Dan Dougherty ’49 recalls the day he and his fellow American soldiers liberated the Dachau concentration camp.

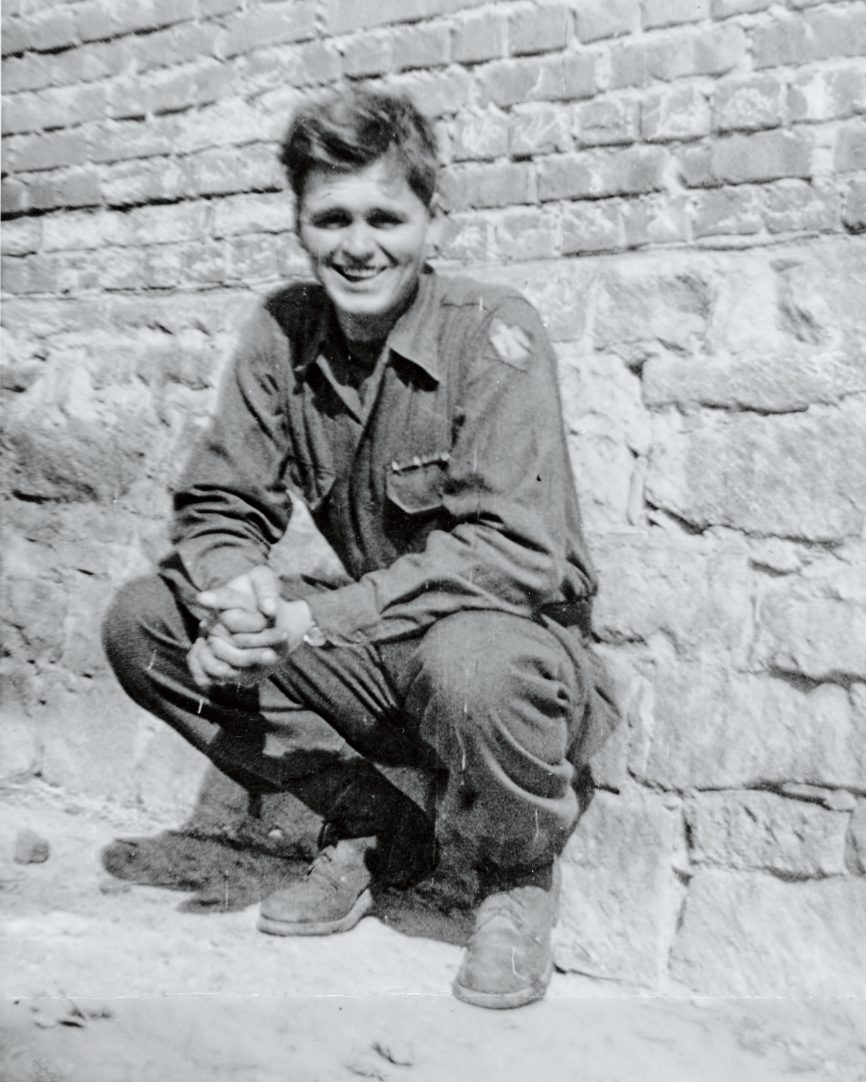

Seventy-five years after the U.S. Army’s 45th Infantry Division came upon an idle train in the German countryside, the memory hangs graphically in the mind’s eye of Dan Dougherty ’49.

“We were used to death and destruction,” he says of his World War II experiences in Europe, “but nobody gets used to walking up to 39 boxcars full of corpses.”

On April 29, 1945, the division’s C Company, with Dougherty as its platoon guide, was following orders to sniff out remaining Nazi guards at the Dachau concentration camp. At the time, the soldiers were unaware of what had been happening at the complex. The company arrived after an hour-long march from the outskirts of Munich to find the boxcars on tracks just outside the camp gates.

In what would come to be called the “death train,” soldiers found the emaciated bodies of 2,310 prisoners, who, while they were alive, were being transferred to Dachau from the Buchenwald camp in the waning days of the war. Most of the prisoners died en route from exposure, malnutrition, and dehydration.

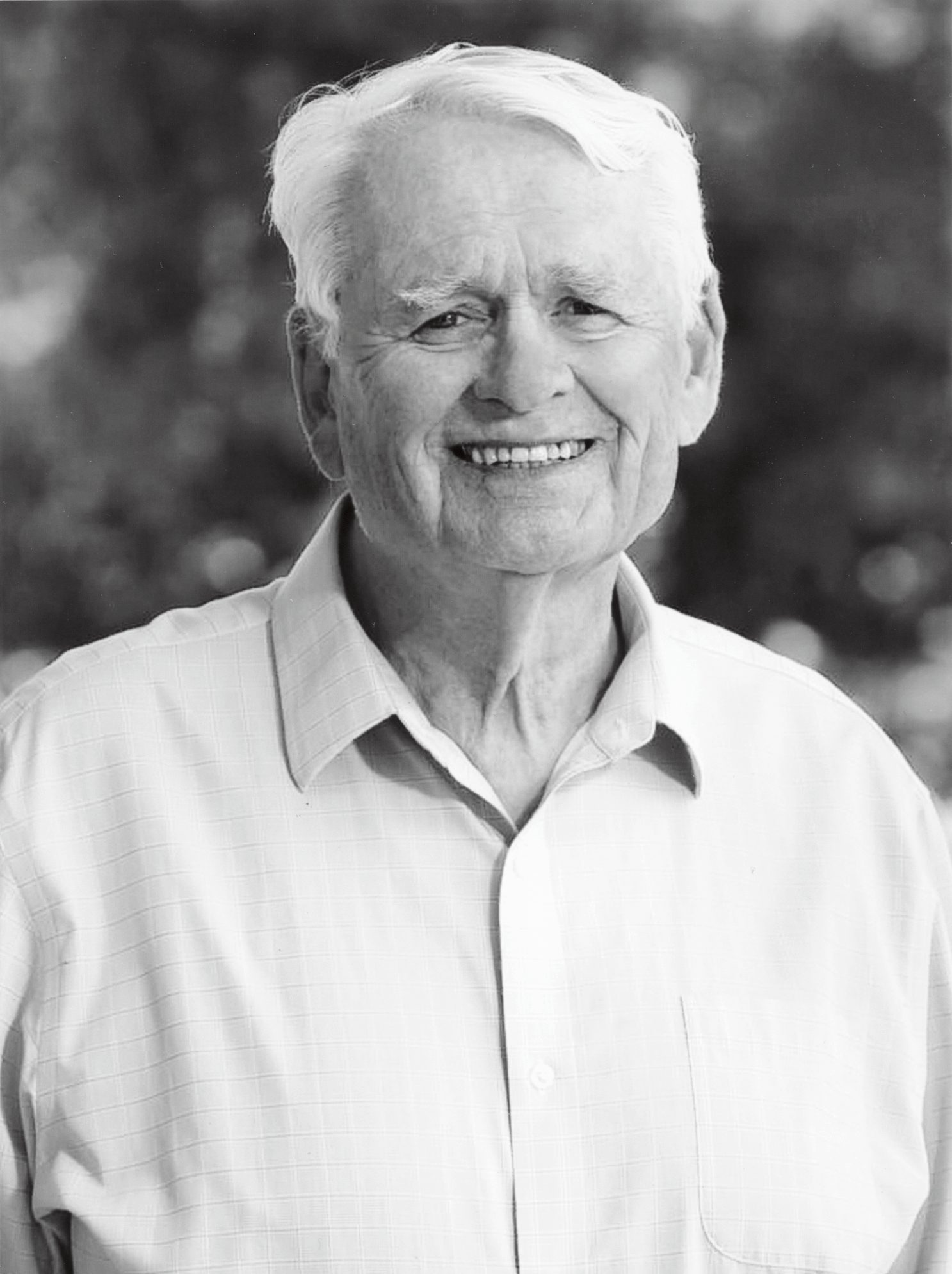

At 95, Dougherty is one of only two surviving members of the 45th Infantry Division. He planned to fly to Germany in May to take part in events honoring the camp’s liberation, but COVID-19 forced ceremonies to be canceled. Instead, he was interviewed by a German production company for a documentary about the Allach concentration camp, a Dachau satellite camp that was created to produce items for Germany’s porcelain market.

The barbarity of that spring day at Dachau left an indelible impression on Dougherty. In the 1990s he wrote a memoir, C Company at Dachau, about his experiences in the war. Describing himself as a “minor actor in history,” Dougherty says he has since read countless books on Nazi Germany and its atrocities.

“I’ve had a great interest in trying to understand how the Germans, arguably the most educated people in the world at that time, could produce and sustain the Third Reich,” says Dougherty, who lives in Fairfield, California. “I’m not sure we know the answer to that yet, although a lot of people have attempted to find it.”

The Nazis opened Dachau, their first concentration camp, in 1933 initially to house political prisoners. Before the camp was liberated in 1945, 41,500 people had died there, including targeted groups such as Poles, Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Catholic priests, gay people, communists, and members of the Romani ethnic group.

United States service members freed more than 31,000 prisoners that day. Most of the prisoners stayed inside the barracks while the soldiers scoured the grounds for members of the Schutzstaffel—the SS—the paramilitary organization that carried out most of the concentration camp killings. (After the war, Dachau was used to hold SS members who were awaiting trial.) Dougherty toted a Thompson submachine gun, but was ordered to keep all witnesses alive.

After coming upon thousands of corpses, however, some of the soldiers “had a hard time handling their emotions,” says Dougherty. “In the course of rounding up several hundred SS guards, there was a breakdown in discipline—officers and GIs alike—and 30 guards were killed without the benefit of a trial.” Following an investigation into the incident, no charges were filed against any American soldiers.

Dougherty and his men found the bodies of 17 SS guards in Dachau’s coal yard. A corporal cut off a finger from one of the bodies to retrieve an SS ring as a souvenir. A reporter remonstrated with the soldier, “but the deed was done,” Dougherty recalls.

Until that day, the soldiers hadn’t heard of the concentration camps, says Dougherty, and it wasn’t immediately clear to them why there were two thousand dead bodies in boxcars. Some of the corpses wore striped uniforms or rags; many were naked. Some soldiers cried, others yelled and cursed, but for most of the men, the grisly tableau had one effect: “We were stunned,” Dougherty says. “It wasn’t until years later that I really learned all about that train.”

The men spent only 13 hours at the camp, sleeping in SS officers’ quarters before returning to Munich before dawn. “We couldn’t get over the contrast between our quarters and the depravity outside,” Dougherty says. “Our home had lovely flower gardens, upholstered furniture, and framed pictures on the wall.”

Dougherty, who served a total of 29 months in the Army, grew up in Austin, Minnesota, and enrolled at Carleton in 1946 on the GI Bill®. After receiving a degree in sociology, he went into social work and then sold insurance for most of his professional life. He and his wife of 69 years, Norma, have three children and seven grandchildren.

In June 2019 he regaled his class’s 70th reunion participants with war stories. (Dougherty received a combat infantry badge, a Bronze Star, and a Purple Heart after being wounded along Germany’s Siegfried Line, the month before Dachau’s liberation.) One of Dougherty’s proudest Carleton moments came while he was playing guard for the basketball team: in a game against Hamline University, he held future NBA Hall of Famer Vern Mikkelsen scoreless. Despite Dougherty’s outstanding play, Hamline routed the Knights 89–20.

Dougherty still fields regular inquiries from German reporters about his role at another time and in another place, and he summons the memories easily. Some experiences are not easily forgotten.