“Black at Carleton, 1966-1979” Explores the Legacy of Black Students from a Different Generation

The exhibit, which was on display for Black History Month, is a collaboration between the Student Activities Office (SAO) and the Office of Intercultural Life (OIL) that started as an art history project by Jevon Robinson, a senior from New York.

A sign in the center of “Black at Carleton” describes the exhibit as an “an homage to those who came before and the legacy they left behind.”

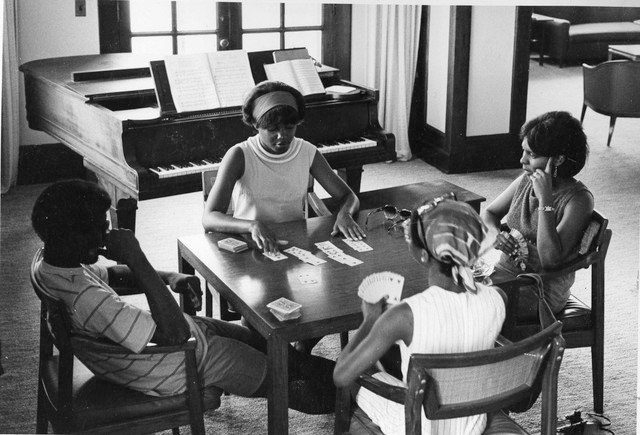

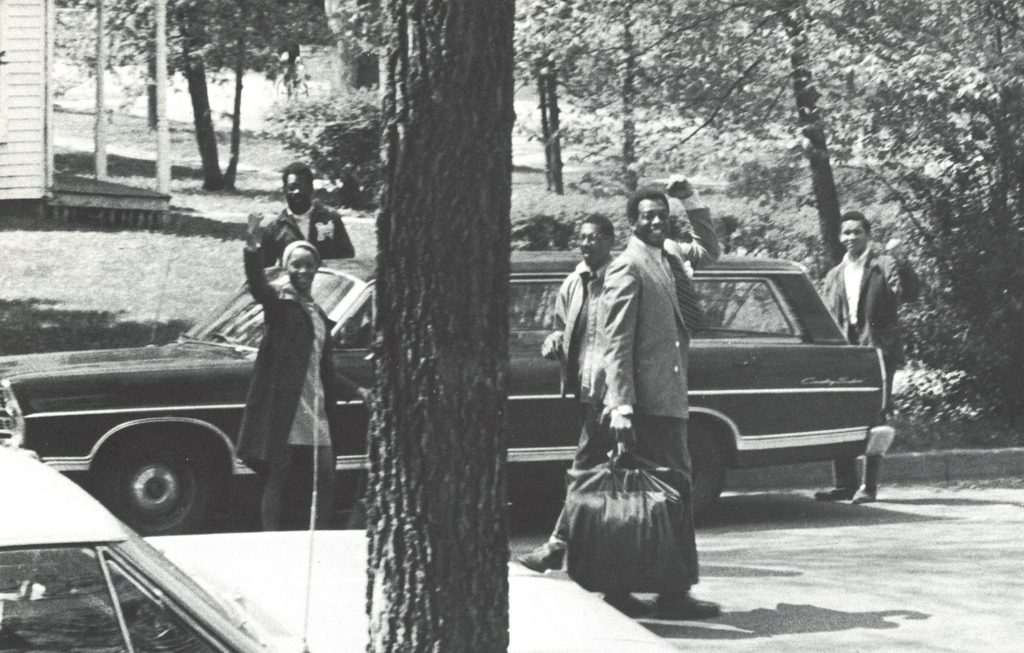

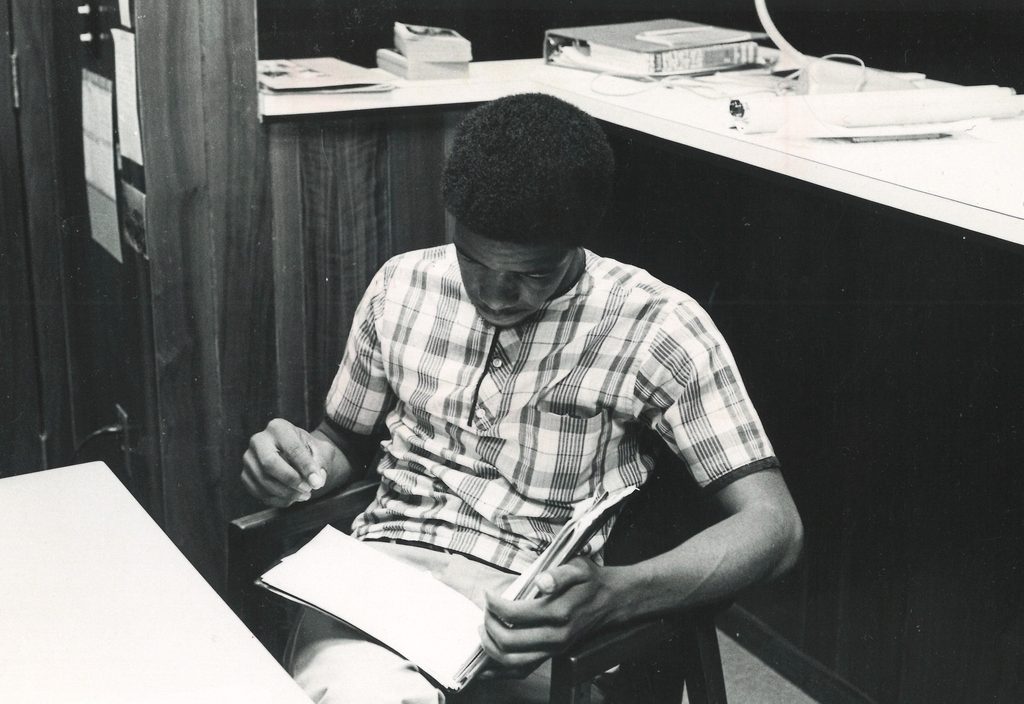

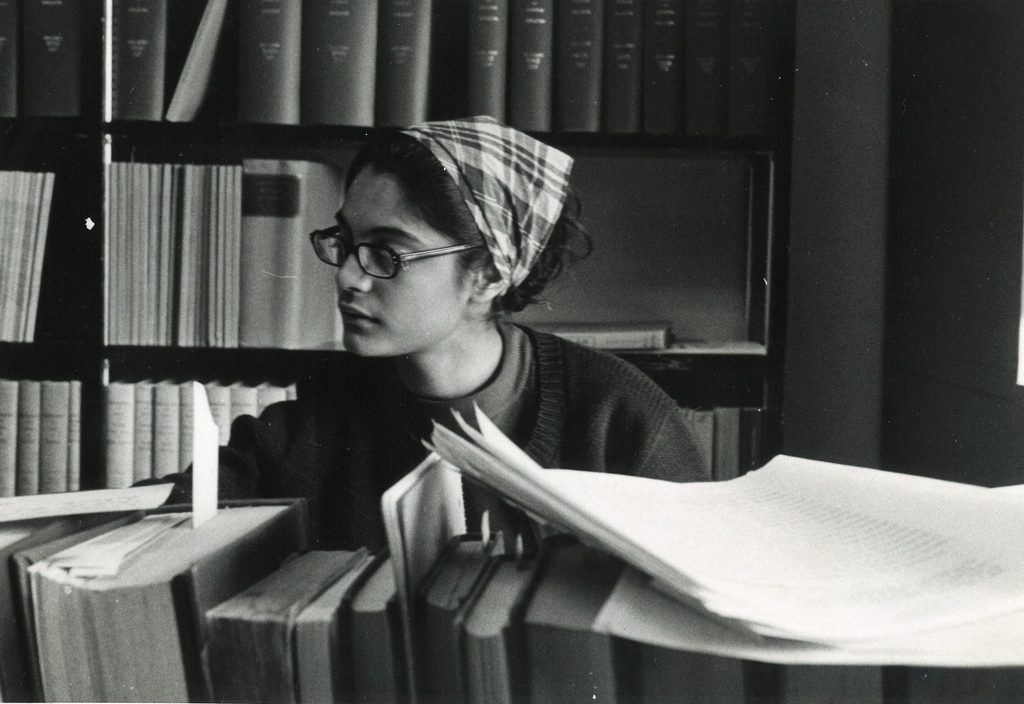

Delving into the exhibit reveals the lasting impact of that legacy. Beyond students’ huge lapels and wide-legged pants, the exhibit’s snapshot of Black students’ life from the 1960s and 1970s will look familiar to students today. Students hung out and studied in Black House, organized and wrote letters to the administration, and participated in literary magazines and dance companies. But as the exhibit tells us, these are spaces that Black students once had to fight for.

Located in Upper Sayles throughout the month of February, “Black at Carleton” is a collaboration between the Student Activities Office (SAO) and the Office of Intercultural Life (OIL) that started as an art history project by Jevon Robinson, a senior from New York. After learning that the first multicultural house at Carleton was established at Hill House in the 1960s, Robinson went to the archives to see what records of the house were available. “There were photos of Black students being themselves in the space, and just coming across those pictures is really rare to see in the archives,” he said. From there, Robinson presented the photos to OIL Director Renee Faulkner, who began to explore the idea of creating an exhibit for Black History Month.

“It started out with Black House, but then we found a lot of great pictures from Ebony II, which was the Black dance company,” Faulkner said. “Everything, we pulled from the archives.”

Tom Lamb, one of two college archivists, worked with Faulkner and her team of students, who he described spending many hours poring over materials.

“We tried to find things that were interesting but also told discrete stories about what was going on at the time,” Faulkner said.

One such story is Black student organizing on campus. On display are several documents from SOUL, the Black student organization on campus at the time, such as internal memos and correspondence with President John Nason. Much of the organizing centered on Carleton’s promise to increase the Black student population to 10%.

“The College had made these promises, but the Black students didn’t feel like there was enough progress being made,” Faulkner said. “They had a list of demands, there were protests organized, rallies organized, petitions. And it was successful to an extent. There hadn’t been any Black admissions officers, and then there was. There hadn’t been any Africana or Black Studies program, and then there was. So the organizing that they did at this time paid off in a lot of ways that we still benefit from now.”

Faulkner and Robinson connected SOUL’s organizing to recent activism on campus, particularly the Ujamaa Collective and Carls Talk Back.

“Black students organized, they came together around some common concerns, and they made those concerns known, and they stuck with it until they saw some action, which is very similar to what we’re seeing now with the Ujamaa Collective,” Faulkner said.

Student organizing also helped to establish Black House. In the mid-1960s, Black students sent a request to Residential Life for a Black-interest house, which was approved. “But President Nason was not exactly thrilled about the idea at the time, and you can tell by the tone of the correspondence,” Robinson said.

Quickly, Black House became an institution on Carleton’s campus. In a 1973 Carletonian article, a Black House resident describes the house as: “a place where we may come together, discuss, and through unity, find a ‘raison d’etre’ and identity on a predominantly white campus.”

“It’s interesting to consider [Black House] in conjunction with the upcoming housing plan,” Robinson added. “They’re about to build new cultural spaces, and [the exhibit] adds to the reasoning and context behind the plan.”

Beyond organizing, Black students’ creative outlets at the time also left a big legacy. Several photos show performances by Ebony II, which later became Synchrony II, Carleton’s largest dance group.

“Back then, it was a way to create space for Black students,” Robinson said. “Today, when we have campus tours, you don’t really hear about stuff that’s catered to Black students, which is OK, but at the same time, there are a few things that exist today [like Synchrony] which had a completely different context.”

In addition to its rich content, the exhibit provided a meaningful way for current Black students to connect with alumni.

“Black students are looking for that insight and perspective from those who came before,” Faulkner said. “What is this place, and what does this mean for me?”

Robinson described a recent meeting with Toni Carter ’75, a Ramsey County Commissioner who presented Carleton’s convocation address earlier this month.

“We were looking at the exhibit, and she was like, ‘I think that’s me!'” Robinson said. “Then I showed her the rest of the pictures on my laptop, and she pointed herself out, and told people’s names and whether they were still alive. I didn’t even know she was in the pictures until after the convocation.”

Faulkner noted that plans are in the works to create a virtual version of the exhibit, which alumni will be able to access.

“We’re getting a lot of requests from people who aren’t close by who can’t come see it,” she said. “I think it’ll be great because you’ll be able to see the exhibit in its space and click in and see the things that we weren’t able to fit physically in the space. And if folks are looking at it, hopefully they can help us identify who’s in the pictures.”

Lamb also shared plans to solicit archives from the Multicultural Alumni Network, which will meet on campus this fall.

Next term, the Black House archives will be included in a wider exhibit on the history of Carleton’s campus. “Imagined Futures, Forgotten Pasts” will be available in the Perlman Teaching Museum beginning April 1.

For Faulkner, she hopes to continue find creative ways to showcase the experiences of people of color.

“There are lessons to be learned,” she said. “With opportunities like this, you can look at the past and see what was effective, whether that be protest tactics or how Black students were able to create their own space and create a sense of belonging.”