For more than 30 years, a unique department at Carleton explored the cross-disciplinary importance of biographical study.

I HAVE LONG BELIEVED in the power of biography. The two book-length works I’ve written have led me on a series of memorable journeys. Putting them together taught me how to make sense of someone else’s life, even when I have trouble making sense of my own; how to separate strands of story embedded in unruly archives; and how digging deeply into a person’s motivation is one of the best ways to tell a great life story.

These are all authorial benefits, of course. Only a writer would likely care. Which is why, over the years, I’ve often found myself wondering what readers gain from biographies and what they most want from them. Is it the pleasure of a good yarn well told, a glimpse of the past, or simply the luxury of losing themselves in the drama of another person’s experience? Or is it based on something else altogether?

A few years ago, after I finished writing The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII, I came across a surprising bit of news about my alma mater. During the early decades of the 20th century, Carleton not only offered a series of courses about biography, it had the only Department of Biography in the world.

I tried to imagine biography as an academic discipline. Surely Carleton wasn’t training students to become biographers. Perhaps professors were approaching the subject just as they approached psychology, geology, music, and other liberal arts majors—as paths leading students toward learning critical thinking while they acquired valuable specialized knowledge. I also wondered if finding out more about Carleton’s approach would help me better understand readers’ motivations.

Being a biographer, I began my search in the Carleton Archives.

THE COLLEGE’S REPOSITORY of its own history is housed in a quiet suite of rooms in the lowest level of Gould Library. It was there that I sized up the information on the Department of Biography that had been preserved. The stack of files was seven inches thick. It told a story that began with a flash of brilliance and then, after 35 years, flickered out.

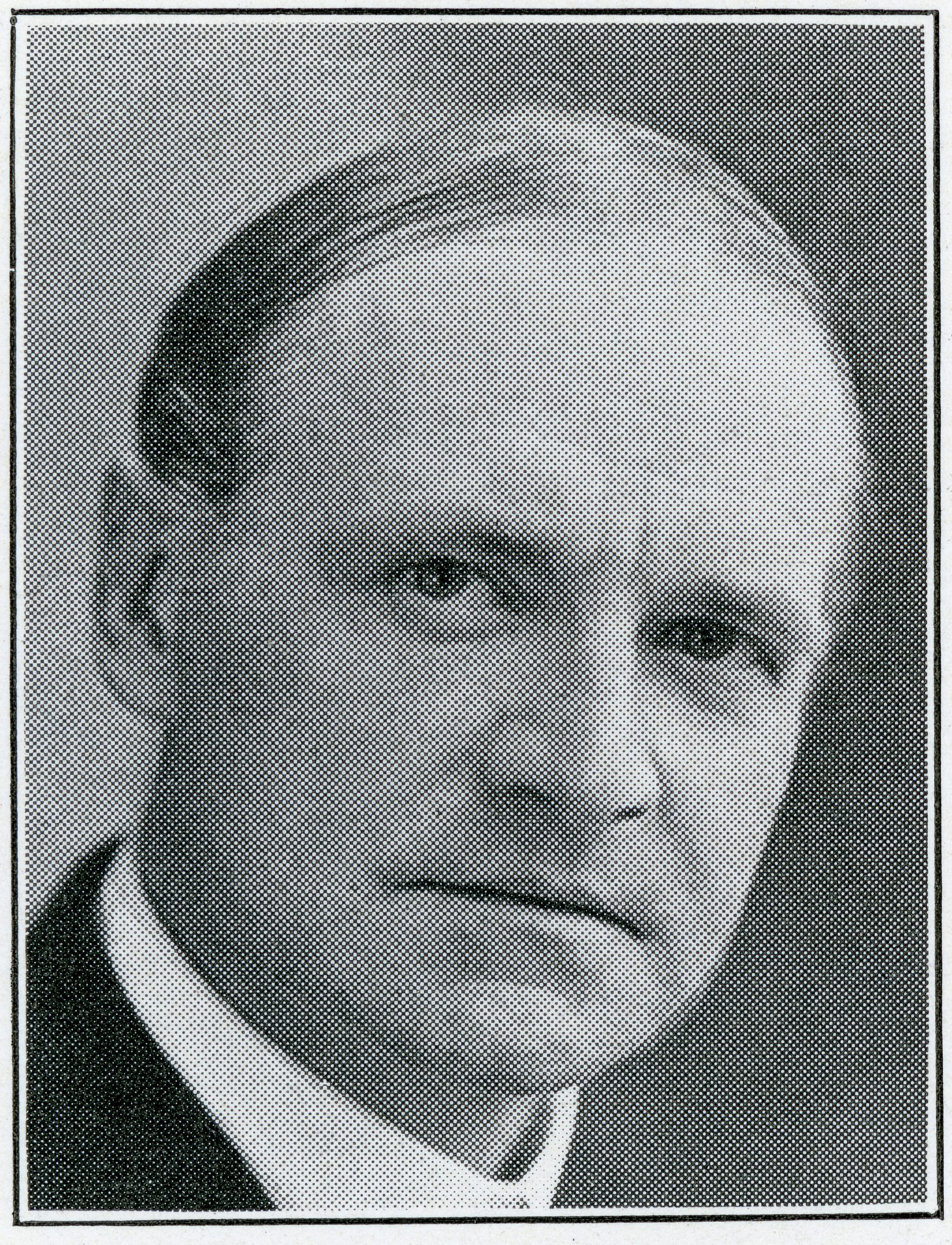

The department’s original protagonist was Ambrose White Vernon, who began his career in academe as a professor of biblical literature and congregational pastor at Dartmouth. A man with an intense, birdlike gaze, Vernon moved on to lead the college church at Yale Divinity School, and then, in his late forties, served as pastor at the Harvard Church in Brookline, Massachusetts.

In this last position, Vernon became convinced that biographies about individual lives could reveal truths about humanity with specificity and vividness, in ways superior to what he regarded as the sterility of studies that were too often short on life and action.

It was an unusual conviction, and few other academic people shared it. It arose from Vernon’s faith. He believed that everyone had a divine purpose and that by examining the paths great men chose (men, almost always, were of chief interest at the time) students could better view the flow of such wide-ranging fields as history, religion, philosophy, classical studies, economics, psychology, and political science.

In fact, Vernon considered biography the ultimate multidisciplinary activity—although there’s no record of his using the term. Because lives were inherently interesting, he maintained, a significant person’s biography could illuminate historical settings, intellectual and cultural trends, and religious practices, as well as the subject’s overall influence.

Students could also enlarge their intimate understanding of an individual life into a better appreciation of the values and hopes important to all of humankind at any given time. People who once walked the earth could serve as a procession of exemplars capable of animating any era or field of study. As biographical subjects lived on the page, they gave readers the chance to absorb the spirit of humanity.

I had never thought of my own biographical subjects that way. It intrigued me to consider depicting my nonfictional characters as representatives of more than themselves.

EVEN THOUGH Vernon had not yet taught biography anywhere, his reputation as a promoter of the value of biographical study began to spread. When Carleton president Donald Cowling (in office from 1909 to 1945) learned about the academic renegade, he reached out and, in 1919, offered Vernon a faculty position to further explore the possibilities and rewards of biographical study—and to establish the world’s first academic department devoted to it.

Vernon jumped at the opportunity and duly formed Carleton’s Department of Biography, in which he served as the sole faculty member. During his very first semester, Vernon taught “Great Personalities of Antiquity and the Personality of Jesus” and then followed with “Great Personalities of the Middle Ages and Christian Letters of the First Centuries.”

Vernon typically devoted a couple of weeks to the life of each figure in the purview of his courses, lecturing and inviting discussions. Students read article- and book-length texts on those figures and their times. Vernon also required students to supplement his reading assignments with their own independent reading. An observer noted Vernon’s “well-nigh illegible commentaries on every single paper, paragraph by paragraph, always asking for evidence.” Vernon wanted students to “make up their own minds, not sponge up ‘opinions.’ ”

During the 1921–22 academic year, Vernon taught three courses a semester, in which a total of about 70 students enrolled. He stocked the college library with biographical works. In his department’s annual report that year, Vernon asked for nothing more than “a room done in soft colors upon which pictures may be hung advantageously,” as well as an assistant to help him read the thousands of pages of papers his students generated.

The next year, the department’s enrollment grew to 144. Vernon, a serious scholar and a witty man, was a popular figure on campus. “He was at home with all the great literature of the ancient and modern world,” John Beveridge ’26 recalled. “His lectures were the product of much research, and he had a masterful command of language. He was polite to the point of being deferential; but he did not hesitate to say what he thought.”

VERNON’S DECISION in 1925 to leave and establish a biography department at Dartmouth was a blow to Carleton. “Mr. Vernon’s courses were Mr. Vernon,” observed Theodore Wedel, an English professor who agreed to keep the department going as temporary chair, “and he had the advantage of being enabled to deal in the classroom with that wide sweep of knowledge in all fields which he as a cultivated man had acquired. . . . Mr. Vernon’s biography department simply gave to this liberalized view of teaching a new name.”

Carleton struggled ahead. Three different professors taught three different biography courses each semester. Wedel called the department’s activities in Vernon’s absence “a shadowed existence.” He feared the department, though undeniably valuable, was becoming an academic orphan, a multidisciplinary misfit at a time when other departments were establishing their territory and solidifying their boundaries. Today multidisciplinary approaches are common and encouraged at Carleton, but not so in the 1920s. Wedel wrote to Cowling, “A course in biography would be laughed at in most of our departmentalized universities. Yet I think it deserves no laughter.”

The department went into hibernation for a few years, but Wedel relaunched the department in 1930–31 with “Representative Americans,” “Representative Moralists,” and “Representative Victorians.” Wedel clearly enjoyed what he was teaching, because he changed his title from professor of English to professor of biography in 1930 and kept that title for four years, when his leadership of the department ended.

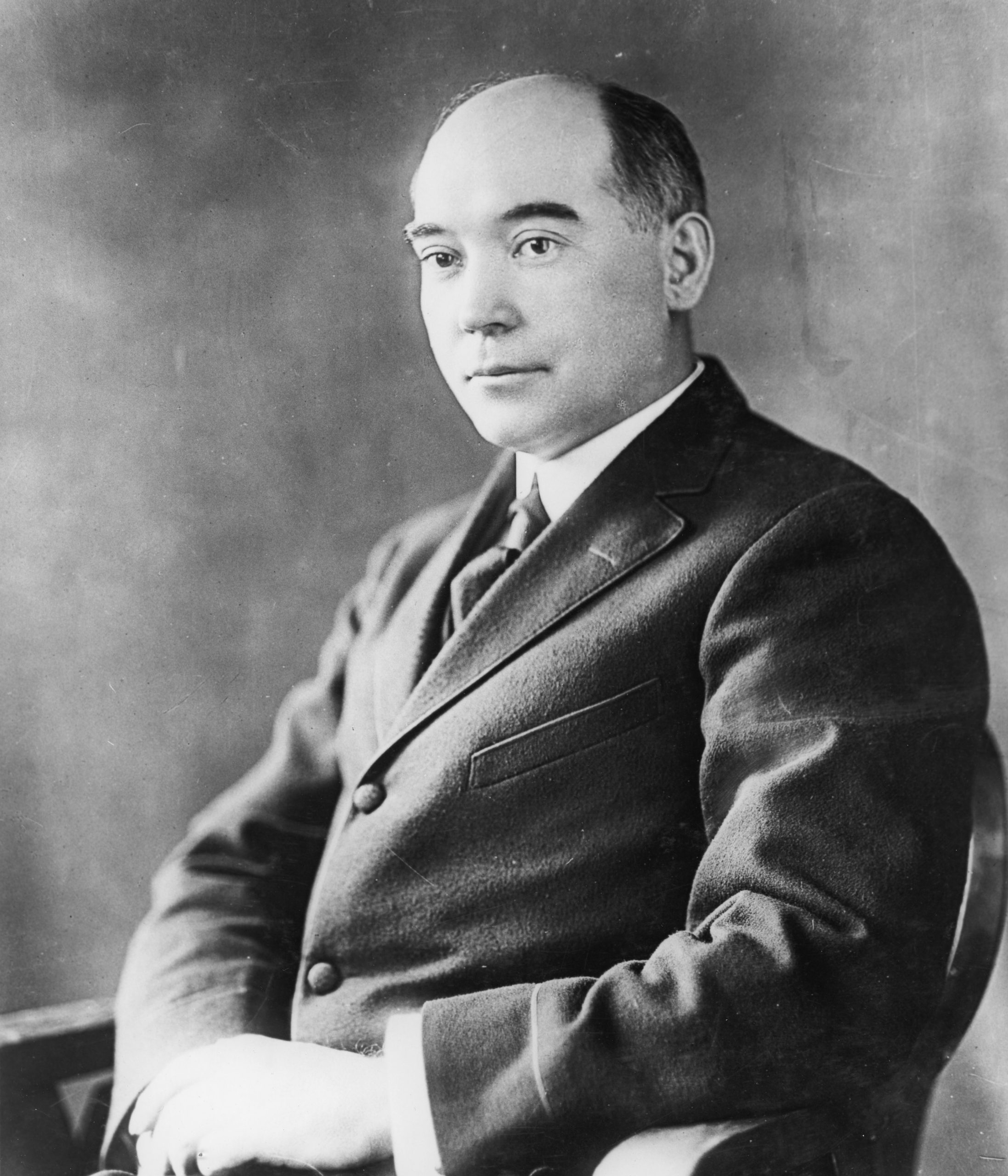

Charles Christopher Mierow took over in 1934 as a permanent department chair. Vernon had been crucial in inaugurating the study of biography on campus. Mierow, by the sheer force of his energy and enthusiasm, presided over a second golden age.

A new faculty member with a silver mane and a kind face, Mierow had never before taught biography. He had previously been the president of Colorado College, where he taught classical and medieval languages and published on the lives of the early Roman emperors. As a result, he felt no inhibition in introducing new courses at Carleton, including “Representative Modern Europeans,” which took up the lives of Cervantes, Frederick the Great, Goethe, Beethoven, Marie Antoinette (a woman at last!), Pasteur, and Ibsen.

MIEROW UNDERSTOOD THE ORIGINS of his modest department, and he respected them. He said he knew of no other field of study whose classroom discussions inspired so much independent reading among students, and he maintained that many of Carleton’s best and brightest were taking his classes. He eloquently wrote of biography’s status as a field independent of history. “It has been said that all history is important only because it happens to human beings; its processes ‘clothe themselves in human lives,’ ” Mierow wrote. “It is biography that lights up the past and the present.”

Since its beginnings, the department had discouraged students from declaring a biography major. Mierow recognized the difficulties students would face in continuing their studies, since no American graduate school offered a program in biography, yet he acceded to the request of Patricia Odell ’38 to major in biography. Noël Phillips ’40 soon followed.

In 1943 Vernon—who had taught biography at Dartmouth until 1932, and with whom Mierow frequently corresponded—informed Mierow that Dartmouth had temporarily suspended its biography department, leaving Carleton once again with the academic world’s only such center of study.

Interest peaked in 1948–49, when an impressive 429 people enrolled, and the department flourished as a tiny jewel that adorned Carleton’s liberal arts curriculum. “I am surprised that so few colleges seem to realize this,” Mierow observed.

Mierow retired from the faculty in 1953 and, since few scholars were interested in teaching the college’s six-course biography curriculum, the Department of Biography retired with him. Mierow’s tally showed that his courses had 4,910 enrollments over 19 years, not counting the earlier courses taught by Vernon and Wedel. In total, six Carleton students majored in biography.

Vernon died suddenly in 1951 at age 80 while playing bridge at his home in Hanover, New Hampshire. Before his death, he donated 6,000 biographical texts to the Carleton library and gave $75,000 to the college to endow a fund to support the teaching of biography.

Mierow died in 1961. At Dartmouth, the biography department reopened at the end of World War II but permanently closed in 1967.

I could have learned an important principle from Mierow and the colleagues who preceded him: Biographies can be more than a project, a book, or a single life. Between foreground and background, they can contain a world. I will remember that the next time I start writing about someone’s life.