In his most recent book, Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines, Jack El-Hai ’79 examines the airline’s impact on 20th-century business, travel, and culture—beginning with its earliest flights in 1926, carrying mail to Chicago, through its acquisition in 2010 by Delta Airlines.

The following excerpt discusses the airline’s launch of the double-decker Stratocruiser, which it trumpeted as a “castle in the air.”

It arrived in Northwest’s fleet more than a year late, but in August 1949 customers got their first look at the Boeing B-377, nicknamed in moderne style the Stratocruiser, a wondrous double-decked airliner.

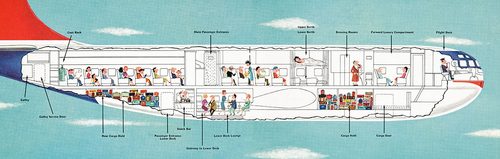

Capable of carrying up to one hundred passengers and powered by four engines more than twice as powerful as those on Northwest’s DC-4s, these pudgy planes cruised at more than three hundred miles per hour and cut eight hours off the flying time from the U.S. mainland to Tokyo.

Capable of carrying up to one hundred passengers and powered by four engines more than twice as powerful as those on Northwest’s DC-4s, these pudgy planes cruised at more than three hundred miles per hour and cut eight hours off the flying time from the U.S. mainland to Tokyo.

Northwest was the only U.S. airline to introduce Stratocruisers, acquired at a cost of $20 million, to domestic service, and by the following year the planes were flying most of the airline’s long domestic routes. The Stratocruiser figured prominently in a $35 million equipment improvement program that president Croil Hunter had pushed through three years earlier, funded by loans and special issues of preferred stock. Hunter pinned his hopes of attracting new business on the seductions of the aircraft, of which Boeing manufactured only fifty-six.

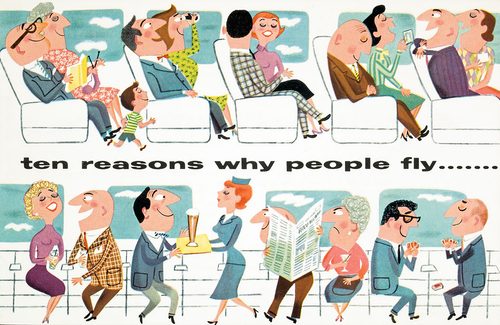

Passengers loved the planes for the unheard-of comfort they offered, and they quickly took a prominent place within the lore of luxury commercial flying of the late 1940s and early 1950s. The plane’s popularity came at a great financial cost to Northwest, however.

Employees joked that the Stratocruiser, a notorious fuel guzzler, could turn a profit only when carrying 110 percent of its passenger load.

Bob Fliegel was among the earliest Northwest passengers to board this airliner in its premier year. The flight burned into his memory.

“Looking out the terminal window onto the tarmac, I saw the magnificent double-decker Stratocruiser. A stunningly gorgeous stewardess . . . dressed in a smartly tailored Northwest Airlines uniform and stiletto heels, greeted us at the base of the stairway,” he wrote nearly fifty years later. Fliegel was nine years old when he began this momentous experience of his boyhood.

And this boy was hungry. “The [food] trays plugged into holes in the arms of the seats, as there was too much distance between the rows to have allowed the seat-back tray-stowage system of today,” Fliegel remembered. “Meals were served on real plates, placed on small white tablecloths—and passengers ate with real flatware, not plastic forks.”

The main attractions of the plane, however, were not at the assigned seat. “The Stratocruiser’s lower-deck lounge was accessible via a short stairway from the passenger compartment,” Fliegel recalled. “Though the lounge did not run the full length of the aircraft, it featured seven seats available for sale in addition to the chairs and tables available to all.” The lounge, which seated fourteen in “the intimate, comfortable atmosphere of a very luxurious cocktail lounge,” wrote the Minneapolis Tribune’s Cedric Adams, boasted built-in glass racks, glass holders for each seat, and cushy furnishings “that would make an ideal addition to anybody’s amusement room.” (When flying Northwest’s Far East service, the lounge offered chopsticks and became what was called “the Fujiyama Room.”)

The main attractions of the plane, however, were not at the assigned seat. “The Stratocruiser’s lower-deck lounge was accessible via a short stairway from the passenger compartment,” Fliegel recalled. “Though the lounge did not run the full length of the aircraft, it featured seven seats available for sale in addition to the chairs and tables available to all.” The lounge, which seated fourteen in “the intimate, comfortable atmosphere of a very luxurious cocktail lounge,” wrote the Minneapolis Tribune’s Cedric Adams, boasted built-in glass racks, glass holders for each seat, and cushy furnishings “that would make an ideal addition to anybody’s amusement room.” (When flying Northwest’s Far East service, the lounge offered chopsticks and became what was called “the Fujiyama Room.”)

Adams also took note of the bathrooms. “The ladies’ powder room has the elegance of the Waldorf,” he wrote. “Fluorescent lighting, gold mirrors, plenty of space for primping. Even the men’s room has been given a lot of attention. Ample room for shaving, for instance.” After shaving, a gentleman could complete social plans after landing using commercial aviation’s first air-to-ground telephone.

But Fliegel, the nine-year-old, focused his attention elsewhere.

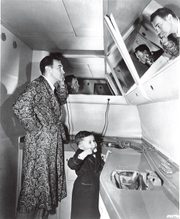

“During periods of relative calm,” he wrote, “children enjoyed climbing [the stairs] between the two decks.” These spiral stairs left a strong impression on passengers. “I’ve been trotting up and down stairs at a height of 15,000 feet, and my head is still in the clouds,” wrote columnist Ed Creagh of the Seattle Times in the Stratocruiser’s first month of operation in the Northwest fleet. “Trotting up and down? That’s right. In a plane. Stairs in a plane. Maybe that leaves you several degrees under the boiling point, but you are younger. You’re at peace with the 20th century. To me it’s frightening.” He concluded: “What’s next? Escalators?”

When roaming the stairs tired passengers, other comforts were available. “Passengers in the first few rows had access to overhead bunks that pulled down from the area of today’s carry-on stowage compartments,” Fliegel wrote. “I remember the mattresses as thick and comfy. For privacy you pulled a curtain across the bunks—it was quite a trick to get into one’s pajamas in such a restricted space, but at age nine I was a skilled (and small) contortionist.” Company lore tells of a flight in which the crew was having trouble maintaining pressurization in the cabin. “The entire plane was searched for air pressure leaks, until one man in a berth was found with the emergency exit open slightly,” a Northwest press release reported. “‘I always open the window when I go to bed,’ he explained.”

When roaming the stairs tired passengers, other comforts were available. “Passengers in the first few rows had access to overhead bunks that pulled down from the area of today’s carry-on stowage compartments,” Fliegel wrote. “I remember the mattresses as thick and comfy. For privacy you pulled a curtain across the bunks—it was quite a trick to get into one’s pajamas in such a restricted space, but at age nine I was a skilled (and small) contortionist.” Company lore tells of a flight in which the crew was having trouble maintaining pressurization in the cabin. “The entire plane was searched for air pressure leaks, until one man in a berth was found with the emergency exit open slightly,” a Northwest press release reported. “‘I always open the window when I go to bed,’ he explained.”

Did the Stratocruiser receive any low marks? “The ride was often bumpy, the cabin smoke-filled, and the cross-country flights longer than we care to remember,” Fliegel recalled. While the Stratocruiser let passengers fly like royalty, it demanded queenly treatment to keep up in the air, which eventually led to its removal from the Northwest fleet. A maintenance supervisor remembered it as “a lovely plane, but you couldn’t charge enough to pay for the mechanical and fuel bills for it. It sucked gas and it sucked maintenance.” It was, according to one company executive, “a stockholder’s nightmare but a passenger’s dream.” The last were retired in 1960.

A year before the end, though, Northwest’s vice president of sales, Gordon Bain, engineered one final publicity coup and advance in luxury for the airline’s Stratocruisers. The Northwest Organ Company of Minneapolis installed a Lowrey organ in one Stratocruiser lounge, and notable organists of the Upper Midwest took turns playing such standards as “Autumn Leaves,” “My Funny Valentine,” and “Nearer My God to Thee” in flight.

The Stratocruiser soon sang its swan song.

Editor’s note: Bob Fliegel is a member of the Carleton Class of 1961.

Excerpted from Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines, University of Minnesota Press. Copyright 2013 by Jack El-Hai.