Focus on community guides Carleton summer research trip to Peru

Postdoctoral fellow Dr. Sarah Kennedy, Sophie Baggett ’23, Claire Boyle ’25, Collin Kelso ’25, Ezra Kucur ’25 and Kalju Maegi ’23 spent a month in Puno, Peru studying heavy metal poisoning in soil and interacting with the community affected by it.

Summer research projects allow opportunities for Carleton students and faculty to collaborate on important work outside the classroom. Whether it’s a Student Research Partnership (SRP) through the Humanities Center, one of the many Integrated Math and Science research fellowships or an independent study, Carls participate in a broad spectrum of intellectual undertakings every summer.

This year, Dr. Sarah Kennedy, Robert A. Oden Jr. postdoctoral fellow for innovation in the humanities and archaeology, traveled to Puno, Peru with five Carleton students for her research project entitled “The Ongoing Environmental Impacts of Silver Refining in Peru,” usually referred to by its Spanish acronym PAMA (“Proyecto Arqueológico Medio Ambiente”). Four of the students—Claire Boyle ’25, Collin Kelso ’25, Ezra Kucur ’25 and Kalju Maegi ’23—participated in an SRP and one—Sophie Baggett ’23—was there for an independent student research fellowship. The SRP students conducted archaeological and anthropological fieldwork while Baggett, with her background in Spanish and public health, established goals and guidelines for community interaction.

The PAMA research project, which extends beyond these students’ involvement, was created to assess the ongoing environmental impact of colonial-era silver refining by establishing a rigorous universal survey methodology for the evaluation of heavy metals in soils, waterways and vegetation. The fieldwork is integral to a larger project goal of decolonizing archaeological and anthropological research.

“It is about identifying different methodological tools that we can use to assess heavy metals in archaeological soils,” Kennedy explained, “but we’re also building on work we’ve done previously by establishing stronger community collaborations with Indigenous groups, local Peruvian nonprofits and environmental studies organizations to communicate health risks of these toxic soils and heavy metals to the communities. Our long-term plans are trying to establish more locally-driven initiatives, where Indigenous groups and local people living on and near these archaeological sites are the ones asking the research questions and leading the efforts on how to deal with the heavy metal poisoning.”

Kennedy and her collaborators, Peruvian co-director Karen Durand Cáceres of the Ministry of Culture and Dr. Sarah Kelloway of the University of Sydney, hope that this kind of wide-reaching project will affect the entire field of archaeology.

“We want to convince other people to develop this methodology,” said Kennedy. “It’s relatively low cost and easy to do, and with it, people can test sites prior to working in them, [thereby] hopefully preventing various illnesses that can occur from being exposed to heavy metals. A lot of the people that work at archaeological sites around the world are students, volunteers and Indigenous or local workers. Those are the people that are actually in the dirt and being exposed to the heavy metals, so I think it’s important to emphasize that this isn’t just to protect the small percentage of people who are professional archaeologists in the world. It’s also because we employ a lot of more marginalized groups.”

Because the focus of the project was on methodology and community outreach, the kinds of tasks Kennedy and her students accomplished on their trip were not what one might picture when prompted to think of “archaeological fieldwork.”

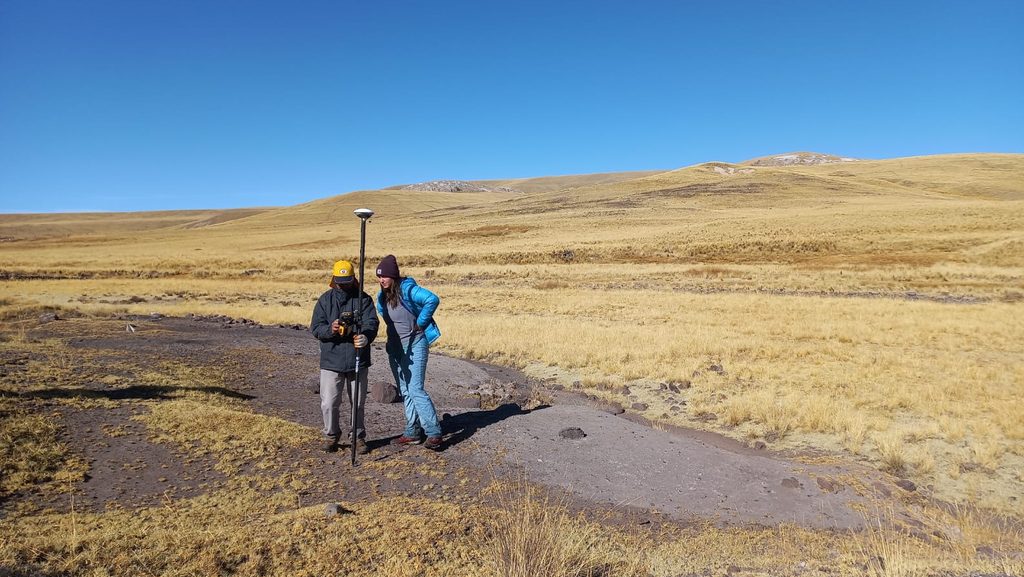

“This was a non-excavation project,” explained Maegi, who is a senior sociology/anthropology major and archaeology minor. “It’s all pXRF [portable X-ray fluorescence] samples of soil, water and vegetation, as well as a lot of site mapping and file establishing, collecting and correcting, which is all digital. It’s not the sort of romantic, ‘Let’s put on our Indiana Jones hat and dig up some pottery and break into people’s tombs to look at mummies’ kind of thing. That’s not happening.”

It may sound less than exciting to some; however, Kennedy and her students reported that there is more to archaeology than digging things up, especially in a place like Puno.

“As a prospective geology major,” said sophomore student Kelso, “I’m very into nature and there is no shortage of natural beauty at these sites. At one mesa site we went to, we could see the entirety of this giant basin, probably many tens of miles across. The vista was huge and just beautiful. It’s definitely romantic in that regard, even though we aren’t doing any digging or picking up artifacts.”

Maegi agreed and added, “I had to pinch myself sometimes. I was on top of a mesa the other day in a pre-Inca [Colla] city, looking down at Lake Umayo, which is directly adjacent to Lake Titicaca, just 20 miles away. It was one of the most gorgeous views I’ve ever seen in my life. As someone who grew up in Minneapolis, I’m not used to mountains. I was like, ‘I’m here right now? This is real?’ It was incredible.”

Peru’s striking scenery was a constant in the Carls’ day-to-day as they alternated between field and lab work throughout the week.

“In the field, we typically divided into smaller teams to work on tasks,” said Boyle, another sophomore, “which included laying grids for site surveys, flagging buildings or other areas of interest, collecting water and vegetation samples, using the Trimble GPS [data collection hardware] to map the site or record the locations of samples and using the pXRF to take soil measurements.”

“For site visits, we had early wake-ups at 5:30 or 6 a.m. depending on the distance to the site,” added Kucur, also a sophomore. “Our closest site was a 20-minute car drive and our furthest was an hour drive and then an hour hike up a mesa.”

When the students weren’t in the field, they performed lab work, which involved labeling plant or ceramic samples, correcting Trimble GPS data and digital file work. Lab duties also included working with Baggett, a senior biology major also minoring in Spanish, whose independent fellowship served the community outreach aspect of the project goals. Her job was ultimately to determine the most effective ways to communicate the research team’s results once they obtained them.

“I interviewed site landowners, NGO employees and government officials to determine both community knowledge about and current practices for disseminating information about heavy metals,” Baggett said. “Sometimes I traveled with the team to the archaeological sites, where I spoke with landowners with the help of an Aymara speaker and local archaeologist, Roger [Carazas Losa]. Our long-term goal is to use what we learned this year to widely distribute the results of Sarah’s archaeological studies and present our findings of best practices working with the community.”

The field and lab work were positive experiences for the students, with each of them emphasizing a combination of the beautiful surroundings and the people they interacted with.

“Getting to work in the landscape of the altiplano in Peru was really an incredible experience,” said Boyle. “Even in winter, its natural beauty is truly impressive and I really appreciate spending time there. I also loved getting to work and live with our team. Not only have I gotten to know our other Carleton team members much better, but we also had the opportunity to work with Australian and Peruvian archaeologists and students.”

“The landscape and architecture of the sites where we worked was beautiful,” Kucur added, “and being able to spend long periods of time there allowed us to really explore each site. I also enjoyed getting to know new people and working with other students from all over the world. The community that we created in Peru was amazing.”

A favorite aspect of this kinship creation for Baggett was “‘family dinners,’ the weeknight meals where we gathered as a team and shared about the day’s work while trying Peruvian dishes.” The local food was a standout from the trip—the granadilla, a sweet, aromatic fruit, was Kelso’s favorite—with the language and travel opportunities also noted as exceptional.

“The immersion was amazing,” said Kelso. “I feel like Puno is not that unlike my home city of New York, except everyone speaks Spanish and it’s a different culture. It was very interesting and so cool to be able to experience life as you would in Peru—as much as a gringo can, anyway. We also did our fair share of exploring around the city and neighboring areas like Arequipa, Taquile Island and Cutimbo [a pre-Inca Lupaca archaeology site].”

“I would say the same thing, especially as someone who hasn’t been afforded too many opportunities to travel in my life,” Maegi said. “I was fortunate enough to see family in Estonia when I was younger, and Carleton gave me a grant to conduct archaeological research in Portugal last year, but while those places are very different from the U.S. in many ways, I never really experienced true culture shock. Whereas walking down the street in Puno, just seeing all these different colors and buildings that you’re not used to, smelling all the smells and eating all the food, there’s not a whole lot that is visibly cosmopolitan or especially Western. It’s distinct from what I conceive of as familiar, which has been very valuable, especially in terms of skill-building, like learning the language and navigating both cultural unfamiliarities and literal physical streets.”

This experience will certainly affect the rest of their Carleton careers, especially because three out of the five participating students are rising sophomores with plenty of time left on campus.

“I came into this trip already wanting to be an archaeology minor,” Kucur said, “so this experience has only strengthened that desire. I took an archaeology class every term last year and I’m taking another in the fall.”

“This trip has enhanced my understanding and experience in fields I was previously interested in,” added Boyle. “I am especially grateful for the way this project combined archaeology with geology, as that is likely my chosen course of study at Carleton.”

Similar to Boyle, Kelso’s interests also lie in both geology and archaeology.

“This gave me the opportunity to do an archaeological field study while also building skills that will be very useful in geology going forward, like mass spectrometry, GPS data, file correction and that sort of thing,” Kelso said. “This is also quite an interdisciplinary trip, as most of [the SRP trips] are, I think. We’ve got an intersection of public health, geology and archaeology. It’s very ‘Carleton.’”

For Maegi and Baggett, as seniors, the trip enriched their already-established majors and minors and cemented a passion for travel. Maegi, due to his credit distribution as a transfer student, only has one term left—naturally, he’ll be spending it overseas.

“Puno is topographically, climatically, linguistically and culturally not proximate to what is familiar to me and that’s why I love to travel,” he said. “That’s why I want to continue to travel, to expose myself to that unfamiliarity, [so] I’m going to Morocco for my study abroad as my last term as a Carl. After that, I’ve applied to teach English in Spain starting next January and I’m also in the process of applying for a Fulbright that would begin fall of 2023, which is exciting. My plans are certainly foreign-oriented!”

Kennedy’s summer research project has been very fulfilling for her students. They encourage other Carls to take advantage of all their available opportunities, whether it’s an SRP over the summer, an Off-Campus Studies (OCS) program during term or a fellowship after they leave Carleton.

“We’re getting essentially an all-expenses-paid trip except meals to come and work in Peru for a month,” Maegi said. “Who wouldn’t want to do that? If something like this is attractive to you, don’t be afraid to go for it, especially if money is the problem. There are so many opportunities at this little college in Northfield, Minnesota of all places that can take you almost anywhere. Ask people in the fellowship office, people in OCS and your professors what resources they have for you, because they do have them… And that’s what this liberal arts education is all about, right?”

Faculty interested in applying for next year’s Student Research Partnerships should direct any questions to Clara Hardy. Students interested in participating should inform their professors whose research they find intriguing. For all non-SRP fellowship information, visit the Office of Student Fellowships.

Erica Helgerud ’20 is the news and social media manager for Carleton College.