For 50 years, the Office of Off-Campus Studies has been expanding Carleton’s boundaries from Northfield to the farthest reaches of the planet.

One of Carleton’s longest-running and most storied study-abroad programs started in 1996, when biology professor Gary Wagenbach crossed campus to ask art professor Fred Hagstrom if he’d like to take a group of students to the South Pacific.

It was supposed to be a one-off excursion, this unusual pairing of biologists and artists over a winter term. But the ocean sunsets, the astonishing landscapes, and the experience of making and studying art—as well as history, politics, and culture—while immersed in nature was too good not to repeat. And so began Studio Art: South Pacific.

Every other year since, for more than two decades, Hagstrom has taken students to Australia, New Zealand, and the Cook Islands to make art, study history, observe the effects of colonialism, discuss cultural differences, learn from biologists in the field, visit museums, and attend lectures. Along the way, Hagstrom refined the 10-week program with the help of the Office of Off-Campus Studies(OCS), a five-person department that serves as travel agency, counseling center, research group, and embassy for students. OCS also helps faculty members with the practical considerations of off-campus travel, from planning logistics and financial aid to ensuring that programs fit into Carleton’s accreditation standards.

“At Carleton, study abroad is not the cherry on the top. It’s integral to academic learning and personal growth,” says Helena Kaufman, director of OCS. “It’s essential to developing global citizens—people with initiative and civic engagement.” For nearly 20 years, Kaufman has helped students discover and access off-campus study opportunities that fit their goals. Some have a specific destination in mind. Others seek guidance from Kaufman and her team, who watch over a massive catalog of opportunities, including faculty-led programs and programs offered through other institutions.

It’s something of a Carleton tradition. Andrea Grove Iseminger ’59 was the first full-time director of OCS and instrumental in the program’s growth. While just 10 percent of undergraduate students in the United States study abroad each year, more than 68 percent of Carleton’s Class of 2019 participated in 100 different programs in 53 countries. These numbers are due in no small part to OCS, which is celebrating 50 years of sending Carls out into the world. Hagstrom says that the multidimensional lessons of dislocation and discovery underscore the lessons taught on campus.

“Campus is a very busy environment and so it’s not as contemplative as it could be. When you get students away and they are doing art all the time, it’s a very different rhythm. You get a different level of work,” says Hagstrom, who also encourages students to consider the broader effect of their travels, not just on themselves but also on their host countries. For instance, he talks with participants about the difference between being a tourist and being a thoughtful visitor. They discuss environmental impact, and he encourages them to recognize their own cultural traditions as they learn about other cultures. “If you go about it right, learning happens all the time during off-campus study,” says Hagstrom, who is retiring in 2021. “Even when you walk into a store or read a newspaper, you are learning. The differences are themselves a lesson, if your antennas are out. Travel is about learning all the time.”

Hagstrom took his final group abroad last winter. Students—who watched him say good-bye to the biologists, Maori artists, and others who have assisted the program over the years—learned another invaluable lesson: friendships formed with people who live on the other side of the planet are meaningful. “These are some of my best friends in the world,” he says. “I’ve watched their kids grow up. I’ve watched members of the community die. Every time in the past, when I said good-bye, I said, ‘See you in two years.’ So this trip was bittersweet.” Off-campus study isn’t a prerequisite for a Carleton degree or for a successful career. That said, breaking out of the classroom turns academic learning into tangible understanding. It is highly encouraged and supported by the faculty, financial aid, and OCS. “If a student wants to study abroad, we find a way to make it happen,” says Kaufman. “We begin by asking students about their interests, majors, languages they speak, thoughts on their Carleton experience. Then we ask why they would like to study abroad and what their main goals are. Usually, things get very interesting very quickly, and we can recommend specific programs.”

ACCIDENTAL DIPLOMAT

CHARLIE BENTLEY ’13

Charlie Bentley didn’t arrive on campus with a passport full of stamps (“Travel wasn’t really part of my family’s budget or lifestyle,” he says) and remembers being a little intimidated by his more worldly classmates. “So many students had graduated from prestigious high schools or had the socioeconomic support to do incredible things,” the postal worker’s son remembers. “I was kind of nervous to speak up in class. I didn’t realize my opinion mattered.” The chance to study abroad changed all that. Bentley chose a seminar in Japan with Professor Mike Flynn’s linguistics program. Carls would be partnered with students in Kyoto and explore the city and culture with some guidance, which appealed to the first-time traveler. “We were thrown into an environment where we were all on the same playing field,” he says. After a crash course in Japanese, the students visited universities, cultural sites, and urban neighborhoods. “I found every part of it completely thrilling,” Bentley recalls. “It made me realize that I was really good at connecting with people. I gained an enormous amount of self-esteem.”

One afternoon, Bentley found that he was lost in the city during a sudden downpour. To escape the storm, he ducked into an onsen, a public hot spring bathhouse. “It was nothing I ever would have done, but Professor Flynn had mentioned that we should go to one if we had the chance. It was an amazing experience. I found myself in this beautiful place, relaxing and looking up into the trees. After that, everything seemed easier.” Back on campus, the linguistics and cognitive science double major merged his interests by organizing an American Sign Language club. He graduated magna cum laude and delivered one of the commencement addresses for the Class of ’13. He then became a Thomas J. Watson Foundation fellow and studied disability issues in Africa. Back in the States, he created a trauma counseling program at Massachusetts General Hospital, worked on disability discrimination lawsuits, and studied at Tufts’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. In 2019 he became a foreign service officer with the US Agency for International Development. He will spend the next three years in the Democratic Republic of Congo. “When you look at the path I’ve taken, it seems like a very straight line,” he says. “But it all begins with that first study abroad experience. Had I not done that, none of those other things would have happened.”

EXPEDITIONARY ARTIST

MARIA CORYELL-MARTIN ’04

On the walls of the OCS office hang a set of watercolors painted by Maria Coryell-Martin, a traveling artist and arts educator. She arrived at Carleton with a plan to study field science but during her first winter on campus found hers elf wanting to bring color into a world t hat had gone dormant under the weight of snow and studies. So she took a studio art class. The experience proved infectious. “I realized that I wanted to study art,” she says. “And when I learned about the South Pacific program, it looked like a way I could bring my interest in nature and biology together with my art.” She joined art professor Fred Hagstrom’s program her sophomore year. As she captured plants, land formations, wild life, and village scenes in her sketchbook, she discovered that creativity and scientific study could be fused into a way of life. “I realized t hat this was what I wanted to do and so I got down to it,” Coryell-Martin recalls. “I sat down and began to make art every day.”

After the trip, Cor yell-Martin immediately began to plan another. She kept her passport and sketchbook close together as she s et off for OCS programs that took her to Mali to paint West Africa ecosystems and to Alaska to create an artistic record of the Juneau Icefield Research Project as an artist-in-residence. “I formed an identity of myself as an ‘expeditionary artist,’ ” she says. After graduation, she was awarded a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship to travel for a year, exploring remote regions through art. In the years since, she has joined field scientists around the world to observe forests, seascapes, and wildlife, and the urban skylines and oil fields that are replacing them. Having painted melting ice in Alaska, Greenland, Antarctica, and Canada, she’s now visited every continent in a series of expeditions and residencies.

PATHFINDER

HANNAH KOENKER ’00

When she arrived at Carleton in 1996, Hannah Koenker figured she’d be an English major and end up an academic like her parents back home in Urbana, Illinois. During her junior year, though, that path was no longer appealing. “I remember feeling a little lost at that point. I wondered: Should I try law school, publishing, write for radio, become a journalist?” she says. Then her French professor, Chérif Keïta, mentioned that it wasn’t too late to join a winter-term trip to Mali. “I remember being up for half the night, thinking about how this was going to change my life,” she says. “You know, all of the things that I was going to learn and all of the experiences that I was going to have. I could not sleep for the excitement of it.” In Mali the students experienced upper-class urban life with host families in cosmopolitan Bamako and in rural villages with no running water and electricity that came from small solar panels. “They welcomed us with a big dance party, which, to me as a midwesterner, felt like a bit much,” she says. “But that’s just how things are done there.”

Koenker had lived in Paris during a gap year and her language skills helped her forge meaningful connections in French-speaking Mali, where she realized it was her French minor, not her English major, that would guide her forward. After graduation, she worked on AIDS prevention in Gabon as a Peace Corps volunteer, returned to Mali to work as a family planning consultant, and became a malaria program officer through Johns Hopkins University, where she received a master’s degree in public health. “The smallest thing that I’ve taken with me, which is one of the largest in the end, came from my host father in Mali. He said, ‘Il faut être utile’—‘You need to be useful.’ That’s the point, right? What are you doing if you’re not helping someone or doing something useful?” she says. “It’s also an unstated principle at Carleton. They aren’t educating students to do frivolous activities. They want us to go out and make the world a better place.”

TRICKLE-DOWN TRAVEL

DAVID WELNA ’80

David Welna is celebrated as an international reporter and National Public Radio correspondent. At Carleton, though, he was known simply as the little brother of Chris Welna ’78. In fact, it was Chris’s study-abroad experience that helped ignite David’s interest in exploring places beyond southern Minnesota. “I grew up in a family with nine children, so resources were stretched and I did not get on a jet plane until I was 17 years old,” says Welna, who grew up an hour south of Northfield. “Our parents wanted us to be aware of the wider world, though, so we always had newspapers and books around, and we listened to public radio. I was friends with foreign exchange students in high school, but I did not conceive that I could become one until my older brother Chris studied in Brazil while he was attending Carleton. He came back with a Brazilian guitar and stories about living with a host family with 14 children, and it sparked something for me.”

After high school, Welna took a gap year to live in Mexico before starting at Carleton, where he continued to explore Latin America through an Associated Colleges of the Midwest program in Costa Rica. “We visited farming communities, spent time in the city, and if we wanted to talk to the secretary of education, we could just make an appointment,” he says. “It was like being in a 24-7 seminar on every aspect of life.” (Decades later, while Welna was interviewing Colorado Senator Ken Salazar for a story, he realized that the two had already met: Salazar attended the same Costa Rica program through Colorado College.) After graduation, he traveled to Argentina as a Thomas J. Watson fellow and did a little freelance reporting that put him in the right place at the right time; when the Falklands War broke out in 1982, Welna covered the conflict for the radio network Mutual Broadcasting System—until the competition stole him away. “NPR heard me reporting from the Falklands, and I have reported for them ever since,” he says. “It wasn’t so much that I’d decided to become a foreign correspondent. The things I was interested in and the experiences that I had just kind of lined up.”

PHYSICS AMBASSADOR

ERIK LAGERQUIST ’19

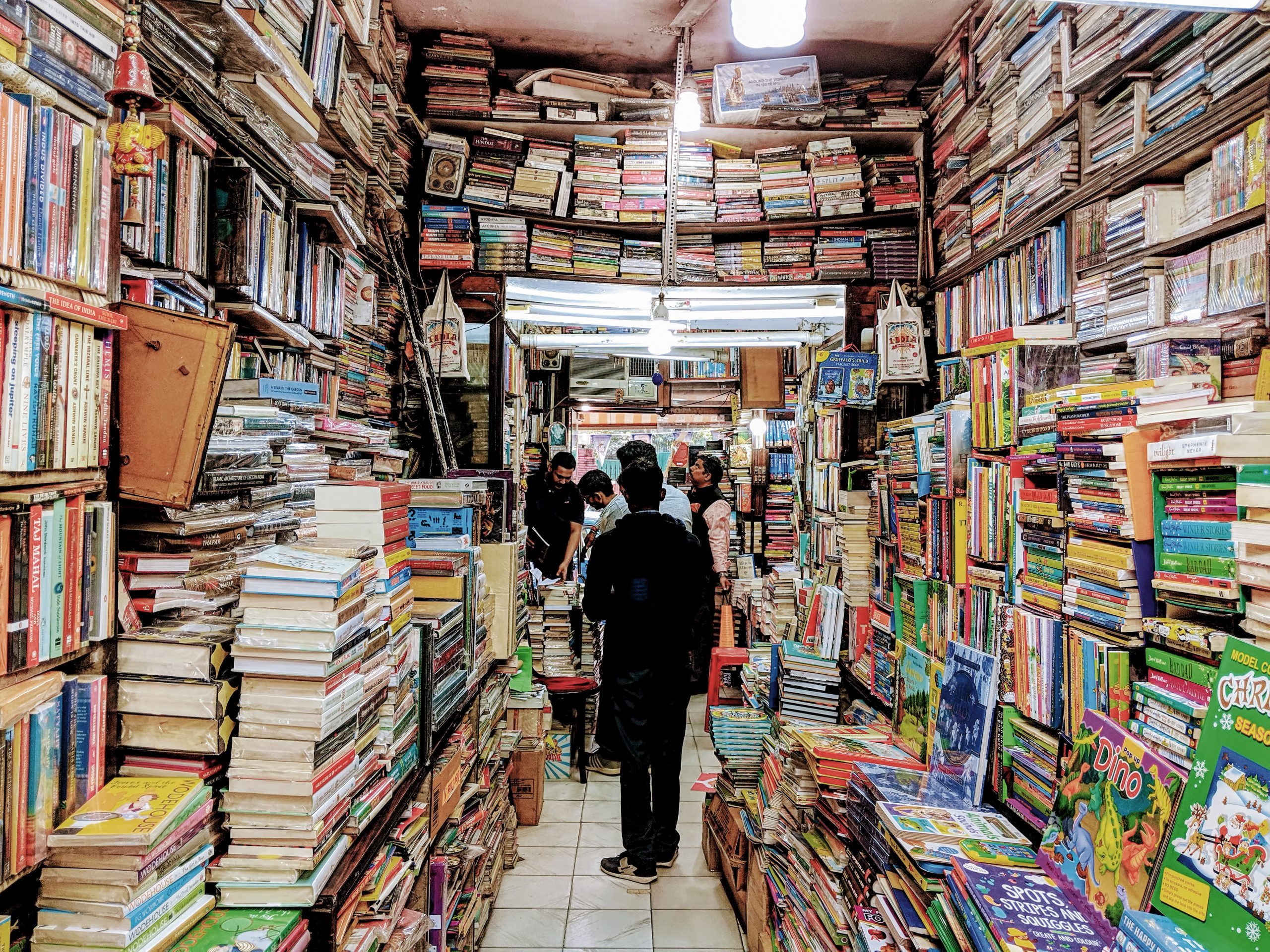

The study of physics is no cakewalk. Erik Lagerquist knew he had signed up for an especially rigorous program. He chose Carleton so he could balance that intensity with other experiences. “I really wanted to travel abroad and study languages, and I knew Carleton would let me do that within the sciences,” he says. During his sophomore year, Lagerquist joined a two-week program led by physics professor Arjendu Pattanayak that focused on sustainable energy systems in Delhi. Even a short trip requires significant planning. “I remember all of us sitting in a room at OCS learning how to apply for visas and making sure we could get into the country,” he recalls. “We also had meetings about health and safety, travel procedures, and other basics.” Carls took courses with Indian physics students and worked with a local nonprofit to install sustainable energy systems. It was applied physics done on a tight timetable. “India is so huge and diverse that two weeks is not enough time to absorb everything that’s going on there related to sustainability and energy, not even close,” Lagerquist says. “One night, the Indian students and the Carleton students just sat around and chatted, and we found so many parallels between our situations. I wanted to visit a new place and get to know the people there.”

When he returned to campus, OCS director Kaufman suggested a Spanish immersion program based in Quito, Ecuador, that focused on community development. It had a strong arts component, but no science. “I was excited about that part. Physics is pretty intense and I wanted to do something new and different for a while,” Lagerquist says. “When I got back to campus from that trip, I felt refreshed and ready to do math and science again.” As he had hoped, Lagerquist made meaningful connections with Ecuadoreans, many of whom had never met an American. “I realized, ‘Wow, I’ll largely represent what they think of American people,’ ” he says. “It’s important to understand that when you leave campus, you are representing Carleton—and you are also representing the United States.”

TRANSATLANTIC DOWNLOAD

DAVID LIBEN-NOWELL, COMPUTER SCIENCE PROFESSOR

In an era of global information and economic exchange, study abroad prepares students to work with multinational teams in business, scientific collaboration, and government. Computer science professor David Liben-Nowell began working with OCS nearly a decade ago to develop a study-abroad program that would help computer science students view their work in a historical, global, and social context. In the summer of 2019 he led 20 students to England to study the history of computing. The group toured Cambridge, the Science Museum in London, key World War II sites, and Paradise Mills, where Jacquard looms have run since the start of the Industrial Revolution. Students saw how textile patterns were stored in punched cards—a precursor to computer programming. The course centered on two major moments: the development of the Analytical Engine in the mid-1800s by Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace, who took inspiration from textile loom programs; and the code-breaking era of World War II, led by mathematician Alan Turing, who invented an electromechanical computational machine that decoded encrypted Nazi intelligence. Although his contributions helped the Allies win the war, as a gay man in repressive postwar England, Turing was grievously persecuted. Likewise, Lovelace’s contributions, coming from a woman in the 1800s, are only now appreciated.

“Good computer science education should teach us to think about the broader context for all of the things that we do,” Liben-Nowell says. “Usually it’s more about what the implications of technology are and how it’s changing the world for better or for worse. But in this case, it’s also thinking about the people who are involved and what brought them to the moment that mattered.” While almost any topic can be addressed in the classroom, Liben-Nowell says, seeing the places where history happened brings lesson plans to vivid, complex life. “Being at World War II sites with a group of 20-year-olds was powerful because it made us think about how, in a different era, under different circumstances, they might have been on the beaches at Normandy,” he says. “That’s a very interdisciplinary view of computer science. That’s not universal. But many other disciplines are part of this field, so that’s how we teach it at Carleton.”