Through her work as a mentor to men behind bars in Minnesota’s prisons, Carleton professor Deborah Appleman shows that teaching is a radical act.

Prisons lie.

They promise safer streets. They whisper to victims that retribution is justice. And they tell their tenants—in word and in deed—that stripping them of their humanity is not only necessary, it’s deserved.

They have to. It’s what prisons are designed to do.

This institutionalized duplicity is a recurring theme in Deborah Appleman’s indispensable book, Words No Bars Can Hold: Literacy Learning in Prison (W. W. Norton & Company, 2019). “The thing that’s so interesting about the carceral state is that most people could go their entire lives without thinking about it,” explains Appleman, who is Carleton’s Hollis L. Caswell Professor of Educational Studies. “That’s why [prisons] are out in the boondocks. Out of sight, out of mind. And the things the public can see from the outside are misleading. The cells—really all the things that make confinement unbearable—are hidden. And the public spaces are normalized to make you think, ‘Well, maybe it’s not that bad.’ But it is that bad.”

Standing in the foyer of the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Faribault, a medium-level campus just 20 minutes south of Northfield, is a case study in this sort of insincere advertising. The guards ushering Appleman and five other visitors from the Twin Cities through an early-evening security check couldn’t be nicer. Unlike the icy, rutted roads running through the town of 24,000, the walkways between the gatehouse and a series of educational buildings are well shoveled and lit. The nondescript detention blocks, housing some 2,000 men, recede in the darkness, no more menacing than a suburban office complex. Even the towering chain link fences, ubiquitous and topped with coiled barbed-wire, barely register as you stroll the unpopulated, near-noiseless grounds.

The six of us have gathered to attend a joint reading by 16 incarcerated men who’ve just finished one of two multiweek classes sponsored by the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop (MPWW): Speculative Fiction, taught by Minnesota-based author Abbey Mei Otis, and Multigenre Writing, taught by Appleman. Along with three other instructors who work with MPWW (and who’ve come to the reading in a show of solidarity, as many of the organization’s dozens of teachers often do), we’ve been escorted through the doors of a lower-slung structure which, on the inside, has all the hallmarks of a public high school; its locker-lined hallways cutting between simple common spaces populated by office chairs, chalkboards, and aging computers. Only the smell of sweat and sewage, not quite cloaked with industrial disinfectant, breaks the seductive spell of normalcy.

Thirty minutes later, the guards begin to bring in small groups of prisoners. Each of the evening’s readers were allowed two guests from the prison population, and nearly all of them appeared cleanly shaven, freshly showered, and dressed in their best institutional garb: freshly laundered gray sweatshirts, pressed dungarees, bright white T-shirts, and carefully kept tennis shoes. “These readings are almost always reverential,” Appleman says. “I wish more people could experience it. It shows how deeply [the participants] respect the act of learning. And it disabuses people of the prisoner stereotype. I mean, they’re better behaved than a convo at Carleton.

“It’s like one guy inside wrote to me once: ‘During times with my classmates, I’m not an incarcerated person. I’m a poet, I’m a thinker, I’m a reader, and I’m a writer. I’m a human being.’”

Otis’s pupils are first up. She’d asked them each to write three biographical sentences to serve as their introductions, but—in the spirit of speculative fiction—every word must be made up. The resulting grandiosity and bravado is as illuminating as it is boisterous. Like the characters in their science fiction, horror stories, and first-person dreamscapes, they are romantic outlaws, mythic “guardians of time, space, life, and death,” and street-wise poets who drop lines no man (or woman) can deny.

Jason Armijo, the first reader from Appleman’s group, shares a collaborative poem about an imagined dialogue with the wider world. Donnie Thames tells the audience that “bullets have no names; they just claim souls.” Eugene RedDay’s delivery is so tender you have to lean in to hear him—and nearly everyone does. Jorge Vargas’s short story ends with a passage written in Spanish, which conjures a murmur of crowd approval. And Caldwell Gray, a hulking man, sheepishly asks that “everyone bear with me,” since it’s his “first time stepping into this lane.”

Through it all, Appleman sits off to the side, beaming and nodding her head gently in affirmation, occasionally mouthing words like “wow.” “I’m not like this in the classroom, but on these nights I withdraw so I can push them into the limelight,” she says. “I always want the work to be more about them in visible and invisible ways.”

Nearly three hours gone, with the ticking clock about to send the evening’s stars back into their windowless cages, the last reader of the night thanks all of the teachers in the room, gives a shallow bow of thanks to Deborah, and, after his reading, asks if there’s time for a song. Appleman gives the thumbs up. He rushes to unpack the carefully kept acoustic guitar he’ll use to perform a piece he has composed for his “seven baby sisters who won’t talk to each other, but will talk to me.” His lithe tenor and Keb Mo–like chord progressions float boundless above the room, barred windows notwithstanding.

“Here’s a guy who, before being locked up for what I sense was a really horrible crime, was in 12 foster homes—in one, they burned the soles of feet—and he actually skipped when he went to get his guitar. He skipped,” says Appleman, who, like her colleagues in MPWW, tries to avoid knowing the details of her students’ crimes to ensure impartial treatment and, for a few fleeting hours a year, to liberate them from being identified solely by their worst sins.

“I could’ve cried. The weight of his horrible childhood was lifted by a gleeful opportunity to share his talent, his words, and his music with—if you’ll excuse the pun—a captive audience. It was like seeing joy in that little dark place. For me, that alone was worth all of the work that led up to our night.”

OVER THE YEARS, I’ve written and edited numerous stories for various publications about America’s penal system, which enlightened politicians, commentators, and researchers agree is an abject failure.

Statista, an apolitical consumer marketing data company, reports that as of January 2023, the United States accounted for 4.2 percent of the world’s population, but houses 20 percent of its prisoners at a conservatively estimated cost of nearly $100 billion a year. That’s the sixth highest incarceration rate per capita in the world. And that means that approximately 500 out of every 100,000 Americans are confined in workhouses, jails, and prisons—both public and private. That’s some 2 million people at any given time.

And those numbers actually reflect a downward trend. In 2018 the United States was number one on the list. The relatively small shift resulted, in part, because moral and philosophical questions aside, it’s become clear to policymakers all along the political continuum that an unbounded carcel state is economically unsustainable.

My reporting has taken me behind the scenes at federal and state courthouses; into victims’ homes, where gut-wrenching stories of irrevocable loss were forever fixed in my memory; and face-to-face with confessed killers who, chained and chastened, have shown no capacity for remorse or change. I’ve also met men and women who’ve come to understand the genesis of their circumstance (economic hardship, racism, child abuse, drug addiction), served their time, and become industrious, inspirational citizens.

Weaned on mass media–generated accounts of life in the Big House (Midnight Express, Scared Straight, Animal Factory, Oz, the list is endless), I’m also petrified by the specter of state-sanctioned confinement. Walking through the front door of a prison, which I’ve done a dozen times, my head spins. The feeling is close to crippling.

So, in mid-January, as I was driving to a photo shoot in St. Paul with Zeke Caligiuri, who was released from Faribault last April after serving 22 years for homicide, I couldn’t help but ask how he emerged intact. How did he avoid the ever-present threat of violence? How did he navigate the spartan conditions with spirit intact? How did he hold onto his humanity in an environment where, as Appleman writes in her book, “dehumanization is one of the required tactics of ‘successful’ incarceration?”

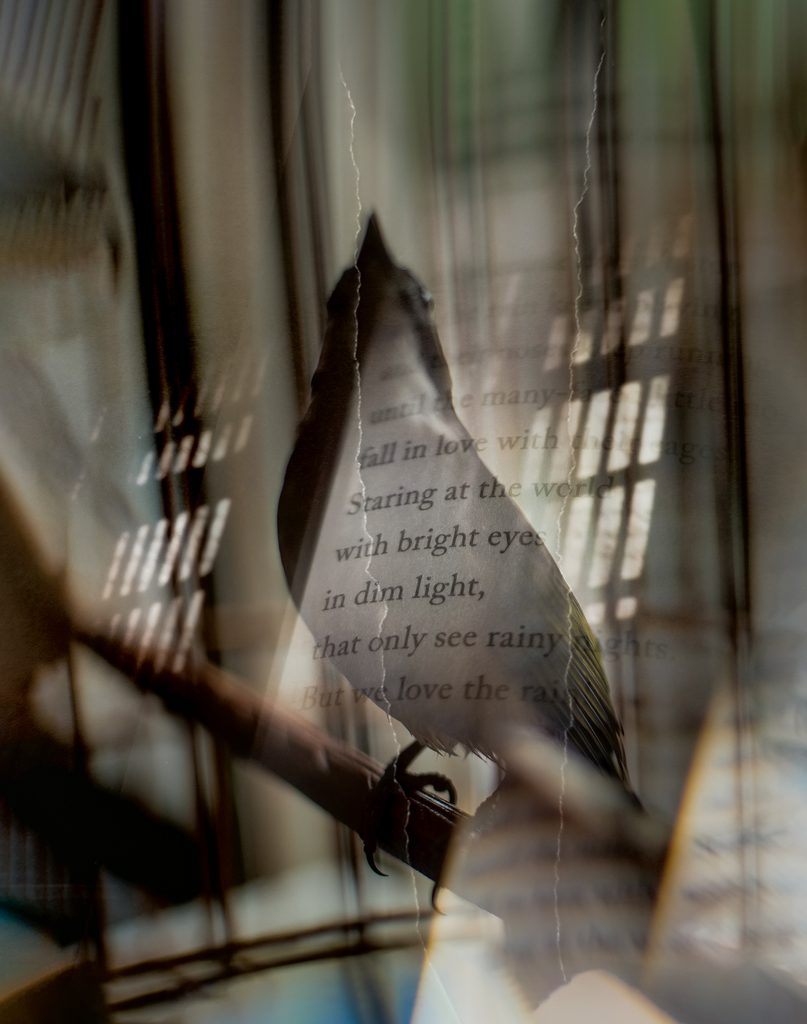

Author of This is Where I am: A Memoir (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), the boyish looking 46-year-old’s answer was as simple as the details of its origin are complex. At the beginning of his prison sentence, for the first time in his life, he managed to fall in with a good crowd—a group of men of all ages and backgrounds who frowned on belligerence and believed in the liberating power of self-discovery.

“When I arrived at [the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Stillwater] there were people that had lived in those buildings for 20 years; men who absorbed me and fed me healthy and productive ideas,” Caligiuri says. “I had a couple of figures who, even though they were confined in the same space, were like grandparents to me. They embraced people with kindness, they took care of them, and they modeled the ways in which community can build even in the darkest places.”

By 2008, when Deborah Appleman taught her first-ever creative writing class for inmates, she’d already been teaching credit-bearing linguistic and literature classes at Stillwater. Quick to say she’s not a writer’s writer (an unnecessarily modest caveat, given the depth and approachability of her 13 books and two textbooks), Appleman became infatuated with the process.

Her students were equally taken. With Appleman’s blessing and editorial input, over a dozen of them went to work on an anthology, From the Inside Out. Letters to Young Men and Other Writings. Poetry and Prose from Prison (Student Press Initiative, 2019). Caligiuri was a contributor, as was Kenneth Starlin, who also provided artwork for the project and is still taking writing classes at Faribault, where he’s since been relocated. (A majority of the nearly 200 incarcerated men Appleman’s tutored over the past 16 years are lifers, most of the rest are serving out multi-decade sentences.)

Like most fledgling writers, the book’s authors loved seeing their names in print. “That first publishing credit? It touches you, because you’re actually doing something,” says Caligiuri. “Instead of letting your most difficult experiences and memories fade, which is tempting, you’re forced to face them and build something lasting.”

Inspired, Caligiuri and another inmate named Christopher Cabrera—who, still inside today, considered himself “more of an organizer than a writer” at the time—cofounded the Stillwater Writers Collective. With the support of the facility’s education director, they hosted informal readings, created visual art, and tried to get as many inmates as possible interested in writing. “It really is one of the most remarkable elements of the story,” says Appleman. “Suddenly, these men had agency over their environment in an environment where they allegedly have no agency. They’re making decisions and recruiting people. They’re editors. They have power and authority in this disempowered state.”

In 2011 Pushcart Prize–winning essayist Jennifer Bowen began teaching classes at the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Lino Lakes, which she found to be a “thrilling and worthwhile experience.” She “serendipitously” met Cabrera through a benevolent educational administrator in the system and, inspired by the Stillwater Writers Collective, founded the MPWW shortly after.

Today, MPWW—funded by the Legacy Amendment, supportive artists, and private donors—sponsors writing programs in all adult prisons in the state of Minnesota, and provides logistical support for 30 teachers (including Appleman) and over 50 offsite mentors, who read manuscripts and provide online feedback. ”Our education in the prisons is not unprecedented,” says Bowen, who serves as MPWW’s artistic director. “But even in places like California, where they have a great prison art program, writing programs are only available in one or two prisons. We can promise that we’re not going anywhere. And that’s a huge thing in terms of building trust. We’ve worked with a lot of the same people over the years, and instructors like Deborah will follow those they’ve worked with from facility to facility to stay in touch and continue providing support.”

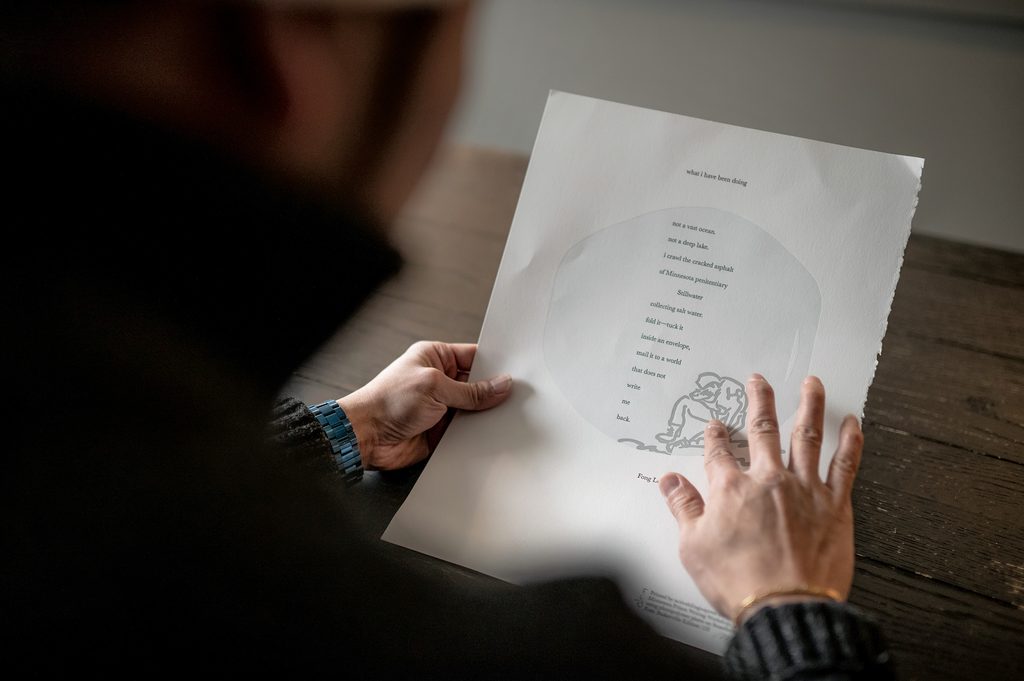

With encouragement from Caligiuri, visual artist and award-winning poet Fong Lee was one of the charter members of the Stillwater Writers Collective, which he credits with “saving his life.” Lee’s life began in a Thai refugee camp and, after his parents immigrated to Detroit, Michigan, went astray. After moving to Minneapolis to find work, Lee was convicted of second-degree murder at age 18 and sentenced to 38 years. He was released in July after serving 17.

“Fong was part of those original classes and immediately understood the vision,” Caligiuri says. “Initially, he maybe didn’t care as much about the writing, but he knew our community was a positive one. And that’s still true. Even if you aren’t a writer or identify as a writer, we want you to be involved.”

Eventually, Lee would embrace the process and, along with Caligiuri, become one of MPWW’s most accomplished pupils; a metamorphosis he says never would’ve happened without Appleman. “English was difficult for me, and the idea of writing in that language was intimidating. But Deborah encouraged me to mesh languages, writing first in [Hmong] and then interpreting it into English. That built my confidence.” Lee says. “The other thing is that she’s never left. She’s been with us the whole time. I mean, she could’ve quit or given up, but she never did. And it’s like, if she doesn’t give up, why should I?”

Still getting used to life on the outside, Lee also credits MPWW for equipping him for the challenges that await in a world suspicious of second chances. “Prison either breaks you or makes you stronger, but it doesn’t channel that strength toward health and wellness. It’s all about keeping inmates agitated and angry. It’s like they want people to leave in a worse condition,” he says. “But if you can cultivate that strength and direct it properly, you can leave this place refined. That doesn’t happen without these programs.”

WHEN APPLEMAN AND I first meet to discuss this story in the Sayles-Hill Campus Center on Carleton’s campus, she steps out of the fall damp wearing a black dress, colorful scarf, and fashionable boots, her hallmark head of brilliant red hair piled high. “I’m pretty hard to spot, aren’t I?” she says with a wry wink and welcoming smile.

It’s Election Day 2022 and, since the professor is not one for aimless small talk or formalities, we immediately begin wondering out loud whether Minnesota Governor Tim Walz will fend off Republican challenger Scott Jensen. Not an inconsequential question given the subject of our meeting.

According to Bowen, programs like MPWW exist at the whim of the Minnesota Department of Corrections (DOC), which can deny access to anyone for any reason. Since 2011, leadership appointed by the governor (including current DOC commissioner Paul Schnell) has been supportive; especially important, she says, because prison reform is “not just about empathy. It’s about policy first.” But nothing’s guaranteed.

The penultimate chapter of Words No Bars Can Hold is about the school-to-prison pipeline and how “rundown physical facilities,” “draconian disciplinary methods,” and segregated learning environments (among other things) can hobble the too-few qualified teachers still standing, and send too many students down the wrong path.

There’s also a trove of anecdotal and statistical evidence, much of it cited in the book’s six-page indices, establishing that—while there’s no silver bullet when it comes to the feloniously imprecise nature of crime and punishment—access to a good education is one of the few proven ways not only to prevent crime, but to rehabilitate offenders.

Even more compellingly, according to the National Commission on Writing in America’s Schools and Colleges, a more inclusive curriculum that transcends the three Rs—and “requires students to stretch their minds, sharpen their analytical capabilities, and make valid and accurate distinctions”—can attract and retain students, especially those with tendencies toward boredom and rebellion.

“There are colleges and universities all over the country that are going to be rendered irrelevant or go bankrupt because more and more people are focused on vocational education,” says Appleman. “What organizations like MPWW are doing is reclaiming the humanizing aspects of reading and writing in the purest possible way. Because, when you think about it, none of these guys have any other motivation. They aren’t getting out. They can’t erase what’s happened to them. It is just the pure art of using language and creating.

“It’s the ultimate test of the liberal arts.”

To read poems and short stories from Zeke Caligiuri, Fong Lee, and others, visit go.carleton.edu/PrisonWriting

Add a comment