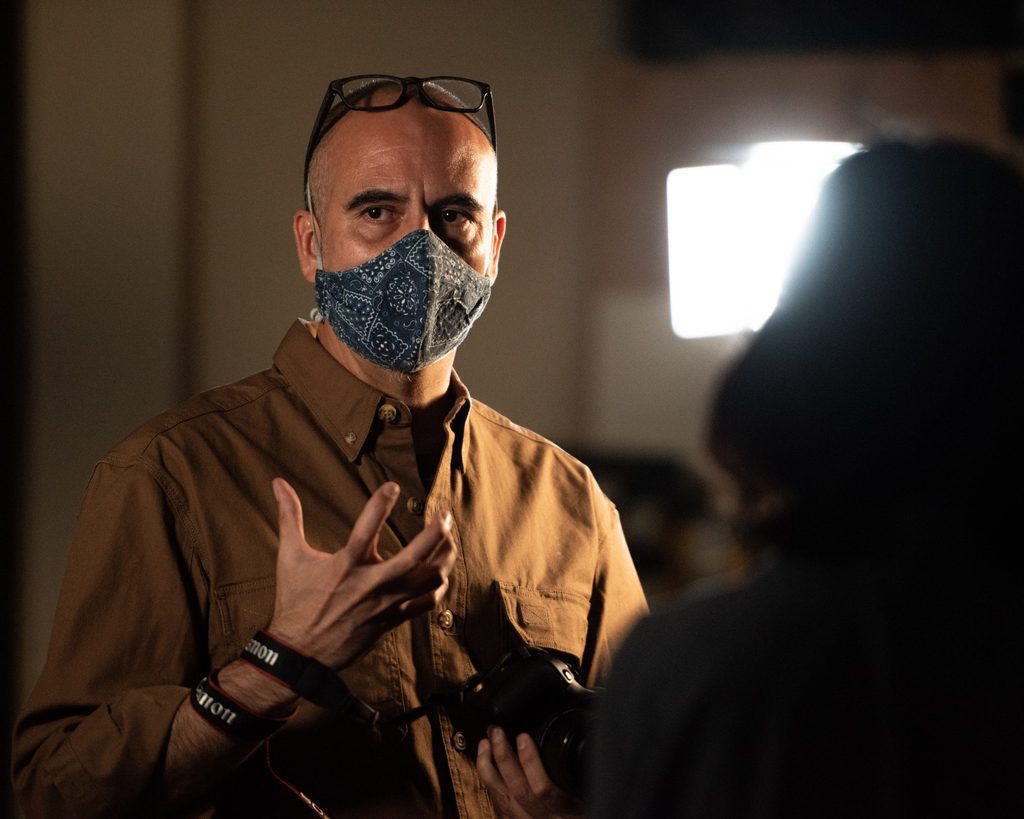

Profiles in Teaching: Xavier Tavera Castro Uses Photography as a Vehicle for Storytelling

Tavera, an assistant art professor who is currently teaching Beginning Photography and Constructed Image, began a permanent faculty position at Carleton this fall.

Xavier Tavera Castro is passionate about using photography as a vehicle for storytelling.

“For me, one of the most important parts of photography is understanding how people situate themselves as image-makers today,” Tavera said. “What does it mean to have a cell phone camera all the time? How do we use it? Why do we document the things that we document?”

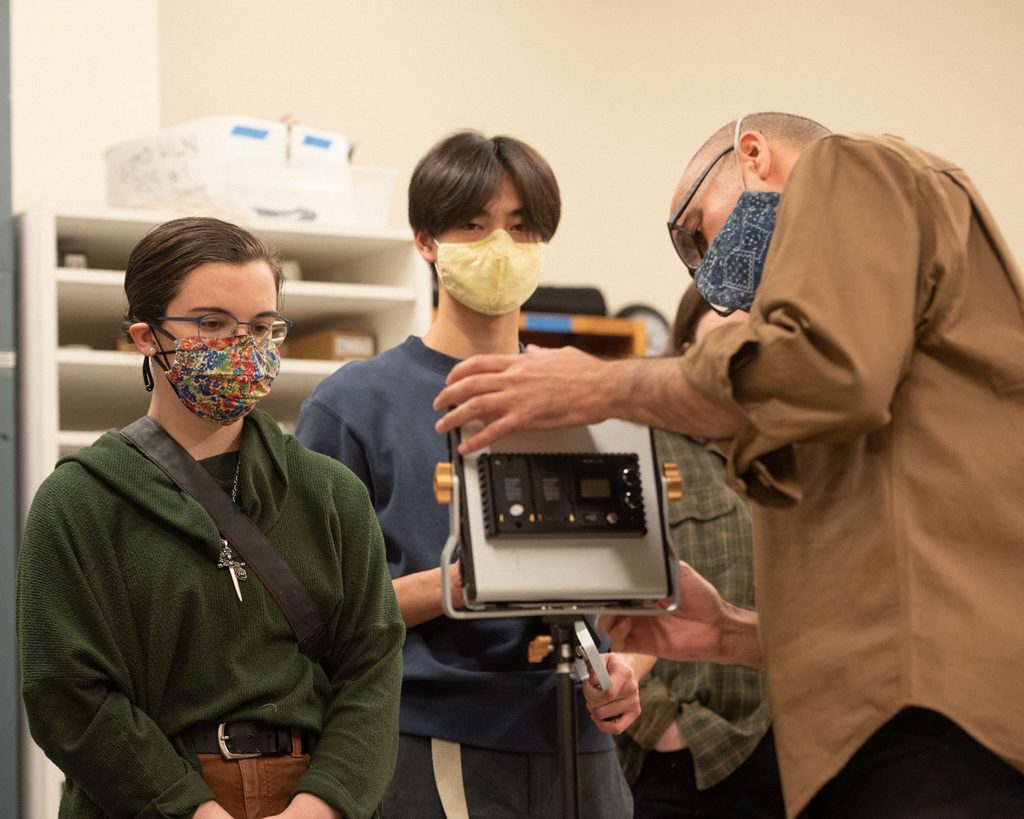

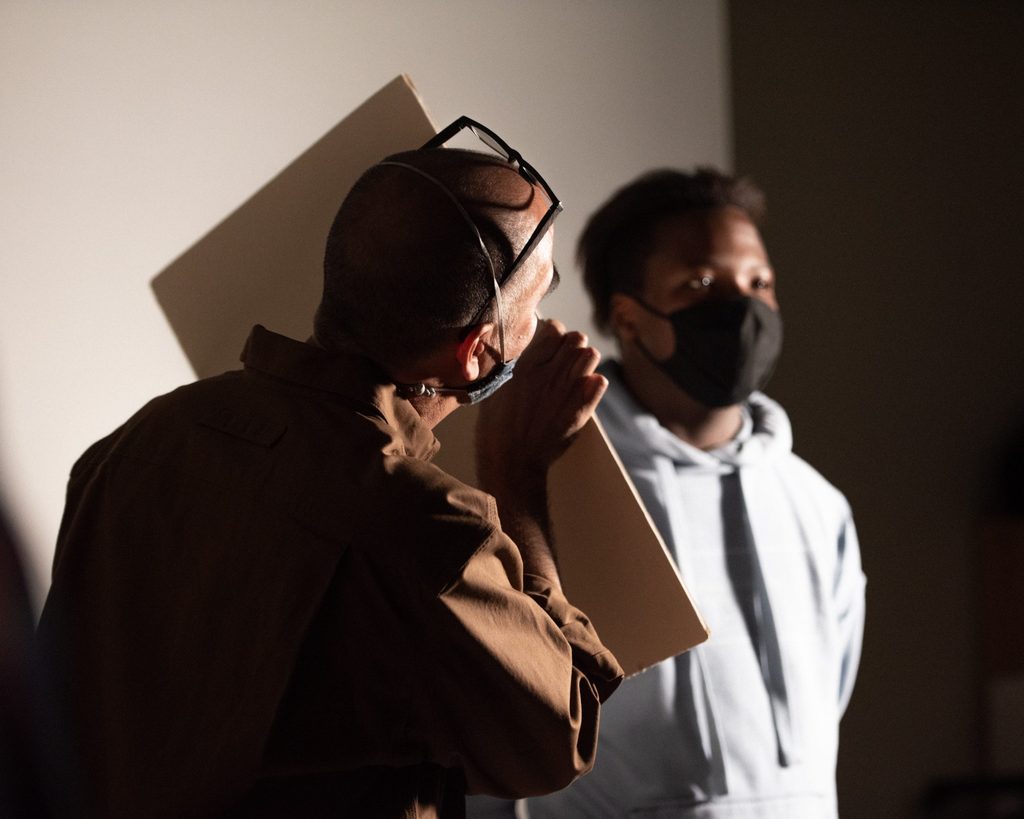

Tavera, an assistant professor who is currently teaching Beginning Photography and Constructed Image, began a permanent faculty position at Carleton this fall. We met on a Wednesday afternoon, soon after he had finished teaching. A few students lingered in the classroom, and I found Tavera bent over an image on his computer, in the midst of a passionate discussion with a student about their artwork. As they finished their conversation, he approached me warmly and invited me to sit.

We began by talking about his time so far at Carleton, and some of his favorite aspects of being at Carleton full time.

“There is an opportunity to see students grow year after year, and not only in photography,” he said. “They might take a ceramics class, or a biology class, and when they come back, there’s a thread [to their growth] that I can follow.”

In his classes, Tavera focuses on the story behind the image. His goal is to create photographers who not only take technically beautiful images, but also thoughtful, meaning-rich ones.

“Historically, we have done horrible things with photography. It has been used as a weapon of colonization, it has been used to diminish people, it has been used as a form of surveillance,” he said. “I want students to acknowledge that type of photography, and then tell their own stories…. What do you have to say with the language of photography?”

Tavera’s ultimate goal in teaching is to connect the art of photography to the wider world.

“I’m in education to attempt to make better citizens of image-making, not to make better students or better image-makers. I want to make students who have empathy for others and respect others’ images,” he said.

Creating Conversation through Photography

“I’ve been photographing since I can remember, probably since around 13 years old,” Tavera said. “Although, according to my mom, I started taking photos at the age of six when I demanded to bring a camera to summer camp.”

“I began taking photography more seriously around 16, and I tried to start a photography business focused on photographing dance and theater troupes,” he added. “In the end, it was a failed endeavor, but I learned a lot through the process. Later on, I discovered that I can use photography as a means of expression, and I went crazy learning about the language and recording powers of image-making.”

In his own work, Tavera finds inspiration in the lives of Latin American immigrants and other communities of Latinx people in the United States. Born in Mexico City, Tavera immigrated to the United States 25 years ago.

“When I moved to the U.S., I shifted my focus around photography completely,” he said. “Because of the lack of representation of the Latinx community here, I decided to focus on this community living in the United States.”

“I try to get a fair representation of who we [the Latinx community in the U.S.] are,” he added.“Of course, that varies, and my work is only from my point of view. A lot of my photography is both documentary and conceptual; I photograph communities as I see them, which doesn’t always match what they might represent to the majority of people.”

One of Tavera’s current projects is curating an upcoming art exhibition that broaches the idea of what it means to be a mixed-race Latinx person in the United States.

“Mestizaje is a word that the Spaniards came up with when they arrived. It’s a colonizing word, and it means mixed. The exhibition asks, ‘What does it mean to be mestizo?’ What does it mean that we are part of two cultures? How do we assimilate that? Repel it? Fight it? There are a lot of questions, and there is a constant fight in our bodies and in our minds,” he said.

The goal of the exhibition is to start a conversation, not to reach a final answer.

“The project has the potential to blow up in our faces,” Tavera said. “We don’t want to come to conclusions or declare ‘This is what mestizaje means.’ We just want to start a conversation and talk about this thing that is constantly evolving.”

The exhibition, titled “Mestizaje: Intermix/Remix” will be shown this spring at the Minnesota Museum of American Art in St. Paul.

Our conversation about the exhibition pivoted briefly into a discussion about public art when Tavera mentioned that the exhibit would be displayed publicly, in the museum’s windows, for passersby to witness.

“Public art brings up the question of what it means to have art out in the world where people don’t have a choice but to stumble upon it,” Tavera said. “It’s different in a gallery, where people are purposefully going there to see art and know that they will be challenged and exposed to new ideas.”