Living London Through a Lens: A Discussion with Faculty Director Peter Balaam

Nine questions. Five photos. One Instagram account.

In an innovative Insta-interview, faculty director Peter Balaam answers a series of questions pertaining to the Living London: City, Scene, Anthropocene program. See more photos on the Living London Instagram account.

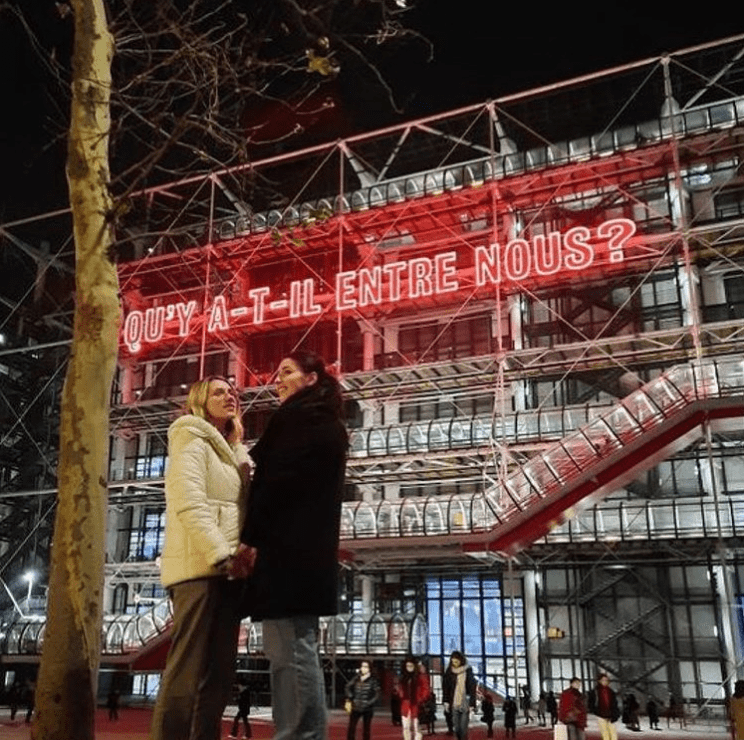

In your Instagram caption for this photo, you claim that the words written in this neon installation (“Qu’y a-t-il entre nous?” or “What is there between us?”) could be the unofficial motto of the Living London program. What was it about these words that captivated you? How does this question encapsulate the essence of the program, and more broadly, of the study abroad experience?

So glad you chose this post! For obvious reasons, we tend to think of cities as places, right? As destinations to arrive at or visit, to map or traverse. But on this program I want to take steps to practice experiencing London (and more briefly, Paris) not as place so much as process, as a force of human interests coming together and unfolding in time, and in any moment dancing before our eyes. I’m after the City as living and changing entity, whose particular spirit we can sense, smell, touch, converse with, and get to know. My program is really about the metropolis as a stage for human being, human experience, and all the relating and discovery that implies.

At Carleton, I teach an A&I Seminar called “Walt Whitman’s New York City,” which is built up from that incomparable poet’s sense of being met in the Person of New York City by another, a mate, or fellow-traveler: “O City!” he calls, “Incarnate me as I have incarnated you!”

This picture of an installation by neon artist Tim Etchells on the Pompidou Center facade in Paris asks a question that invites us beyond tourism and toward thinking of the City as a counterpart or conversation partner, antagonist, or lover: O bus-ride, O Tubestop! O London, my dear — just what is there between us today?

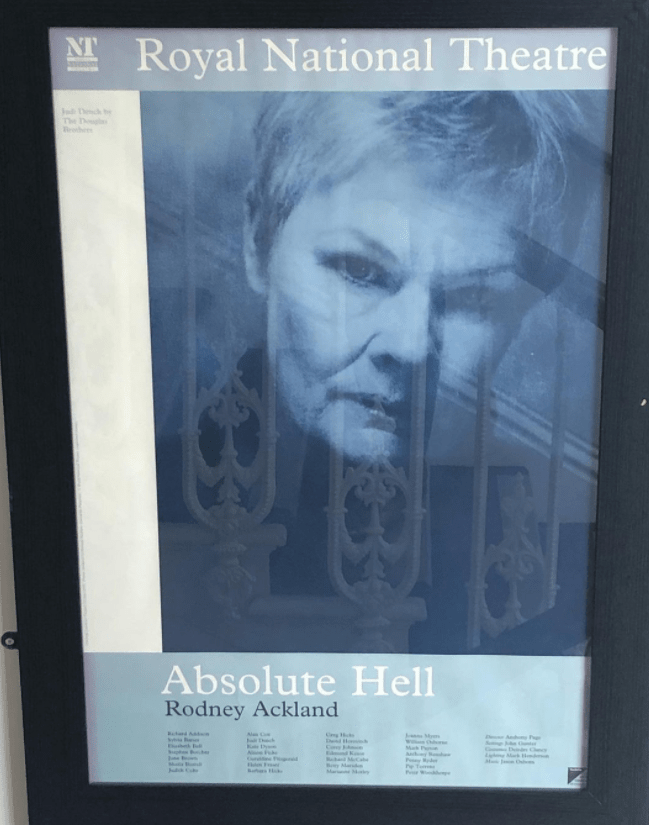

Why is theater such a large component of the Living London program?

This program was built around London theater when it was begun 50 years ago and theater has always been the program’s anchor. For range, quality, variety, sheer panache; for the contributions of local, national and international traveling companies that it draws annually; for the culture of theater-going it creates around itself– the theater in London is really special. This program offers the deepest dive into contemporary English-language theatrical art available anywhere on the planet. We’re not talking about Wicked and The Lion King; this is an experience that is really possible only in London.

What is it about theater performances that makes them such a strong teaching/learning tool? What important lessons do you hope your students will learn by attending these performances?

In English we teach and study verbal artifacts of various sorts, right? — things made out of words– novels, stories, poetry, plays, criticism. And in doing literary study we exercise critical faculties such as interpretation and sense-making, and we fashion analytic and aesthetic judgments to respond fully as we can to what literary works do. The theater is a powerful medium for housing and structuring such verbal ingenuity and our reception of it. And it infuses the whole project with delight. Theater is made of a few great sources of pleasure and of perennial interest: the sheer bliss of using our senses and relational impulses in a focused way; encounters with human story-telling and its ubiquitous work of transformation; the human body in all its mundane glory, beauty, and frailty; and the sounds of human voices in the air, speaking, praying, shouting, singing, seducing, mocking, condemning, desiring, inventing. It’s not a lesson; good theater is a jolt and a ritual and an invitation to remember and to feel.

In the past, how have students reacted to the theater component of the program? Have they enjoyed it? Struggled with it? Both?

They have raved about it. The theater aspect surprises some people, I think, especially those who aren’t really sure if they really like theater all that much. We see two to three plays each week and discuss and debate our responses to them and do a bit of writing about them. Once we get into the rhythm of theater-going during Week One students quickly come to feel very lucky indeed to have this opportunity to study an art form so deeply and richly and intensely. It’s a phenomenal treat, and it changes you; and students quickly get that.

What are these photos, where were they taken, and in what ways do they represent (or misrepresent) the reality of urban environments (such as London and Paris) today?

These are 8 separate images I took with my phone on a walk through the 10th arrondissement in Paris in early December. They are themselves photographs by a person called Jean-Baptiste Pellerin, portraits of regular people in Paris, mounted inside weather-tight plexiglass frames maybe 4” x 7” in size and (illegally) glued to walls along the street. In certain districts you can see this artist’s work, always without comment, literally everywhere and I confess I find it joyous. (I probably snapped shots of 30 more not shown here) A form of vandalism? An invitation to reflection? An encyclopedia of human instances? I don’t know! What do you see in them?

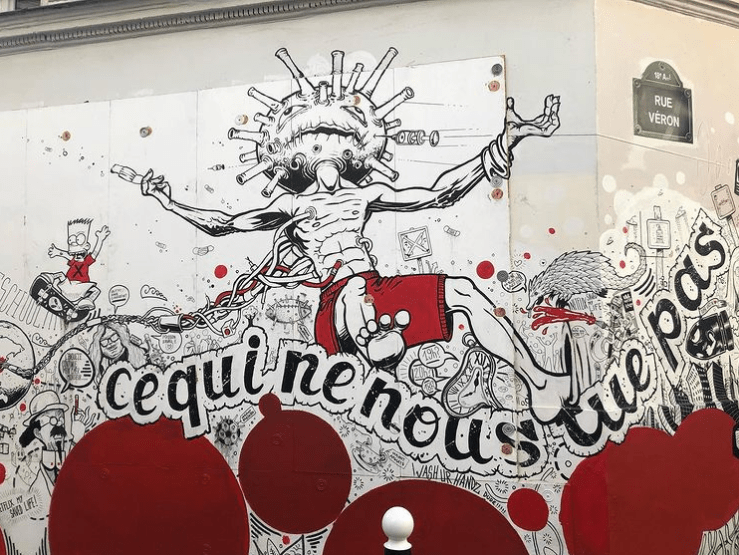

How does street art contribute to the culture and atmosphere of urban settings? In what ways is it different from other art forms?

Street art is illegal and, as such, anti-elitist in its radical accessibility to anyone happening by on the street. No galleries, no schools, no academies exhibit, curate, explain, vouch for, buy, sell, or otherwise house such work. Meanwhile, some of it is, despite its exposure to the elements and the street, very technically accomplished… not so much this image, which is good but basic illustrator’s stuff. Still, we note the playful mischief here of an elaborated political graffito, an account of the frustration and confusion of regular citizens bearing up under weeks and months of pandemic shutdown.

The answer to your question is, I think, street art contributes a lot to the atmosphere of the City– probably a lot more than do far more celebrated works like Van Gogh’s Irises or the Venus de Milo a few miles away in the Louvre museum.

A new way in which such commando artists are beginning to be like “other art forms” is that thieves very skilled with their crowbars now come around and surgically remove whole square meters of plaster wall in order to make off with such work, remount it, and put it up for sale on the black market. The work shown here is immense– it would be very hard to steal– you’d have to make off with a whole house– but the works of certain street artists in Paris now command huge sums on the black market.

Does street art serve a purpose? If so, what might this purpose (or purposes) be, and is street art effective?

Well, you tell me! You selected the images to highlight for our interview; I wonder why your eye fell on this one…? In what ways does such work provoke or disrupt or allure or offend or skewer or reassure… or just connect? And connect what to what? What’s happening within you as you respond to this enthroning of a ripped masculine King Covid, “reigning” over a scene of social chaos? Where do we place the parameters of art’s “purpose” or “effect” in the 21st century? How, if it does, might such artwork speak to those purposes? These are open questions in our era and street artists are asking them, and they are asking us to ask them. I’m all in, completely enticed by this illegal and ephemeral and technically accomplished work. I find it a telling and intriguing element of 21st century life in the metropolis.

In your Instagram caption for this photo, you cited that this was taken in Bloomsbury. Was this photo taken from one of the buildings that students will be housed in? What does the housing situation look like for the Living London program?

This was the window into the garden at the hotel where we stayed in November when seeking out new classroom and living spaces for the program. For many years, students have been staying in Bloomsbury. An exciting feature for winter ‘23 is that for spiffy housing and classroom spaces we will be moving to a new provider located a few miles to the west in South Kensington.

What might a typical day on the Living London program look like (if such a thing even exists)?

A typical day might entail breakfast on your own at the students’ flat, the one, I hope, that stands just across the street from Kensington Gardens. Then, jump on the Tube to the meet-point for our “Urban Field Studies” course, in which our instructors– an archaeologist and an observational drawing-teacher– will lead us through the week’s featured encounter with one of London’s many off-the-beaten-path districts. Done with class at noon or 1:00, students could find a place to grab a bite locally and further explore the streets we’ve been learning about that morning. Free time in the afternoon could entail meeting up with an open-air exercise group you might join in Hyde Park or a work-out in the gym at Imperial College near our flat; or, it could give people time to grocery shop and cook up a meal together. In the evening, using public transportation, we might head east and across the river to the National Theater for one of the week’s shows. Coming out after the show, in that inky black night, the blazing lights of the Town all around us and reflected in the flowing river, we might walk north and west as a group, crossing the Thames on Waterloo Bridge and into Covent Garden. We might step into a pub, or grab a bite in a curry shop. We might jump on the Tube or a bus heading west again for the flat in South Kensington.

Peter Balaam is an Associate Professor of English. He has been at Carleton since 2003.