Carls are working to serve both local and international communities in a time of need. We interviewed a cross-section to learn more about their contributions.

Chris Purdy ’88

Robins and cardinals, cooing love songs, routinely serenade Chris Purdy in his screen porch, which doubles as a home office. The amorous ambience is fitting: Purdy is president of DKT International, one of the world’s largest providers of family planning and contraception. (The nonprofit, founded in 1989, annually distributes 800 million condoms and 100 million oral contraceptives in 90 nations.)

The birds are a reminder of life before the pandemic, and of the day when couples will once again court without risking their health. In the meantime, though, men and women who are quarantined or locked down at home can’t go out to pick up contraceptives. And even if they could, what’s needed often isn’t available due to global supply-chain disruptions. “When this thing first hit, we had sleepless nights and a lot of worry, and we were in a mad sprint,” recalls Purdy, who says a tsunami of inventory shortages and multimillion-dollar cash-flow woes hit DKT. “Now we’ve slowed that sprint to a steady clip. We know it’s a marathon.”

Over the past few months, more than 7 million unintended pregnancies were reported, according to the United Nations Population Fund. “There’s no way to recover the two to three months that were lost when someone didn’t take pills,” says Purdy, predicting that there will be “a little baby-boom blip” in six to nine months.

As DKT works through the crisis, Purdy is confident that changes being made out of necessity will lead to lasting reform, in large part because family planning organizations are having to sharpen their online services, including improving the navigability of databases and taking advantage of advances in artificial intelligence.

One result has been increased access to TelAbortion: a woman meets with a doctor over the phone or on the internet and, assuming it’s deemed a healthy approach, is prescribed a drug (sent in the mail) to safely terminate her pregnancy. “There are a lot of eyes on us, because if we can do it right, this has the potential to change the landscape in a lot of other places as well,” Purdy says. (George Spencer)

Erin Anderson ’12

They live on violent streets and in cramped migrant camps. In Mexican border towns—since the U.S. government’s Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) were enacted in January 2019—nearly 60,000 migrants seeking asylum in the United States have waited months for court dates. Thousands not designated for MPP who cross the border are imprisoned without charge in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centers. Most are held for months, sometimes years, until they’re granted restricted release or deported. Some are let go on a bond that averages $8,000 but can go as high as $15,000. Both amounts are too high for many to pay.

In overcrowded conditions on both sides, people have long shared too few toilets and lacked basic supplies, nutritious food, and decent health care. The coronavirus and the need for social distancing, which is all but impossible, has made things even more inhumane.

“We haven’t seen anything this egregious in the contemporary history of U.S. immigration,” says Erin Anderson. A fully accredited representative of the Department of Justice, she practices immigration law as a licensed attorney would.

As a pro bono coordinator with Al Otro Lado—a Southern California–based legal services organization defending the rights of indigent deportees, migrants, and refugees—Anderson focuses on legal representation for MPP-designated and ICE-detained migrants. Since before the coronavirus struck, she and volunteers have prepared countless requests to release ICE detainees; now they are basing requests on people’s susceptibility to COVID-19.

“All but a tiny fraction have been denied,” she says. “Detained migrants are dying from COVID-19, but even the coronavirus isn’t enough to make people care about immigrants’ lives. Few recognize this as a formal refugee crisis, so basic standards don’t have to be met.”

The solution? Al Otro Lado is calling for migrants’ immediate release and the closure of all ICE detention centers. “Don’t we want to be a country that’s generous and welcomes migrants?” Anderson asks rhetorically. “No one leaves their home country unless they feel they have no other choice.” (Claire Sykes)

Brianna Engelson ’13

One of the few things that can keep pace with a deadly virus is human caring.

In early March, when the University of Minnesota’s medical school canceled in-person classes, Brianna Engelson and a dozen of her fourth-year peers suddenly found themselves separated from their mentors and patients—“anyone who gave us meaning in our lives,” she recalls.

After seeing a tweet that listed ways people could help during the crisis, the caregivers-in-training exchanged a flurry of texts and emails. “We all had a laser focus on a common goal. That’s how badly we wanted to give back to our community,” Engelson says. A plan was hatched to launch MN COVIDsitters, a volunteer effort to match students with local health care workers in need of child care, pet sitters, or someone to pick up groceries or prescriptions, or run other errands.

After the idea was posted on Facebook, 125 volunteers appeared overnight. Next came a website (mncovidsitters.org). Then a local company created an app to match helpers with workers. “Soon we had all these motivated people working their butts off,” says Engelson, who is now in the university’s psychiatry residency program.

By late June, MN COVIDsitters had provided babysitters for more than 250 Minnesotans, and the effort had grown to include 50 medical schools in 21 states and four more countries. Only college students can volunteer, which helps ensure that all involved have up-to-date vaccinations and have passed a basic background check. To stifle the virus’s spread, a volunteer is assigned to just one family.

Engelson handed the leadership reins to younger students in June. “A lot of people feel helpless, given the magnitude of everything that’s been going on,” she says. “One of the best things we can do is remain connected, check in on each other, and find something that gives us purpose.” (Spencer)

Chris Courneen ’07

With a Carleton degree in Black cultural identities and dance, Chris Courneen currently works as the senior director of human resources for MS International, a leading importer and distributor of natural stones, countertops, landscaping tiles, and porcelain in North America.

When COVID-19 hit, Courneen and his company began facilitating the shipment of masks from China to the United States, as well as the distribution of technology and meals to people in need. They’ve been able to leverage their strong and deep relationships with vendors around the world, and particularly in China, to facilitate the shipment of tens of thousands of hospital masks and KN95 masks to medical facilities, first responders, and long-term care facilities both in California and around the country.

MSI also started providing iPads and Chromebooks to families and schools in the U.S. They have donated over 1,000 iPads and Chromebooks to individual families and hundreds to local schools to support virtual learning. The company has also donated over 10,000 meals for first responders and vulnerable populations in Southern California, and have worked to distribute more than 20,000 food relief kits to low-income families in India and hundreds of survival kids to migrant workers, women, and at-risk children living in remote Indian villages.

Courneen’s role in these philanthropic efforts has been “managing everything related to mask distribution,” and his employees have been packing and shipping the masks in a Human Resources conference room. Courneen has also helped organize the distribution of technology for virtual learning.

The manager of the company’s health care benefits, Courneen says COVID-19 “changed the way I think about healthcare and access to healthcare options,” leading to an understanding that “preventative healthcare is really important.” (Lea Winston ’22)

Gretchen Gasterland-Gustafsson ’89

Carleton studio arts graduate Gretchen Gasterland-Gustafsson has been sewing masks in her house in St. Paul from scraps of cotton and yards of elastic. And she’s distributed the masks, as well as some surgical hats, “to anyone who has requested them, as well as local hospitals.”

A professor in the liberal arts department at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and the head of costume design at Out on a Limb Theater Company and School, Gasterland-Gustafsson is an experienced seamstress and had plenty of materials she could put to use, “so the idea of making masks came pretty quickly.”

“Lack of available masks for the general population was already on my mind,” says Gasterland-Gustafsson, who is currently hosting two Chinese international students in her home, one of whom was working to send PPE to Wuhan before the outbreak began in the United States.

“Honestly, I needed an outlet for my frustration at the lack of preparedness we are seeing, and sewing made me feel like I could do something to help,” Gasterland-Gustafsson says. “I would like to believe that I have done the little I can to help slow the spread of the contagion.” (Winston)

Claire Du ’08

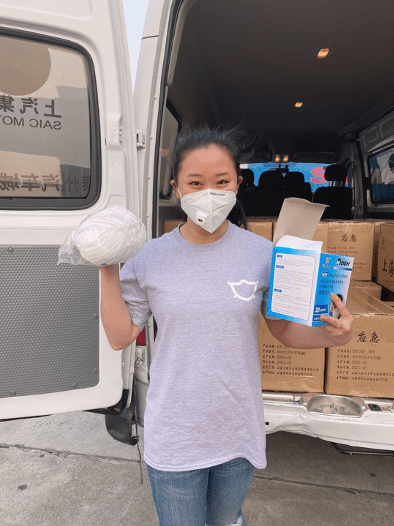

After graduating from Carleton with degrees in history and political science, Du eventually moved back to China to work as an impact investor in the field of education. Du is now an advisor for Owl Ventures, the largest venture capital fund in the world, as well as one of the founders of Operation Masks, a nonprofit helping ship masks from China to the United States.

Du lived through the coronavirus pandemic in China long before it became a national crisis in the United States. On January. 22, Du returned to her hometown of Changsha, 200 miles from Wuhan. The next day China went into lockdown, and Du spent the next nine weeks in quarantine with her family. “A lot of my family friends got infected,” she says, remembering that at least 13 of her mother’s family friends perished. “It was a pretty scary time.”

When China was in the thick of the pandemic in late February and early March, Du first became involved with relief efforts by launching a t-shirt project called #LoveUnity with Phillip Lim, the famous Chinese-American designer, and friends in Hollywood and China. “The idea was that during COVID-19 there shouldn’t be any discrimination against Asian and Chinese [culture], and that this whole thing is supposed to be a unified fight against the virus rather than a fight against race or nationality,” Du explains.

As the situation grew worse in the United States, Du began to source mask manufactures and other personal protective equipment (PPE) companies and put together a Google Sheet to share on Facebook with family and friends. She then teamed up with investors and entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley and China to form Operation Masks, a nonprofit to “help government and hospitals in the U.S. to get direct access to factories in China at cost.”

The first week of May, Operation Masks shipped 3 million masks from China to the United States. They were one of the few suppliers for the United States that could get the highest-level NIOSH-N95 mask. In the month of May alone, Du expected to ship around 1.5 million NIOSH-N95 masks, 1 million surgical gowns, and 2 million surgical masks to the United States. The nonprofit has also worked to help corporations obtain non-surgical masks for everyday use.

“I think we are one of the largest platforms now between China and the United States on PPE supplies,” Du says. Operation Masks has survived longer than other similar projects because Du’s deep connections in China allows them to access the Chinese factories.

Du has been spending 18 hours a day running the China team’s activities managing factory relations and accessing the PPE. “It always makes me feel very good that I’m making a contribution to the world,” she says. “We want to be as helpful as possible.

“This whole work has been a combination of investment banking, consulting, operation management, supply chain management, international relations, public relations, government relations, customer relations, logistics, data analytics . . . Thanks to my liberal arts education at Carleton, I was equipped with all that.”

Moving forward, Du expects to return her focus to her work with Owl Ventures and transition from a hands-on role to a supervising role within Operation Masks. (Winston)

Chris Martin ’00

Talking with Chris Martin, one can’t help but think of The Miracle Worker, in which teacher Anne Sullivan uses a pump handle to teach a deaf and blind Helen Keller her first word: water. A modern-day version of the film’s protagonist, Martin uses poetry and iPads to get language flowing from the minds of nonspeaking autistic teens and adults.

“They type amazing, fluent English,” says Martin, cofounder and executive director of Unrestricted Interest, which works with students at the South Education Center, a special education school in Richfield, Minnesota. Since the coronavirus emerged, he and his team of teachers, all of whom are poets, have been working with a growing number of students around the United States via distance learning. For many of these students,” says Martin, “their poetic voice is their voice. Period. That’s revolutionary.”

People with autism have sensory motor dysfunctions that prevent them from organizing how their tongues, throats, and fingers work, and that renders them unable to speak, according to Martin, who has taught “American Lyric: Poetry, Pop, and Rap” at Carleton. “The real tragedy,” he explains, “is that when you have a miraculous emergence, it doesn’t mean the person’s language ability just started. It was there the whole time.”

When Martin met Meghana Junnuru three years ago, she was 19 and communicated only by using icons on her iPad to convey simple concepts such as drink and bathroom. He had a hunch that a reservoir of creative potential was just waiting to be unleashed.

Martin asked Junnuru to write a poem in which each line explored a difference sense. When they came to the line about taste, Martin says, “she got so excited she started jumping up and down on the yoga ball she was using as a chair and was kind of screaming a little.” While he was trying to figure out what she was doing on her iPad, she typed c-o-r-i-a-n-d-e-r to complete the line “Awe arrives as a taste of coriander.” Junnuru later told Martin this liberating moment “felt like thunder and lightning in her brain at once.” She has since started a nonprofit called the Autism Sibs Universe that will soon open Minnesota’s first neurodiversity-focused cohousing community.

The lockdown has hastened the development of many more students like Junnuru who, according to Martin, have had the rare chance “to reawaken their senses to the natural world and their bodies.”

“COVID created an incredible opportunity for them to remember what it’s like to walk around every day. These students have so much wisdom. They’ve thought through this so much they can be leaders now.” (Spencer)

Sarah Hagerty ’13

After majoring in psychology at Carleton, Hagerty is now in her last year of a dual PhD program in clinical psychology and neuroscience, splitting her time between research at Stanford and a residency at VA Hospital in Palo Alto providing clinical care for veterans.

The COVID-19 pandemic inspired Hagerty to think “about how to use the things I’m already doing to apply them to COVID,” leading to her work developing research studies around coronavirus and publishing articles about how to stay mentally healthy during quarantine.

“It almost felt like a responsibility that I have to my liberal arts training and to everything that I’ve done so far to use that perspective to effect positive change in a timely way,” Hagerty says. “For right now, it seems most important to characterize the scope of the mental health impact of COVID and also to use our research skills to provide insights immediately about what could be done right now to mitigate some of the negative impact that COVID is having on our mental health.”

To that end, Hagerty is working on designing research studies about the impact of coronavirus, which are soon going into the field. One study is about the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers, which could lead to post-traumatic stress disorder. “There are some interesting parallels between what the healthcare workers are facing right now treating coronavirus patients and what we notice about veterans coming back from combat areas,” she says.

In addition to research, Hagerty has been writing articles about how to reduce stress while in quarantine, such as this op-ed published in the San Francisco Chronicle. Through her writing, Hagerty hopes the “public can understand what their current experience is like from a psychology framework” and to offer “some tidbits of information about how people can modify their habits in even very small ways to improve their mental health and stay connected to one another.”

“I’ve noticed a new sense of feeling energized and feeling fulfilled when my work is really contributing to something very applied and very timely,” Hagerty concludes. “I’d like to continue to find ways to integrate the broader current events and things going on and making my work as applied as possible because I think it has led to more fulfillment.” (Winston)

John Fangman ’88

John Fangman is a practicing infectious disease doctor and senior hospital administrator at a hospital in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. After receiving a degree in political science from Carleton, Fangman earned his medical degree from the University of Minnesota.

As Fangman was driving to work one day in March, at the start of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States, the song “Save it for Later” by the English Beat came on the radio, reminding Fangman of his years at Carleton. “It catapulted me back, and I thought I would love to talk about what we are going through with a bunch of Carleton people,” he says.

Fangman contacted his friends from Carleton who helped him organize a webinar for his class of 1988 to discuss COVID-19. On the call, Fangman presented to some 30 classmates on how the novel coronavirus was developing in the United States and how it was projected to continue. Afterward, there was a Q&A session for people to ask questions and have an open-ended discussion.

As a political science major turned doctor, Fangman says he’s “always lived in this interface between healthcare and policy,” leading to his observation that “the real problems that COVID-19 reveal are about how we organize society and the world.” At the end of the pandemic, Fangman hopes we will understand that “there are basic standards that we all have to live by because otherwise we all suffer collectively.”

In his Milwaukee hospital, Fangman says they have been “preparing for the worst and planning to live with this for the next 12-18 months.” Like most hospitals around the country, at Fangman’s institution they have cut back on elective care, causing him to see “a number of patients that came in much sicker than they normally would have been because they differed getting care.”

At the end of the day, Fangman does not see his work as a healthcare worker as an act of bravery. “When you’re a doctor, you just be a doctor,” he says. “People like me, infectious disease doctors, this is what you live for.” (Winston)

Andrew Garrett ’90

Andy Garrett says he’s spent his entire career “focused on public service, emergency response, and emergency management,” all of which are imperative when responding to a global pandemic.

Garrett currently holds a split position as faculty and program director for George Washington University School of Medicine’s emergency health services and as a senior advisor with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR). Both of these positions have put Garrett in the middle of deliberations and conversations around the coronavirus pandemic.

At George Washington University, Garrett is a member of the Pandemic Task Force, and explained that he helps “keep the senior leadership informed of the latest science around COVID to help guide our response to the pandemic.” Within that group, Garrett is one of the doctors in the Intelligence Cell, which he explains “monitors the growing evidence base around COVID to help inform the senior leadership and steer important operational decisions for the University, such as when to resume on-campus education.”

In his role at HHS ASPR, Garrett worked in the field on the first major federal quarantine in 60 years, caring for hundreds of people from a cruise ship. “Patients required medical evaluation and ongoing screening and care for two weeks while they stayed in a facility on a military base,” Garrett says. He is also “working directly on national-level operational issues related to COVID and children, and helping ensure that our national disaster medical response workforce through the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS) is optimized.”

Finally, Garrett works several shifts per month in a pediatric emergency department in Washington, D.C.

“Carleton is where my initial interest in emergency services came together,” says Garrett, who organized Carleton’s first on-campus EMT classes in 1987 and worked with Northfield Ambulance as an Advanced EMT during his four years.

“Carleton gave me the flexibility to pursue these types of outside interests, and I was fortunate to have amazing advisors like professor Ed Buchwald who encouraged me to take risks and mash up my areas of interest in different ways. That approach teed me up for a fascinating career in medicine and public health that never would have happened if I had taken a traditional approach to pursuing a career in medicine.”

Through his years working for the federal government, Garrett has responded to “dozens of major disasters” such as Hurricane Katrina and the Haiti earthquake. “I keep going back because in every disaster, COVID included, there is incredible potential to do the right thing and help those who need it most,” Garrett says. “So, while maybe COVID hasn’t changed me as a person, per se, it has reinforced my desire to be part of the national solution to one of the most significant public health challenges we have faced in a century.” (Winston)