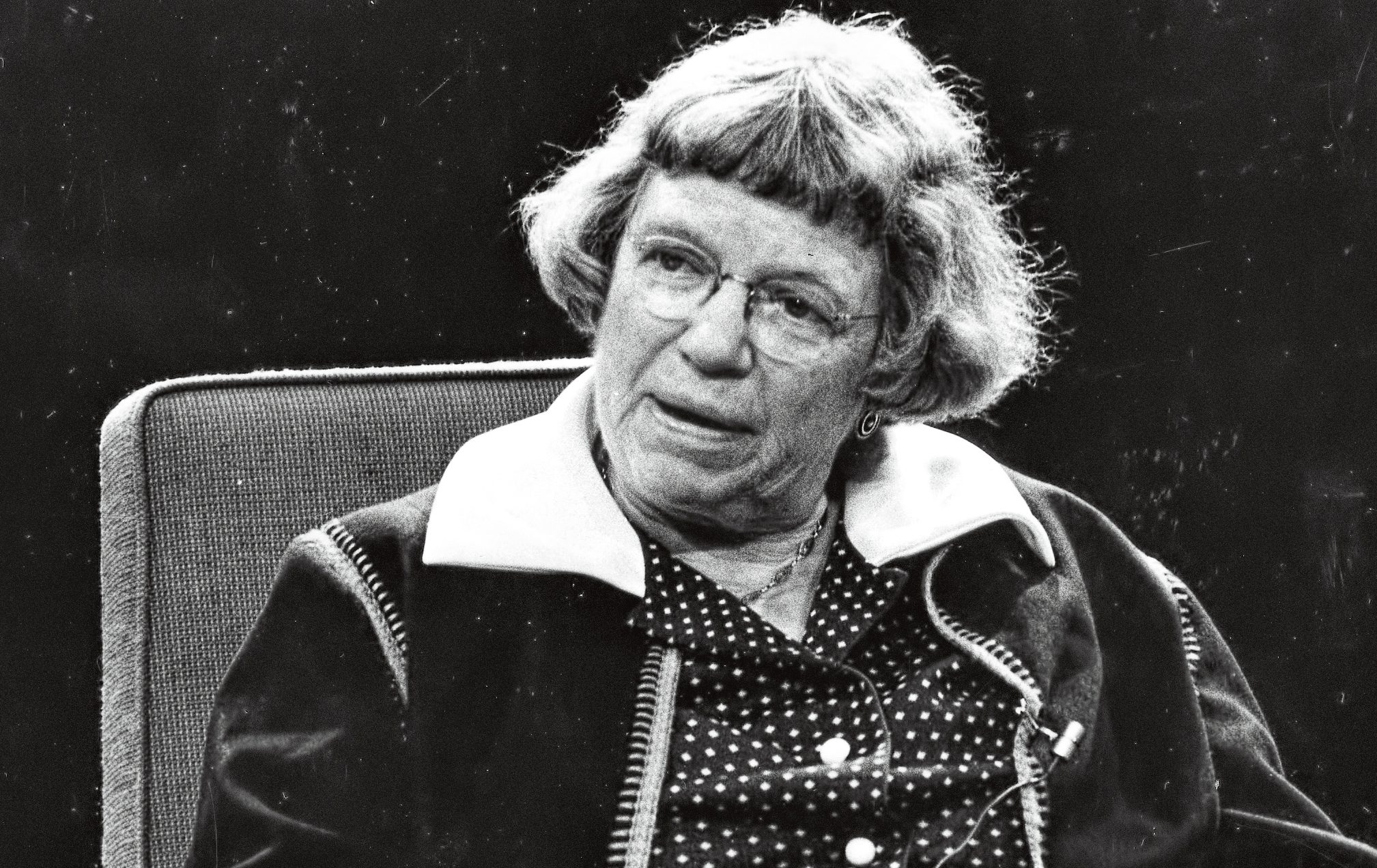

Margaret Mead

The famed cultural anthropologist spoke about the generation gap between pre- and postwar generations—but dodged most questions about feminism. The Carletonian reported on her talk but found it somewhat rambling.

Alex Haley

Coauthor of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Haley appeared before an audience assembled in Carleton’s new Music and Drama Center to talk about his research on slavery and his own family heritage. The material would later be published as Roots, a Pulitzer Prize–winning novel that eventually became an Emmy Award–winning television miniseries.

Bricks and Mortar

The college’s long association with famed architect Minoru Yamasaki—who designed the West Gym, Olin Hall of Science, and several other campus buildings before going on to work on the World Trade Center towers, destroyed in the 9/11 attacks—came to a close at the end of the 1960s, allowing others to leave their mark on the campus landscape. The first was Harry Weese, a Chicagoan whose Music and Drama Center opened to acclaim in January 1971. Consisting of two individual brown-brick boxes that connected underground, the structure housed both a concert hall and a 500-seat theater. It was designed for maximum flexibility: stage and seating arrangements could be configured in countless ways, and a pair of tall candelabra on the plaza outside were wired for loudspeakers so performances could be held outdoors. But the most buzzy element of the new design was the seating: the Arena Theater was ringed with cherry-red upholstered benches, sans armrests, most big enough to allow two (or three) patrons to snuggle during a show.

Mudd Hall of Science, the new home of the chemistry and geology departments, opened in 1976. Once again flexibility was a design priority, with emphasis on spaces that “encourage students to move easily to accomplish studies of varied nature,” according to a brochure outlining the project. “Such openness is especially appropriate at Carleton.” Linked via glass walkway to Olin (the home of biology and physics, completed in 1961), the brick building contained labs, a central stockroom, cold storage, and a workroom for “rock grinding and specimen sifting”—a considerable improvement over the departments’ former home in Leighton Hall. (The latter, erected in 1920, was renovated into classroom space for non-science departments.)

Ultimately, both buildings ran their course. Mudd was razed in 2017 to make way for a new science complex. And the Music and Drama Center, once heralded by the Carletonian as “a permanent challenge for new and, as yet, undreamed approaches,” suffered from chronic design and maintenance issues nearly from the start. The building envelope trapped moisture, and bricks regularly peeled from the exterior—among other problems. A 2014 planning report noted that the building “serves the program poorly, is only partially occupied, and must be avoided on student tours.” The center is currently empty and eventually will be torn down.

Student Space

Sayles-Hill, once lauded as the best gymnasium in Minnesota, got an overhaul in 1979, emerging as the campus’s new student center, complete with space for TVs, a snack bar, and pool, Ping-Pong, and foosball tables. A bookstore was added too. The rededication was celebrated with champagne and a monumental cake decorated to look like a scale version of the building.

Fun and Games

Carls have always prided themselves on their creativity and sense of humor, but the pranks and pastimes of the 1970s were particularly memorable—and not a little weird. A sampling:

1977—Meter Made

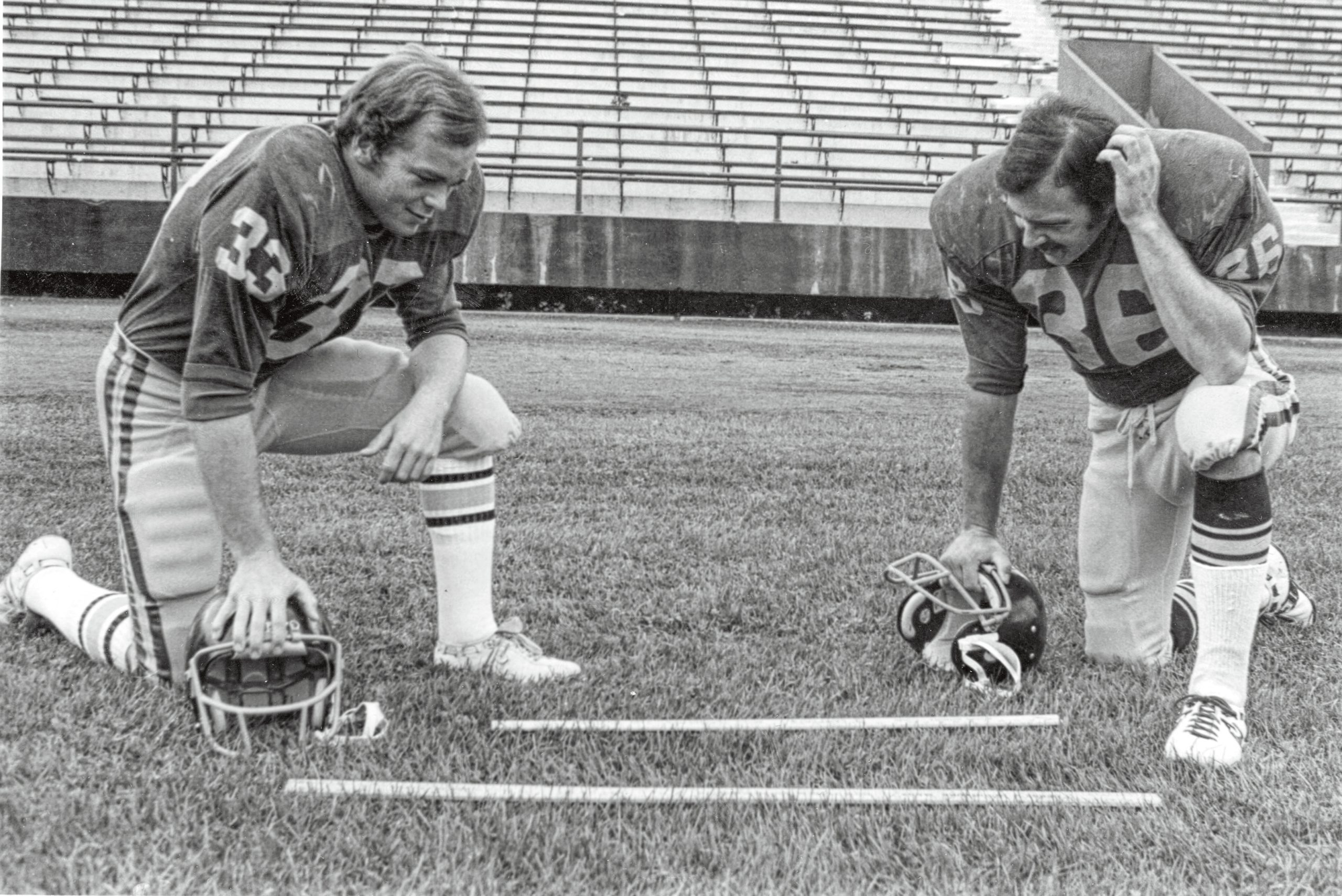

A fierce debate over use of the metric system roiled America in the 1970s. Carleton made its own contribution to the not-someasured conversation in 1977, when the Knights faced down their longtime football rival, the St. Olaf Lions, during the first and only Literbowl. Dreamed up by Carleton chemistry professor Jerry Mohrig, who was teaching a course on metrics, the NCAA–sanctioned game was played on a 100-by-53-meter gridiron, and players’ heights and weights were listed in centimeters and kilograms. The event drew a capacity crowd of 10,000 to Laird Stadium and garnered national media attention, including cheeky articles in Sports Illustrated, the Wall Street Journal, and other news outlets. (“What will become of the foot-long hotdog?” wondered the Rocky Mountain News in a piece about the tilt.) In the end, the Lions clobbered the Knights, winning 42–0. Ultimately, the metric system would lose as well. Today, the United States is one of just three countries, alongside Myanmar and Liberia, that doesn’t use what’s now referred to as the International System of Units.

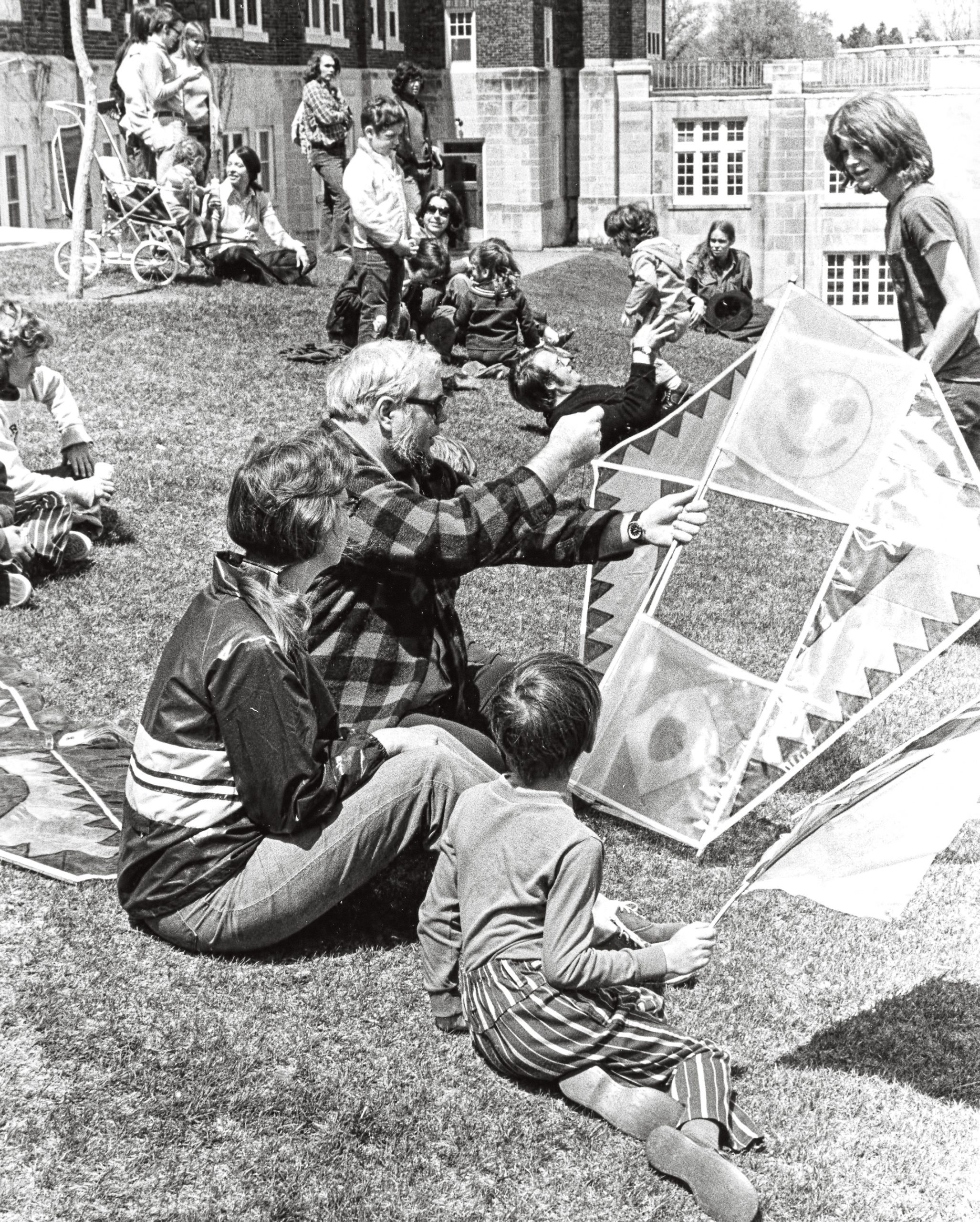

April 1974—Airborne Festival

Carleton’s art department sponsored an Airborne Festival, showcasing contraptions that can fly the highest and longest—with additional prizes for those judged “most flamboyant, most sophisticated, and most (and least) aesthetic.”

February 1974—Female Streaker

Freshman Laura Barton ’77 crashed the curtain call of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure wearing only socks, tennis shoes, and a ski mask. Heralded as America’s first female streaker, she was later identified and interviewed by numerous media outlets. “I’ll probably be crazy as an old lady, too,” she told the Associated Press.

1973—Faculty & Staff Running Club

Jim Fixx’s bible The Complete Book of Running wouldn’t be published for several years, but a handful of long-legged Carls convened at Laird Stadium at 11:30 each day to choose a route for a midday run. Some members of the all-male group were training for marathons; others just enjoyed the camaraderie. Faculty member Robert Bonner later recalled how his new Nike trainers made a difference: “I remember thinking I could fly. They were such a dramatic improvement. Before that, I was running around in tennis shoes.”

Black Renaissance

Carleton hired its first Black admissions officer in 1968 and began recruiting applicants from underrepresented groups. In the late 1960s, campus African Americans had formed political groups and successfully lobbied for a Black studies program. By the early 1970s, Black students constituted roughly 10 percent of the student body and formed Blackcentric organizations focused on theater, music, dance, and even comedy. Among them:

Ebony II

Organized in 1973 as a way to mark Black History Week, this dance troupe quickly became a campus fixture, lasting for more than 30 years. “There was a lot of talent on campus in those years,” says Debra Carter McCray ’76, who founded the student-run group. Ebony II toured the state and appeared at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

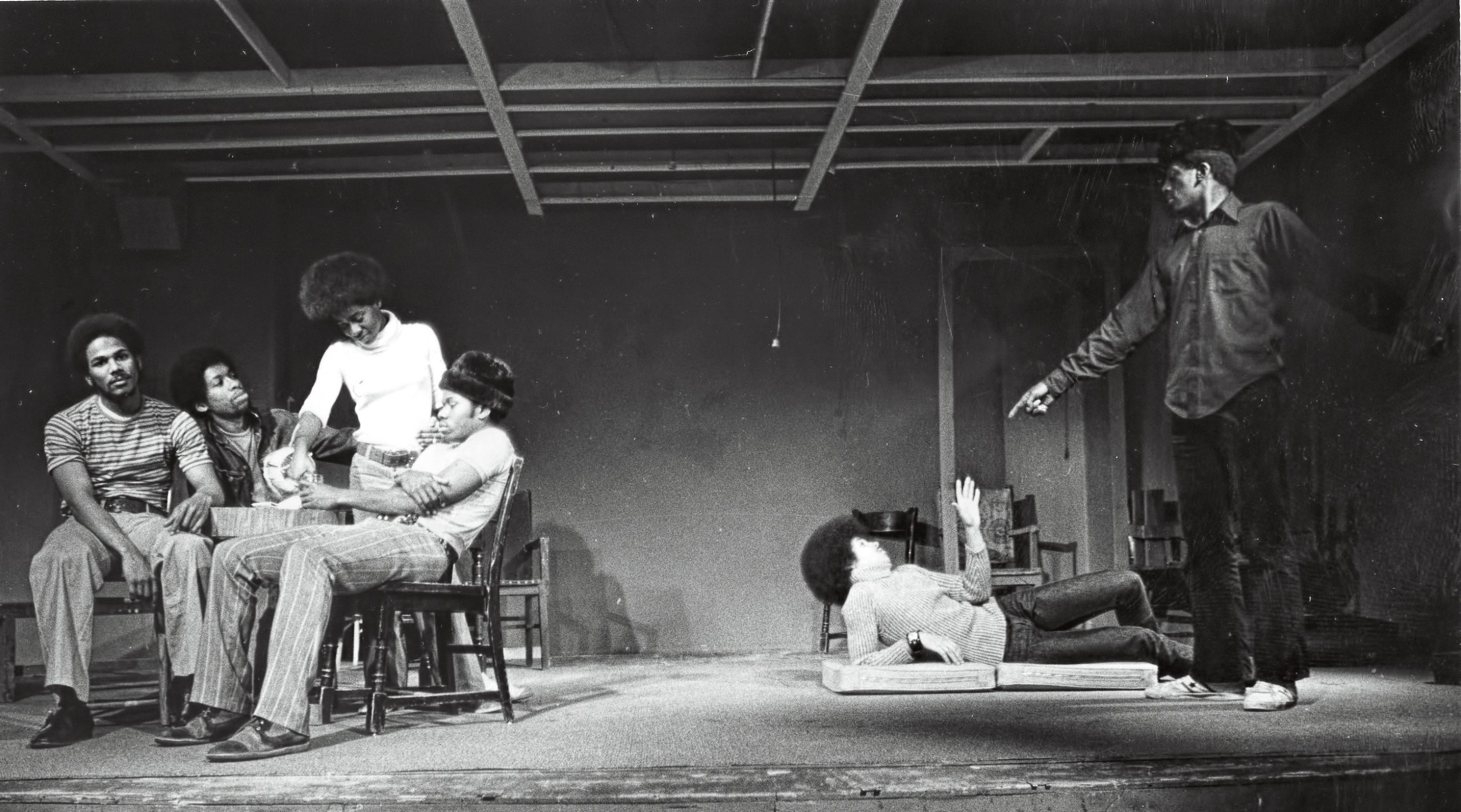

Black Repertory Workshop Theatre Troupe

Begun by aspiring screenwriter Gerald Lockhart ’72, this workshop presented original works that centered on Black life. “The story was always Black, whether it was set in New York or Watts or Chicago,” Lockhart recalls. “We wanted to pull back the curtain and show what was happening.” Later renamed Black Dramatic Arts Group, the troupe went on to perform such plays as No Place to Be Somebody and A Raisin in the Sun.

Inspirational Movement

Amens echoed across campus when Michael Monroe ’74 organized the college’s first gospel group. Inspirational Movement debuted in 1972 and often performed alongside Ebony II and the New Light, a Black choir from St. Olaf.

Research assistance for this article was provided by Carleton digital archivist Nat Wilson. The editors would also like to thank all the editors and writers who work and have worked on the Carletonian. Their writing and images capture on-campus moments that would otherwise be lost.