Most of us remember our parents admonishing us to “go play outside!” Today, as technology threatens to overwhelm us, we would do well to turn off our electronic devices and embrace the outdoors.

Since Henry David Thoreau built a shack on Walden Pond to “live deliberately,” Americans have come to believe that nature is good for us. This positive view of nature springs from late 18th and early 19th-century romanticism. Michael Kowalewski, Carleton’s McBride Professor of English and Environmental Studies, traces a literary line from Thoreau, the transcendentalist who saw in nature the reflection of spirituality, to writer and adventurer John Muir, who proclaimed a temple of America’s remaining wilderness through, in Kowalewski’s words, the “celebratory rhetoric of the sublime.”

The line passes through writer and scientist Aldo Leopold, who found nature in the restoration of broken-down Wisconsin farmland and declared, “There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace.” Then to author Wallace Stegner, to whom we owe the notion that the value of wilderness lies in our knowledge that it exists—even if we do no more than tiptoe to its edge once in awhile to peer inside.

In nature we found a source of health, of identity to distinguish us from wilderness-poor Europe, of scientific knowledge, of personal character, and of spiritual awareness. Kowalewski, who teaches American nature writing, says these themes still resonate today—especially Muir’s exuberance. “The students love his open embrace of nature—the whole idea of climbing a tree in a storm and swaying back and forth, and feeling the sheer kinetic power of that,” he says. “It’s very heartening to me that students are still inspired by Muir.”

Our literary celebration of nature was the flip side of our fear that wild spaces—the frontier of 19th-century America—were vanishing against a backdrop of furious land clearing and settlement, says George Vrtis, associate professor of environmental studies and history at Carleton.

In 1790, according to the nation’s first census, nearly 95 percent of the nation’s population lived on farms or elsewhere in the “country.” Ever since, Americans have been migrating to the cities. By 1920, half of us lived in urban areas. By the 2010 census, more than 80 percent of Americans lived in cities and suburbs. Urbanization and industrialization were the “two major engines of change,” says Vrtis. As farmers became more productive, rural jobs and livelihoods disappeared. At the same time, city factories were hiring. So,

says Vrtis, the “rural population of the country shrank dramatically as the demands of the labor force shifted.”

Think of the impact today. If you’re a Midwestern baby boomer, you may have visited relatives on the farm. But if you’re of college age, chances are the only farm you’ve visited was on a field trip. As a result, the once-common nature-related experiences of caring for domestic animals and crops or hunting the back 40 have largely disappeared.

Likewise, jobs performed in the woods and fields and on the highways and byways are changing or disappearing. “The workaday world of people doesn’t often involve nature,” says Vrtis. Missing is the “day-to-day experience, that visceral contact—a good deal of that was lost as the nation grew more urban and industrialized,” he says. “Most of our interaction with nature today is for play. We go for hikes. We go for recreation. That’s a different way of knowing nature.”

Moreover, people of all ages are spending more time looking down at their tablets and smartphones than out to the world around them. Even when they take a hike or run in a nearby park, their iPods provide the soundtrack—not nature.

“Our experience with nature is becoming increasingly mediated by technology,” says Matthew Pelikan ’80, restoration ecologist for the Nature Conservancy on Martha’s Vineyard. “Watching animal videos on Facebook instead of experiencing things firsthand is probably better than ignoring the natural world completely, but you lose a lot of nuance when you’re not out there engaging all of your senses. I think the risk is that people simply aren’t going to possess real knowledge of the natural world, and gain insight into how to protect it.”

Like many people with an intense love for the outdoors, Pelikan discovered his as a child. “When I was 18 months old, my mother wrote in my baby book—and I can imagine her disappointment—that I preferred animals to people,” says Pelikan. “It’s only gotten worse since then.”

On Martha’s Vineyard, Pelikan and the Conservancy protect natural areas from development by acquiring land and conservation easements or managing important habitat. On a shellfish restoration project in one of the Vineyard’s salt ponds, Pelikan works with shellfish fishermen. “These are guys who spend a lot of time on the water,” he says. “They have a profound understanding of how things work in the ponds and bays around the island. There’s a strong tradition of hunting and fishing and gathering food from the wild, which makes conservation efforts relatively easy to do. People here have a firm grasp on why the natural world matters.”

Pelikan also works to educate a summer population of urban vacationers. “They love the place but they don’t really understand it,” he says. “They bring a suburban ethos with them and they want their house and yard to look like the traditional American house and yard.” As a result, homeowners might plant unwelcome exotics such as Asiatic bittersweet or overdose their lawns with fertilizer, which runs into nearby waterways. “Trying to persuade people that their lawn doesn’t have to be—and really shouldn’t be—emerald green can be difficult,” says Pelikan. “It’s rewarding when they say, ‘I never thought of it that way.’ ”

Massachusetts author, educator, and artist Clare Walker Leslie ’68 finds a wide range of attitudes toward nature as she teaches nature journaling and field drawing across the country. Leslie introduces people of all ages and interests to nature through her books and workshops. “Recording what they see in the field is how many explorers and scientists verify their observations,” she says. “I tell my students: ‘It’s important to observe and to pay attention. To do that you have to slow down and watch the fascinating world around you.’ And now I enjoy doing this with my two-year-old granddaughter.”

In September Leslie taught field observation and drawing to residents of a village community in rural Alaska. She was impressed by their ability to embrace both the beauty and harshness of their landscape. “Last spring, most of their town was flooded by the Yukon River. As a result, they

have a fresh awe and respect for nature. Yet in the midst of rebuilding, they would stop to look at sunsets and appreciate their surroundings.”

Over the 40 years that Leslie has been teaching, she has observed the change that comes over people, as well as herself, when engaged in an outdoor pursuit or activity. “Whether it be hiking, gardening, birdwatching, or drawing and observing nature directly, people seem happier, calmer, and more connected to where they are.”

Over the 40 years that Leslie has been teaching, she has observed the change that comes over people, as well as herself, when engaged in an outdoor pursuit or activity. “Whether it be hiking, gardening, birdwatching, or drawing and observing nature directly, people seem happier, calmer, and more connected to where they are.”

In fact, the perception that spending time outdoors makes people happier and healthier has scientific backing, as researchers are finding ways to measure and document the benefits of being out in nature. A number of studies suggest that nature helps increase attention, reduce stress, lower blood pressure, and even foster creativity.

University of Michigan researchers found that strolling through a park, compared with walking in a city, improved test results for attention and recall. Likewise, Japanese researchers show that when compared with city walks, forest walks are more likely to reduce blood pressure, heart rate, and the level of the stress hormone cortisol. Finnish researchers found that teenagers who live on farms or in the woods have stronger immune systems and fewer allergies than kids who live in the city. Author Richard Louv, who coined the term “nature deficit disorder,” reports that time in nature calms children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. A 2011 study found that adults improved their results on a creative, problem-solving task by 50 percent after completing a four-day Outward Bound wilderness trip.

Such benefits have even been found to accrue. Move closer to green space and your mental health improves immediately and sustains for at least three years, according to a recent study in the journal of Environmental Science & Technology.

These findings are no surprise to Heather (Ristow) Bilden ’00, education director at the Audubon Conservation Education Center in Billings, Montana. Teachers find that even their most disruptive students are transformed out here, says Bilden. “We can get through to kids who are not being reached at school. When kids are outside collecting and identifying insects, their faces come alive with the discoveries they make. It’s healthy for their little bodies to be moving around outdoors while their brains are making connections. They have vivid memories of these experiences.”

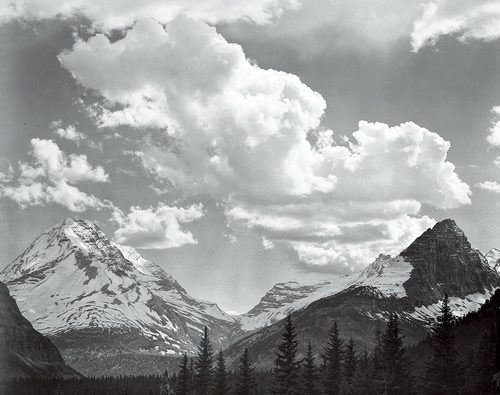

If any landscape retains the essence of John Muir’s idealized wilderness, it is the national park system, often called America’s best idea. “The landscapes here are so powerful that they make peoples’ jaws drop,” says Jeff Mow ’81, superintendent of Glacier National Park, one of the system’s crown jewels. “Visiting the national parks is another way for people to make emotional connections to the landscape.”

Yet even remote, rugged Glacier, with its grizzly bears and rustic log-and-stone hotels, is struggling to attract new visitors. “We have hotels that are 100 years old,” says Mow. “They don’t have TV. They don’t have Internet. They advertise the fact that you’re going to experience Glacier like you did in the 20th century.

“But we’re not sure that experience appeals to today’s youth. They want to take a picture of a spectacular view and text it to friends or post it on Instagram. That’s something the National Park Service hasn’t been able to come to grips with. What kind of experiences do we want them to have? What kind of connections do we want visitors to make with the landscape?”

Moreover, visitors to national parks—typically white and middle class—are not representative of the changing U.S. population. As a result, the Park Service has begun targeting new visitors by promoting such historic, urban parks as the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, and the Boston Harbor Islands.

“I like to think of these places as gateways to nature,” says Mow. “If we can ensure that people feel welcome by the National Park Service in those urban areas, then perhaps they will feel comfortable exploring a park in a completely unfamiliar area.”

Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell stresses the importance of engaging the next generation in understanding and stewarding our public lands. As she noted in remarks to the National Press Club last October, “The Millennial Generation—now young adults aged 18 to 33—is larger, more urban, and more diverse than any generation in our history. Research shows that this generation cares about the planet and wants to make a difference in their careers, yet they have grown up more disconnected from the natural world than ever before. Already outnumbering the boomers by 3 million, these individuals will soon be our nation’s elected officials, business leaders, parents, and public servants. But what happens when a generation who has little connection to our nation’s public lands is suddenly in charge of taking care of them? . . . For the health of our economy and our public lands, it’s critical that we work now to establish meaningful and deep connections between young people—from every background and every community—and the great outdoors.”

Scientist and author E. O. Wilson popularized the term biophilia to describe his hypothesis that human beings have an instinctive urge to affiliate with other forms of life. And of all the forms of life, none exert a stronger tug than large mammals. No one knows that better than Peggy Callahan ’84, who directs the Wildlife Science Center near Forest Lake, Minnesota. Some 20,000 schoolkids visit the center each year. “No child left indoors is our motto,” says Callahan.

Scientist and author E. O. Wilson popularized the term biophilia to describe his hypothesis that human beings have an instinctive urge to affiliate with other forms of life. And of all the forms of life, none exert a stronger tug than large mammals. No one knows that better than Peggy Callahan ’84, who directs the Wildlife Science Center near Forest Lake, Minnesota. Some 20,000 schoolkids visit the center each year. “No child left indoors is our motto,” says Callahan.

The draw? The nonprofit center’s research animals—primarily wolves, but also mountain lions, bobcats, and bears. “If you can get kids excited about a living thing and combine it with the outdoors—you’ve got their attention,” she says.

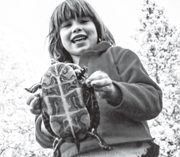

True, not all science or nature facilities can offer wolves and cougars, but many have snakes, turtles, or other living creatures to capture a visitor’s attention, and plenty of space and activities to occupy youngsters. “We sneak education into some fun packages,” says Callahan. “Taking advantage of these programs is one of the easiest ways to get your kids excited about going outdoors.”

Ultimately, most nature lovers hope to inspire others to love and appreciate nature as much as they do. “I like the fact that when people fall in love with the outdoors, they find a way to learn more about it,” says Callahan, “which naturally leads to ‘Hey, we have to take care of this or it’s going to go away.’ ”

Greg Breining is a freelance writer based in St. Paul.