The right bird’s song: Biology professor and musician uncover the inspiration behind Antonín Dvořák’s “American” String Quartet

Towsley Professor of Biology Mark McKone and his husband David Beccue discuss their recent research and scholarly paper that digs into both music history and ecology—all within a familiar musical movement that was inspired by a bird.

Mark McKone, Carleton’s Towsley Professor of Biology, reached a professional milestone in October 2020: his first article published in a music journal. The paper, titled “The Iowa Bird That Inspired Antonín Dvořák’s American String Quartet in 1893: Controversy over the Species’ Identity and Why It Matters,” digs deep into both music history and ecology. It argues that the birdsong inspiration for the third movement of Dvořák’s “American” String Quartet in F major was not the scarlet tanager as has long been believed, but the red-eyed vireo.

McKone didn’t make this breakthrough alone. The second author on the paper is David Beccue, nurse practitioner in the Minneapolis Veteran’s Affairs Comprehensive Pain Center by day and musician in VocalEssence Ensemble Singers by night. When I reached out to learn how this unlikely pairing was born, McKone said, “My co-author happens to be my husband, so it would be easy to interview us together.” So, I did.

Greta Hardy-Mittell: How did you two come up with the idea for this paper, which is a step in a different direction for both of you?

Mark McKone: Yeah, that’s for sure! I guess I should take the blame.

David Beccue: It was Mark’s idea.

MM: We met late in life, in 2012.

DB: Well, let’s say mid-life. I wasn’t as in tune with nature until we met. I was more of a musician before then.

MM: I actually was pretty interested in music. When I was going to undergrad, I couldn’t decide: Am I going to be a music major, or a science major? I took piano lessons forever. But the truth be told, I think I was not very talented. My real love and talent is science. Then when I met David, I was reinspired to love music more and understand it more.

I remember the time that it started: we were staying in an Airbnb in this very nice wooded area where there were a lot of birds. He was becoming more and more aware of birds, and I was becoming more and more aware of music.

Minnesota Public Radio was on, and as so often happens, the announcer said, “Now we’re going to listen to Dvořák’s American String Quartet, and make sure you listen for the scarlet tanager in the third movement.”I thought, “Oh, OK, I know scarlet tanagers pretty well.” We listened to the whole movement, and I thought, “Well, there’s no scarlet tanager in this movement.”

I looked it up on Wikipedia, and sure enough, it mentioned the scarlet tanager. I thought about it a little more, and looked at what was published on it, and more and more I was convinced that it was wrong.

DB: I stayed out of the whole topic at first, but Mark said, “I want you to be involved in this in some way.” I thought, well, I can analyze music and describe it, but that’s not going to help your point at all. But when I did start to analyze the piece, all these really cool patterns came out.

We’d discovered this one little part where everyone says, “Those four bars, listen, that’s where the vireo sings!” We realized that’s a secondary thing. If you look in the opening measures, the birdsong is right there. It was never analyzed that way in the past. That was when I got fully vested in it.

GH: Could you give a summary of the paper for someone who hasn’t read it?

MM: The famous story goes that Dvořák found himself in Spillville, Iowa, for the summer and wrote this piece in just a matter of days. And it’s in the lore that it was inspired by a bird. There’s way more scholarship than I could ever have guessed. I tracked it all down, and sure enough, it’s Dvořák himself who talked about a bird that inspired the song.

So that’s true: the movement was inspired by a bird. But then the question became, what bird? And it wasn’t until the 1950s that a Dvořák scholar in Britain, who had never heard a scarlet tanager, indirectly, using a visual description, decided it was a scarlet tanager. And that became the truth. It was repeated over and over again until 2016 when a fellow named Floyd, a bird person in Iowa, put a note in Iowa Bird Life saying it was a red-eyed vireo.

So, we took that and analyzed the piece again. The second part of the lore, as David said, is that it’s just these couple of measures. But when you analyze it, especially when you know it’s a vireo song, the whole movement is built around this bird song. This is what we’re arguing.

GH: Who are you hoping will read this piece?

DB: When I took music history seminars as a grad student, we were always passed along the same stories. Musicians do a lot of scholarship and analysis, but I don’t know that those stories get challenged very often. I heard this story, and it was never challenged. I’d like to see music history professors read it and tell their students, well, here’s what these guys up in Minnesota say… and they’re not even musicologists!

GH: Speaking of, Mark, your other papers are all very ecological. What was it like writing a music paper instead?

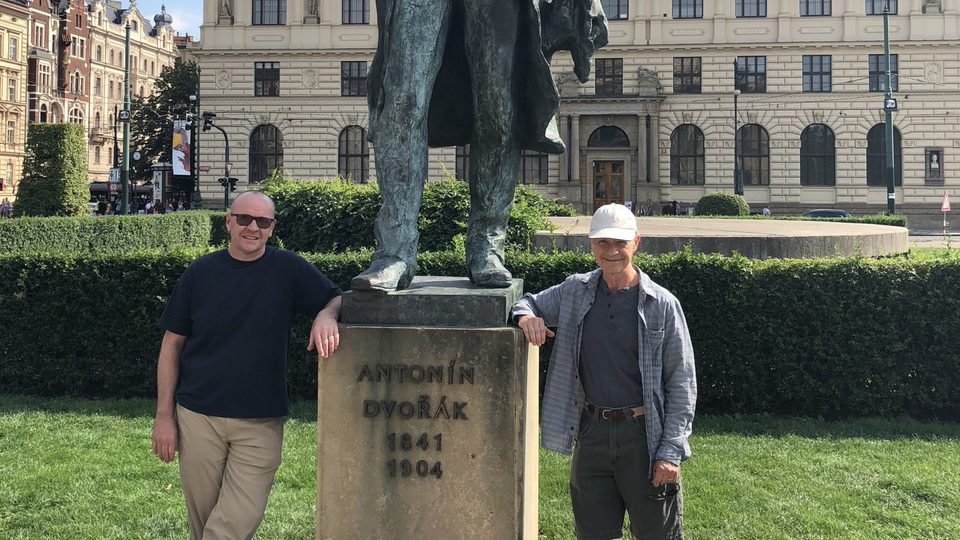

MM: It was really a learning curve. The kind of scholarship was so different: I was digging around in papers and letters. One part that was really fun was going to Prague! We went to the Dvořák museum and looked at the original correspondence between Dvořák’s secretary Kovarí̌k and this biographer that led to the whole legend getting started.

DB: We also had a driver take us out to the estate where Dvořák spent his summers. It was just fun to be where he was. If you looked out over the rolling hills, you could be sitting outside in Spillville, Iowa, and it almost looked the same.

MM: It was amazing, how similar it was to going to Spillville, to the very place where he heard the bird. There’s a reason, I guess, that Czechs ended up going where they went.

One of the big things about Dvořák is that he came to America, and he most famously wrote the New World Symphony when he lived in New York. So, there’s this whole question: how much did Dvořák influence American music, and how much did American culture affect Dvořák? And I think showing that not some little fragment, but really this whole movement, is based around an American bird that he heard and was inspired by—it speaks to that question. It shows how he was influenced by his environment, especially Spillville, which he loved.

GH: Mark, you mentioned an ecology course at Carleton in the paper. Which class was that, and how was it involved with the research?

MM: That was Population Ecology, and I teach it in the spring. In 1990, I decided to have a lab about counting birds to keep track of what’s happening to bird populations in Nerstrand Big Woods State Park. We’re out there at the crack of dawn every year with my Population Ecology class. The students in the class each listen to recordings and learn four or five birdsongs, and we walk around to the same spots every year. We sit and listen for one minute and count all the birds by their songs.

It was relevant data, because those vireos are the second or third most common bird. We hear them every year, at multiple stops. They’re not rare. I was so aware that those vireos just call and call and call, andthat you never see them. In all those years, I’ve rarely seen one. They’re small, and drab, and fly at the very tippy top of the trees. Scarlet tanagers, on the other hand, are like fire. They show up in a flash, and they’re beautiful. We’ve heard them a few times, but mostly we see them.

To me, that just made it so obvious what really happened to Dvořák. He was hearing that bird, and following, following. And then this brilliant, bright red bird goes by, and this is why he says, it was a red bird! I saw it! Well, he saw ared bird, but that wasn’t the bird that was singing.

GH: In the paper, you talked about Czech language analysis. How did that come into it?

MM: Apparently Dvořák said to his secretary, “I watched this bird for over an hour.” But if you really look up this word, it can mean follow, or track, or trace. So he didn’t necessarily mean he had his eyes on it. And we think he didn’t have his eye on it at all. He caught a glimpse of one bird at the very end. So part of the confusion was just getting the language right.

It turns out, professor of psychology Ken Abrams is a fluent Czech speaker, so I sent him the original Czech text. There’s an official translation, but I wanted somebody else to do it again. He gave me a lot of confidence in the words.

GH: Do either of you think you’ll keep writing interdisciplinary papers like this or working together?

MM: I don’t know, what’s our next project?

DB: Here’s an idea. It’s interdisciplinary but it’s on different topics. Of course, we’re very interested in LGBTQ issues, and also I work in a comprehensive pain clinic. I’ve thought about the prevalence of migraine headaches in the LGBTQ community. The most important thing about that is, it’s not been looked at, so we’re sort of left out of the research populations. That’s something that we could potentially do together.

GH: The idea of bringing gender and sexuality into pain studies sounds really important. I’ve learned at Carleton that Black people and Black women in particular are left out of biomedical research, but I hadn’t thought about sexuality as being another variable that isn’t explored.

DB: We all know plenty about old White dudes, but we need to know more about everyone else.

GH: What do you think the biggest thing you’ve learned from this experience has been?

MM: Other than, I’m married to a brilliant musician?

GH: Well, that’s a good one.

MM: I’ve learned a ton. ButI guess I’d pick the interdisciplinary piece. Like everyone, I’ve got my disciplinary blinders. I’m in biology and ecology, and I’m learning a ton, I’m still publishing. But boy, it was really eye opening to learn how all of these things come together. Not only music, but the history part and the culture part. It was so fun to think about being Czech in the middle of America at the end of the 19th Century and what that must have been like.

DB: I’m gonna just throw this out there. Shocker: knowledge and facts and data are all true, until they’re not. This reinforced that for me.

MM: That’s a really good point, too. The story was basically a set of rumors that were repeated, and repetition led to truth. I’ve made a little collection of people saying, unequivocally, that the scarlet tanager inspired this movement. But all you have to do is trace it to the first person who said that, who himself said, well, it doesn’t fit very well, but OK. But that got repeated and repeated and became truer each time it was repeated, and the equivocation falls away, and then there’s truth.