Student Research Partnership uncovers world of drama during trip abroad

History professor Serena Zabin traveled to Scotland and England this summer with Raine Bernhard ’23 and Margaret De Fer ’24 as part of the trio’s ongoing research project into the life of Hannah Flucker.

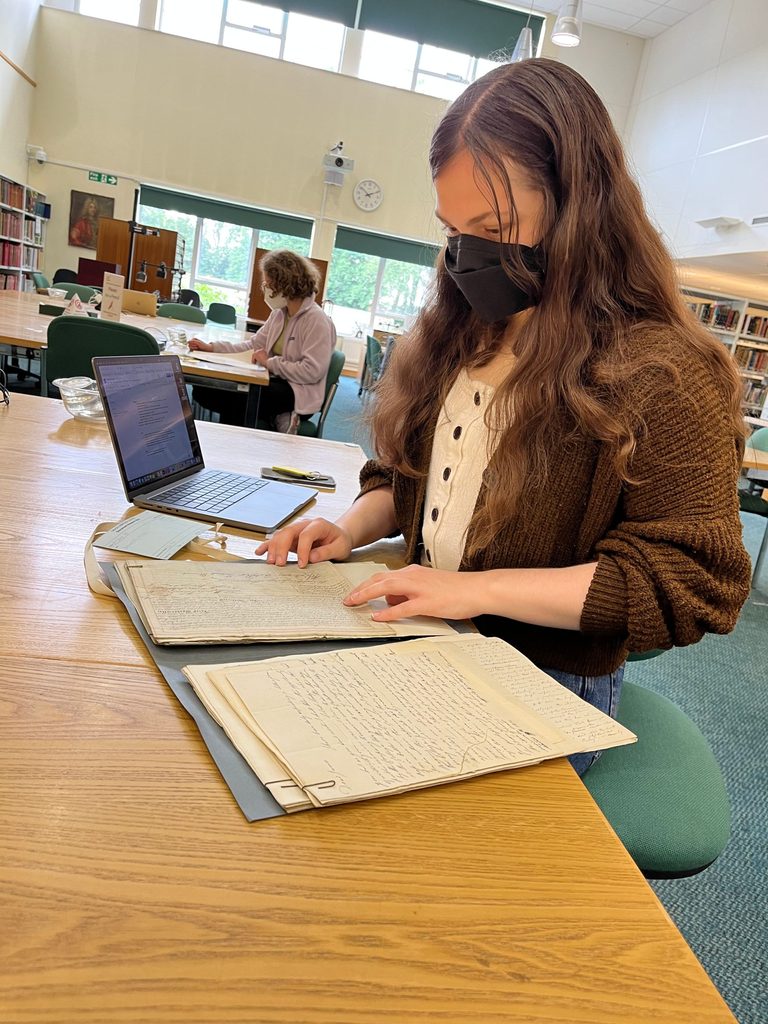

When Professor and Chair of History Serena Zabin and her students, Raine Bernhard ’23 and Margaret De Fer ’24, traveled to Scotland and England this summer, they weren’t expecting to uncover a real-life drama rivaling the plot of a regency romance novel. The purpose of their trip—part of a Student Research Partnership (SRP) through Carleton’s Humanities Center—was to search through legal and national archives for traces of the story of Hannah Flucker, the daughter of a wealthy Boston family who was divorced by Captain James Urquhart, a British army officer, for infidelity in the late 18th century. What they got was much more than just traces.

The story starts well before their summer trip. Zabin, Bernhard and De Fer have been working together on this project for over a year now, although Zabin started it even before that. At the end of her last book, “The Boston Massacre: A Family History,” Zabin wrote about two sisters—Hannah and Lucy Flucker—during the Siege of Boston in 1775. Lucy became an American patriot and married Henry Knox, who ended up as George Washington’s secretary of war. Lucy’s older sister Hannah, on the other hand, married James, who was at that moment the Redcoat officer in charge of the occupied city of Boston. The two sisters never saw each other again after those marriages, which is all Zabin knew about Hannah when she finished her book.

“Historical researchers know a fair amount about Lucy because of her marriage to Henry,” Zabin explained. “There’s a whole world out there of pretty junky scholarship about her, but it’s kind of amazing that people know so little about her sister. Hannah is there by proximity, but no one’s ever paid any attention to that part of the story.”

Zabin decided she would be the one to change that. During the start of the pandemic in 2020, when much of her other work stalled, Zabin began poking around digitized archives online to see if she could find out what happened to Hannah after her marriage to James.

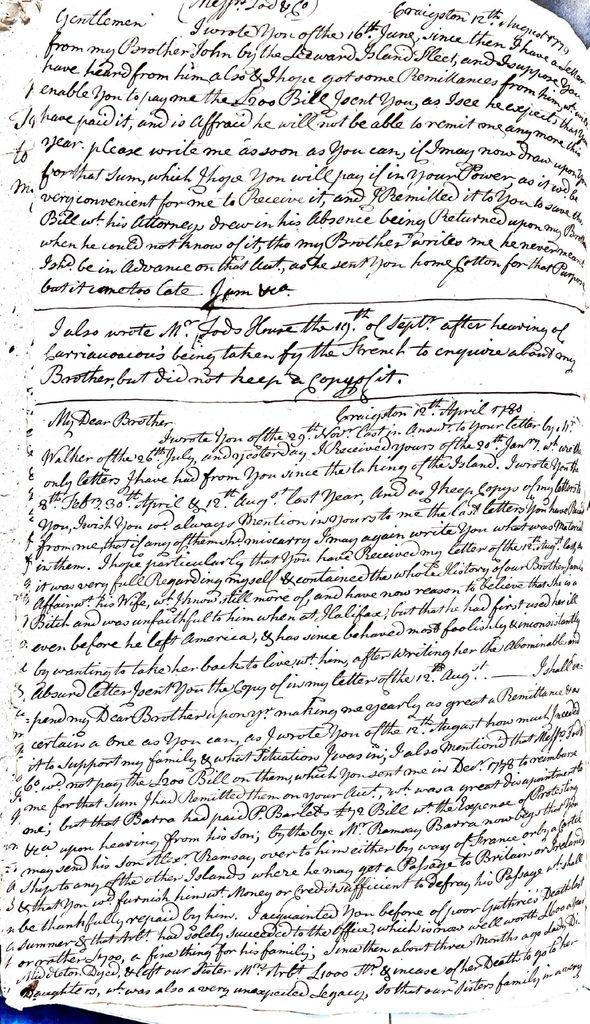

“There had been some hint somewhere that they got a divorce, which I thought was interesting,” she said. “I wrote to the National Archives of Scotland, where James was from, and discovered they had a very full divorce case record with about 150 pages of testimony and summaries, which they scanned and sent to me.”

To help tackle the transcribing of all those documents, Zabin recruited Bernhard and De Fer. Zabin and Bernhard had previously worked together on a different project, and De Fer was already working for the history department and had taken a few of Zabin’s classes.

“The court records turned out to contain this incredibly juicy story in which Hannah—who is only 19 at the start of all this—was accused of having an affair with the marine who brought her from America to London, where she was going to meet James and her father, who had fled Boston with other loyalists,” Zabin said. “The divorce records include depositions from her father’s friends, who were part of this whole world of expatriate Bostonians in London, and they totally threw her under the bus and confirmed she had the affair.”

With every page of the divorce record that Zabin, Bernhard and De Fer transcribed, they became more and more hooked.

“It turns out that Hannah became pregnant by her lover, Stephen Kempe, after which they went to Exeter, England, where she had the baby and Stephen was thrown into debtor’s prison,” Zabin continued. “At that point, they were trying to convince their landlady that they’re actually siblings, and the story just keeps going from there and becomes more and more like a soap opera. Eventually we discovered the baby died, but after that, there’s not much more information in the divorce proceedings.”

Zabin figured they could learn more from the Urquhart family papers, which were stored in the family castle in Scotland and not yet digitized, so she secured an SRP and planned to visit Scotland, London and Exeter—Hannah’s known locations in the UK. In Aberdeen, Scotland, the team discovered a whole cache of letters between Hannah’s brothers- and sisters-in-law, all gossiping about the sordid story.

“One of the most amazing pieces we found was from one of her brothers-in-law,” Zabin said. “At first, he blamed James for the divorce, because James was running through the Flucker family money, but then the brother went to London to pick up some of the more recent gossip. After that, he wrote that Hannah may not have done anything criminal, but it was clear to him that ‘she is a bitch.’ Raine, Margaret and I were in a very silent special collections room in the basement of the University of Aberdeen library, and when we came across that, we let out a huge gasp and disturbed the whole room!”

“We knew that there was some sort of collection of family letters before we went to Aberdeen,” De Fer added, “but we really weren’t expecting the detailed and personality-filled descriptions of everybody’s behavior that we got.”

Bernhard also found that even though Hannah never saw Lucy again after leaving America, they did correspond via letters. Hannah wrote to Henry as well, who at that point was one of the major faces of the new United States. They wrote about familial happenings and drama, of course, but also about business and financial affairs. Mostly they wrote about a very large piece of land—about three counties worth—in Maine that Hannah inherited from her mother, called the Waldo Patent. Hannah worked with Henry from afar to decide what to do with the land.

Hannah and Henry’s positions as co-executors of Mrs. Flucker’s will and their correspondence about the Waldo Patent is what inspired the topic for Bernhard’s comps project this year.

“Henry was already known for taking land in shady, under-the-table ways, particularly up in Maine. Obviously Lucy also inherited a piece of the Waldo Patent, but that became Henry’s automatically because they were married,” Bernhard said. “For my comps, I’ll be looking at how Hannah, in contrast to her sister, ended up retaining control of her part of the land. One of the reasons she could is she had just gotten divorced from James, so there was no husband to take away her control of it.”

One of the main questions Bernhard will be asking in her comps encompasses how women were allowed to own property in the 18th century, with Hannah’s ownership of the Waldo Patent functioning as a test case of sorts.

“She did remarry after James, but she never gave up control of her land,” said Bernhard. “I’ll be investigating the ownership of the Waldo Patent and what it demonstrates about married women owning land in America at that time.”

Bernhard’s project slots in nicely with recent historical research interests, according to Zabin.

“Historians have been really intrigued by this legal fiction that married women couldn’t own land at all back then, although it was a real part of English common law called coverture [women having no legal existence outside of their husbands],” she said. “Raine is also looking at the ways in which the question of women’s rights was reinvigorated at the beginning of the United States with all the language around liberty. This case in particular is also interesting in the wider context of what was happening to other American women’s claims on land at the time, especially loyalist women’s claims, because the United States was looking for every excuse to take that land away.”

The opportunities for new discovery that this comps project will bring is one of the aspects Bernhard is most looking forward to.

“I’m going to be particularly drawing on the letters sent back and forth between Hannah, Lucy and Henry, which have been digitized but never gone through thoroughly,” she said. “It’s very exciting to be one of the first to go in and unearth new information.”

Zabin, Bernhard and De Fer also have ideas for their research beyond Bernhard’s comps.

“My fantasy is these two graduate and turn this research into a pitch for a television show,” Zabin said with a laugh. “I feel like it could be the next ‘Bridgerton.’ There’s so much drama and the documents contain a lot of vivid descriptions of people. I’ve been playing around to see if there’s an academic book in this research, too, but I think something more than that would be very fun. It could even work well as a podcast. It really has potential.”

“My sister is a filmmaker and I’d like to work with her on something in the future,” De Fer added. “It’s obviously a very loose idea right now, but I’m interested in doing something serialized, because it really calls out for that kind of episodic treatment.”

It’s not just about the drama—the trio have grown very close to Hannah throughout their research.

“We came to really like her,” De Fer said. “Not that she doesn’t make mistakes—she makes a lot. But she’s a messy, complicated person and that really comes across in a charismatic way in her letters.”

“Her voice is very distinct, which is great to read when you’ve just been going through old naval records and legal documents,” Bernhard added.

“She’s this flawed heroine who, from our 21st century perspective, feels very ‘Fleabag’-ish,” De Fer concluded. “When you read her letters and see her behavior, it’s hard to villainize her. We’d think, well, that was probably the wrong move, but hey, she’s just a young woman following her heart! We’ve become kind of emotionally attached.”

Zabin, Bernhard and De Fer all agree that reading Hannah’s voice feels extremely relevant to each of them as well. Her perspective is not a relic of a bygone era; instead, it feels universal, reminding Hannah’s researchers that humans in every century have had similar problems.

“We’ve found that this story is poignant and relevant in a modern context in so many ways,” De Fer said. “The actions and emotions of these people resonate with us. The historical aspect of the research is exciting, of course, but it also feels like such a contemporary narrative at the same time.”

The research process itself has become important to Zabin, Bernhard and De Fer, too.

“This has felt like a project that’s needed us,” Zabin said. “Historical records like this—when they even get saved in the first place—are just sitting there, waiting for us to read them. They don’t mean anything until people make meaning out of them. This whole process has felt like Hannah needed us to come and figure out her story, and it’s been very educational and an enormous adventure. This is also the first time I’ve had research assistants who are as fast as I am. Our pandemic year of transcribing manuscripts twice a week made an enormous difference in the research that followed.”

“That year of reading and transcribing was a great experience,” De Fer agreed. “We also got to formulate our own thoughts about the situation as we did all that, which was excellent preparation for interpreting all the information we found during our trip. The time we spent cultivating our expertise before traveling also allowed us to be really productive during our archival searches. I feel like we’re the foremost experts on Hannah Flucker now!”

They certainly are experts, and that knowledge was forged with the help of an incredible amount of collaboration.

“I’ve never shared a research project in this particular way with students,” Zabin said. “It felt pretty non-hierarchical. I had the original idea and planned the trip obviously, but we were all contributing skills and ideas the whole way through. I hadn’t quite anticipated, not only that it would be so much fun, but that we would be three times as efficient as I would have been by myself—which was fortunate, because we had an unusually large number of archival successes.”

Zabin, Bernhard and De Fer’s Student Research Partnership experience was full of impressive discoveries. Whether it results in “the next ‘Bridgerton’” or not, the project has provided the participants with unmatched historical research opportunities.

“I never would have imagined being able to do this kind of research as an undergrad, or even at all, in my life,” De Fer said. “So much of the research you do as a student—which is still very fun—is working with a lot of secondary sources or primary sources that have already been transcribed and heavily interpreted. This project has felt very close to the source in a way that’s really exciting and rare. I’m so grateful that I’ve now had this range of experiences, and I’m only a junior!”

Erica Helgerud ’20 is the news and social media manager for Carleton College.