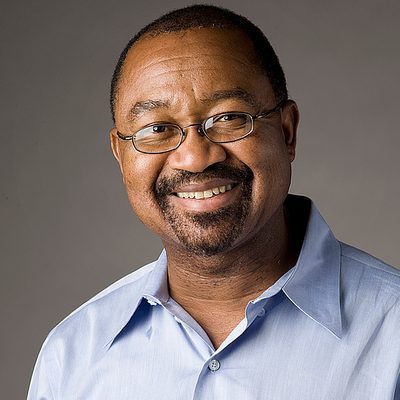

A Discussion with Faculty Director Chérif Keïta

What inspired you to plan Society, History, and Popular Culture in Senegal? What did you hope to accomplish?

What first inspired me to plan this program is that the Mali Program ended, which used to be a term-long program. So when that program stopped, I realized that West Africa was still very important for the French program and the French department because we call ourselves “French and Francophone” studies. So really, for the integrity of the program and so we don’t just feature France, but feature the variety and diversity of the French speaking world, Africa is a big piece that you cannot just cut. I felt that we needed to figure out how to have one foothold in West Africa. The peaceful place – knock on wood because Mali was stopped because of security issues – luckily right next door, is Senegal, which in many ways resembles Mali in terms of African cultural foundations and development. I thought Senegal would be a good place to go as an introduction to Africa.

Senegal not only has the advantage of being similar to Mali in terms of culture, but it also shows the whole spectrum of the colonial experience. From the time of the slave trade all the way to today. This is something you did not have in Mali since Mali was colonized later and Senegal was the first French colony. In Senegal you have the transatlantic connection through the slave trade but you also have the actual colonial experience with France occupying Senegal which lasted from the early 18th century all the way to the mid 20th century, and then you have independence. So the whole spectrum of the French colonial experience, you have it there. Senegal is a vibrant country where you can see democracy at work, because it is maybe the only country in West Africa among the former French colonies where there has not been a military coup, where the notion of French Republic has been experimented and seems to work. So we look at how did it work, is it because of the length of the colonial experience as opposed to other places? How do the political institutions work? There is something for everyone.

So I felt that Senegal was the perfect example and opportunity. Although I had to use that experience differently because of time constraints, the fact that it comes in addition to a fall term course already taught on campus gives a chance to already prepare and to introduce students to that colonial experience through literature, film, popular culture, and music. This gives people a visual picture to already interpret what they see in terms of the different stages of the colonial experience.

What makes this program different from other study abroad programs?

There is something for everyone on this program. For the history buff there is the slave trade, which really should be of interest to anyone living in America as the slave trade is a part of the fabric of America. To go to the source of where the slaves came from, it can be a very moving experience. But it also appeals to someone who is interested in political science, international relations, or interested in Africa and how nation building happens in Africa. It also appeals to people who are interested in literature, because the first president of the country was a world renowned poet who always saw himself as a writer and man of literature on the political stage, which you don’t find in a lot of other countries. This is a man who really emphasized culture.

Senegal also helps show what it means to be a francophone country – not to be a French country but to be a francophone country. Does that mean that everyone speaks French? No, but it means that French is the official language. It is the imposed language, so it comes with the position of power, and in the context of independence, how is the language negotiated? So going there you get a sense of how African languages are competing with French through the media, radio stations, and the internet. How are those languages coexisting? It is only when you go there that you understand that French is there but its position has a limited sphere compared to African languages.

This program also has a personal dimension for me. My late father, as a young man coming from the French Sudan which is now called Mali, was a farm laborer and used to go to Senegal to work as seasonal worker. So Senegal was a part of his experience and then that’s where my father enlisted during the Second World War as a colonial soldier to go fight in Europe. So we also go to military museums connected to Africa participating in the Second World War. In fact I bring my father’s military papers with me. It’s like I’m following in my fathers footsteps. But I’m also following in my own footsteps because as a teenager, my family in Mali used to send me to spend my summer vacations in Senegal with family. So it makes the trip more meaningful for the students.

What does a typical day look like on your program?

A typical day starts with breakfast at the hotel where we stayed the night before. The hotel is our base and then we go to a place where we have classes and lectures. We have different specialists that come and talk to the class, like how Dakar was urbanized and settled for instance. After we have a lecture like that, we go visit Dakar, take transportation and go around to visit different neighborhoods. We may stop for lunch somewhere at a restaurant (Senegalese food is delicious). Then we might watch a film that goes along with those themes at a center or go back to the hotel. After that we would let the students go around on their own. We also have some days that are spent on the road on the way from one city to another. In that case we usually stop along the way to the next city. It is a very mobile program, so we need to be on our feet, or wheels, most of the time.

What does the housing situation look like, and what are the benefits of this living arrangement to students?

Because of the short nature of the program we do not have any homestays in this program and the students stay in very nice hotels. Since this is our second time going we already know them well and we have very nice and courteous staff that accommodates us well and with good food. One example of a hotel we stay at is the Maison Rose in St Louis, where the hotel itself really helps students understand the historical and cultural context of the town. The decorations contain art from the 18th century and tell the stories of the biracial women that used to live in this colonial town. It shows students that colonialism was also a mixing of people, and that those people who are at the point of convergence of those two cultures drew a political strength out of that. So staying in a house like that really makes things real and overall enhances the students’ experience.

What are you most looking forward to?

I am really looking forward to developing new ideas further because every time you go, you see a new opportunity to make the program richer. Each component you can see you can make more use of it or stretch it. I also want to go back and relive these moments. For instance we take a boat to go to the island of Gorée that is a UNESCO wold heritage site where slaves were shipped. Just thinking of the significance of the transatlantic slave trade and going there is a memorable experience. So I always look forward to going back.

What advice would you give to students to encourage them to study abroad during their Carleton career? What benefits do you see to the experience in general?

My philosophy in life is that you don’t know someone until you go to where they come from. The reason why I take students overseas, to Africa, is that when we come back they tell me now that we have gone to Africa with you, we now know more about you, because we now understand why you are the way you are. So people may see Africans out of the African context, but how do you really know Africans? Go to the African continent. I think you’ll understand a lot of the cultural values that African humanism is based on. So I see it as an amazing opportunity to really begin to understand Africa.

Chérif Keïta is the William H. Laird Professor of French and the Liberal Arts. He has been at Carleton since 1985.