Comps Insider: Maddie Fry’s ‘Bringing a Friend Along’

Sociology and anthropology major Maddie Fry ’22 explored philanthropy and community life in Northfield for their comps project.

Why do individuals engage in altruism? What, exactly, motivates us to act selflessly for the greater good? Philosophically, we may never see a definitive answer. But when sociology and anthropology (SOAN) major Maddie Fry ’22 framed the question in the context of Northfield’s Community Action Center (CAC), they developed a clearer picture: an uplifting snapshot of how a small town responds to an enormous problem and a challenge to the notion of philanthropy itself.

Fry initially came to SOAN amid uncertainty.

“I thought I was going to [major in] religion,” they recount, “then I thought I was going to be bio and then poli sci, and then finally—like, right before the deadline—I landed on SOAN.”

Despite hesitant beginnings, they soon became dedicated to the discipline.

“It’s an amazing major with an incredible group of professors,” Fry says, and it has “completely reshaped the way I think about the world… It has made me reconsider how important relationships are in terms of community building but also in terms of self-building… People can’t be individuals without conducting themselves in relation to others.”

Fry encountered the theme of community relationships firsthand when they began working with the organization that would inspire their comps. As a junior, they took Anthropology of Health and Illness, an Academic Civic Engagement (ACE) course culminating in a civic engagement project. Amidst the onset of COVID-19, Fry explains, the CAC was “restructuring their entire program” while “working with more clients than ever before.” Fry’s project—interviewing clients about their experience with the CAC—concluded after that course, but they continued working with the CAC for the rest of the year. Fry soon became curious not only about the clients but the donors. Their question was twofold: First, “Why are people… giving their money to a nonprofit in Northfield, a small town, during a pandemic?” and second, “How are people looking at themselves as donors?”

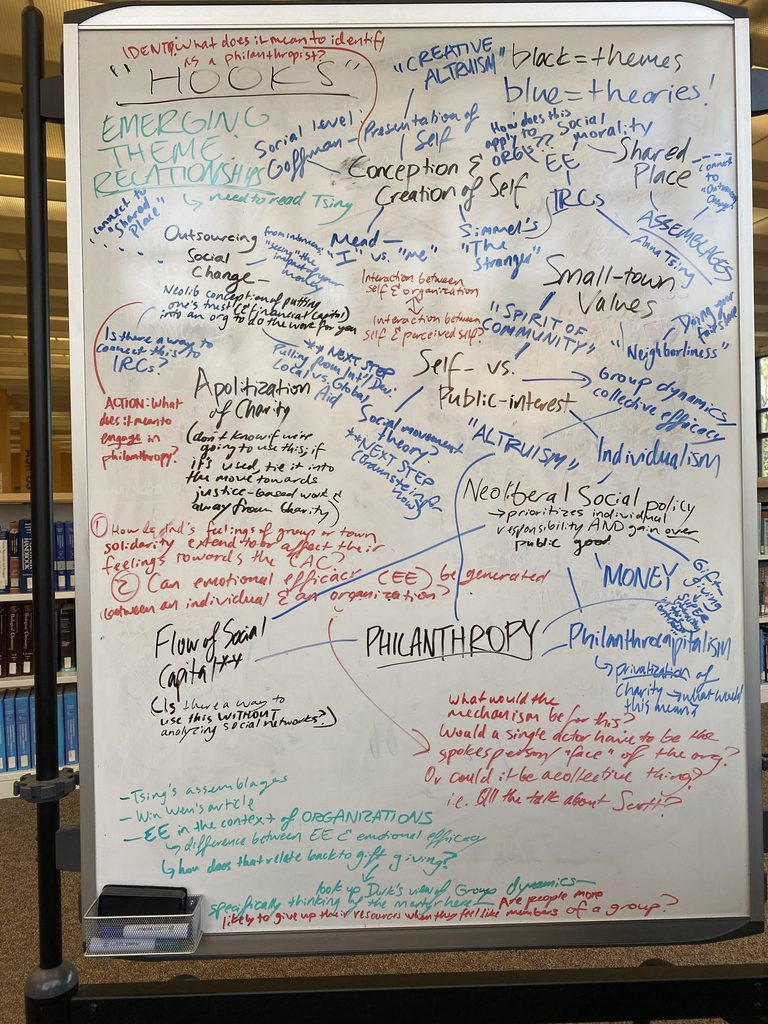

Sociological theory informed much of Fry’s early approach to the question. As sociologists understand it, philanthropy consists of “this ‘benevolent other’ giving to those less fortunate,” Fry says. Thus, charities take a “one-way” approach to big donors that Fry summarizes as: “You give us money, we give you gratitude.”

There was also the concept of “collective efficacy,” an “idea in neighborhood studies that people living together in small spaces have the ability to collectively solve social issues,” Fry explains. In a tiny town like Northfield, social ties would be strong enough that citizens “have the agency to come together… instead of having to have somebody come and solve problems for them.”

However, Fry’s findings contrasted starkly with the field’s understandings. For instance, the donors did not appear to subscribe to the traditional definition of philanthropy. Rather than faraway strangers, “these clients were neighbors, they were friends, they were community members.” Rather than theatrical defenders of the disadvantaged, “nobody said ‘client,’ nobody said the word ‘charity’ either.” And rather than seeking publicity and broad-scale gratitude, “they subscribe to the idea of being a good neighbor” and participate in “the discourse of what it means to be part of Northfield.”

Furthermore, while the donors believed in banding together as a neighborhood around a common cause, their precise reasons for chipping in proved nuanced. Of Fry’s ten interviewees, those closer to the upper middle class stated that donating is “a morally right thing to do and [they] would be wrong for not doing it.” At the same time, those skewing more working class said they donated because they could “easily put [themselves] in the shoes of the people currently using the CAC services.”

After consulting with their advisor and CAC colleagues, Fry gravitated away from theory and towards their interviewees’ experiences.

“It was really important not to let the theories that I was reading run away with my work,” Fry says. “There’s this idea in sociology that instead of starting with a theory and then using your interviews and data to prove it, you go into your interviews, find an idea that is surprising, and then go back to the theory and wed those together.”

As it turned out, the donors’ unexpected attitudes toward charitable giving and their diverse reasons for it shared significant commonalities.

If there was one factor that “caused this discourse about being a good Northfielder,” Fry says, it was COVID-19, which every interviewee cited as a moral awakening. After all, the pandemic is not exclusive to those already marginalized. According to Fry, “COVID has impacted everyone and has positioned the middle class much more precariously… Everyone is on edge now.”

Yet rather than inciting panic and selfishness, for Fry’s interviewees, the virus “has started moving people away from thinking about philanthropy in a transactional way… It’s creating much more of a two-way, community-centric, solidarity-driven movement.” More than ever, Northfielders are aware of “what money means and [of] the power associated with donating.” Their contributions display belief in the moral necessity of neighborliness and empathy for economic instability. Ironically, Fry’s findings linked back to sociological theory after all: They exemplify Simmelian solidarity, “a short-term but sustained sense that we are, across class boundaries, all in this together.”

On a broader scale, Fry’s research indicates that philanthropy might be more complex than we currently understand.

“Philanthropy is a label that can and should apply to everyone, but the fact that it is only applied to and reserved for the rich has a particular political resonance,” Fry says. “What I’m trying to argue in my comps is that there’s a way to reclaim that… I suggested a new label called ‘everyday philanthropy’ that better explains this type of donating—everyday people giving money in smaller amounts than the uber-rich giving at a Bill Gates level.”

Fry did not expect to find these results when they began their research.

“I’m just bombarded a lot of the time with the ‘bad’ about Northfield. I went into [my comps] with this chip on my shoulder,” Fry says, “and I was pleasantly surprised in all my conversations about how people saw themselves and their community.”

While COVID may be temporary, Fry theorizes that “with the right discourse, with the right narratives, with the right words,” Northfield’s newfound neighborliness may be here to stay. “I think people just have to be convinced,” they conclude.

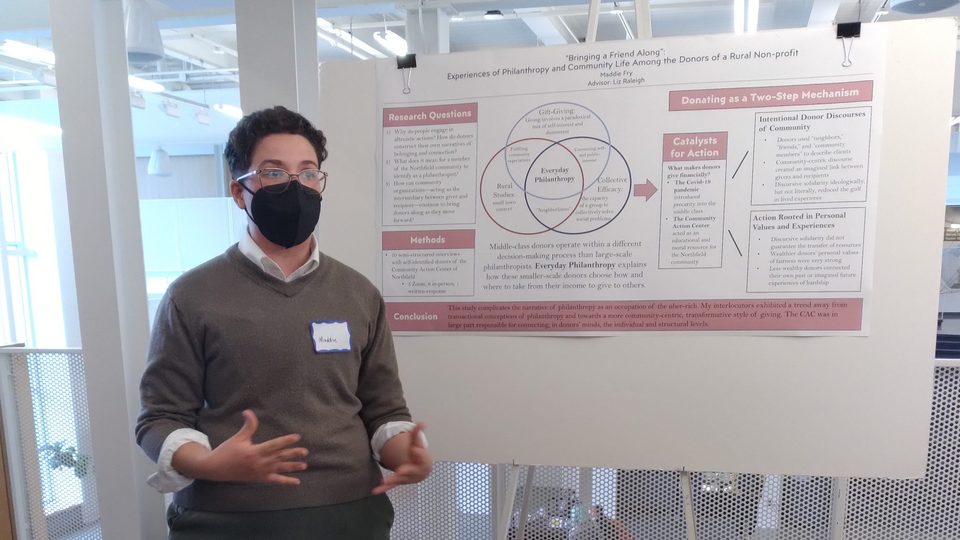

Fry presented their comps, titled “Bringing a Friend Along: Experiences of Philanthropy and Community Life Among the Donors of a Rural Non-profit,” at the SOAN comps presentation session in April. While they have since graduated, they will remain at Carleton as the Center for Community and Civic Engagement’s (CCCE) fifth year education associate and plan to continue working with the CAC. They would like to thank their advisor Liz Raleigh, their CAC colleagues and the other SOAN seniors for their support.