Biology professor Amanda Hund ’10 brings largest-ever faculty grant to Carleton

Hund will lead a network of students, scientists and artists on a multi-year project to study parasitic disease transmission and its ecological and evolutionary factors, as well as communicate the findings in creative and informative ways.

What is a helminth and why does it matter?

The first question is easy; it’s a parasitic worm. The second question is part of what Visiting Research Assistant Professor of Biology Amanda Hund ’10 will help tackle as the principal investigator (PI) of a massive new grant from the Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases (EEID) program of the National Science Foundation (NSF)—the largest grant a single Carleton faculty member has ever gotten for their individual scholarship.

“Amanda’s grant is unique in terms of its size,” Associate Director of the Grants Office Charlotte Whited said. “While we’ve received larger grants, they have been for larger, college-wide initiatives and have involved more faculty, staff and students.”

Photo by Dan Bolnick.

Hund’s multi-year project, “Linking Ecology, Behavior, and Immunology to Spatio-Temporal Variation in Helminth Transmission,” is a collaborative effort with researchers from the University of Connecticut, the University of Wisconsin Madison, the University of California Davis, the Biodiversity Research Institute and the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre. The NSF grant will fund every aspect of their work—the research itself, lab experiments, and everything that goes into collecting and analyzing the data; the creation of a modeling toolkit to measure transmission patterns across space and time that will also be applicable to other projects; multiple undergraduate research experiences, such as summer and winter break research positions; an interdisciplinary undergraduate class on the research topic to be taught multiple times over the course of the project; a high school science program, with teaching materials made broadly available through published lesson plans; and an art-science collaboration involving Indigenous artists and a science journalism student to produce a traveling exhibition and website focused on the project.

The scale needed to complete everything is extensive, hence the multiple institutions working on the project with Hund. That collaboration will not only benefit the research, it will give Carleton students a number of incredible opportunities.

“We’re connecting Carleton to this big team of researchers, and our students will get to be part of field teams, exchange programs, annual project meetings and more,” Hund said. “That’s one of the reasons this grant is so exciting, because we’re forming this collaborative network headed by Carleton.”

Carleton also happens to be the only small liberal arts college in the group. The grant is even specifically designated by the NSF as one for Research at an Undergraduate Institution (RUI), which provides another layer of support for researchers and for students. Hund’s proposal included an extra set of documents to explain how the grant would impact a place like Carleton.

“We’ve thought a lot about what we’re going to do with the project in terms of its broader impact and in terms of teaching,” Hund said. “We’re actively working to connect our research and the science to students and the wider community.”

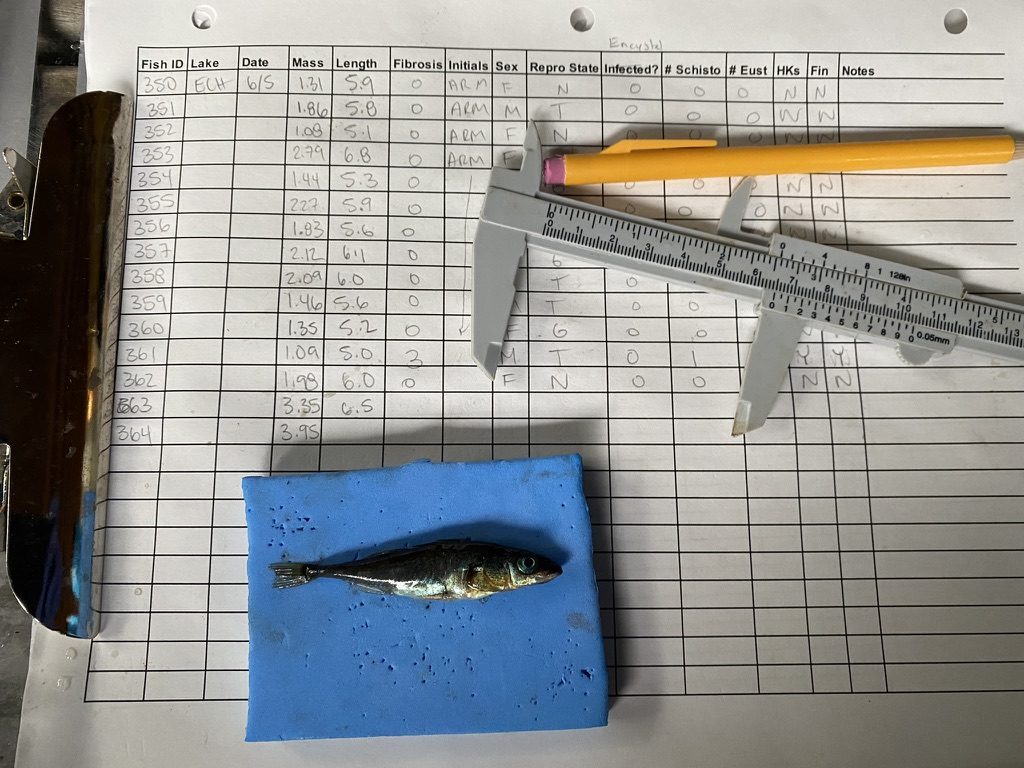

Photo by Amanda Hund.

At the center of every piece of their research is S. solidus, a type of helminth which will serve as a test case to study disease transmission and the ecological and evolutionary factors that influence it. Historically, S. solidus has primarily only been studied in sticklebacks—a type of lake fish—which is just one stage of their complex life cycle. Host species also include birds and small crustaceans called copepods. When a bird eats a fish with S. solidus, the helminth moves into the bird to reproduce. The S. solidus eggs are then passed by the bird before they hatch and find their way into copepods. Fish eat the copepods, and the cycle starts again.

Interestingly, previous data on S. solidus in sticklebacks have shown a wide range of variation when it comes to this type of helminth, seemingly dependent on their geographical location—some lakes have no S. solidus in their fish, some are teeming with it; some S. solidus specimens are huge, some are tiny. Figuring out the “why” behind these changing data points is a major motivator for Hund’s research, as what she and her collaborators learn will hopefully be important to understanding not only S. solidus transmission but parasite transmission of many kinds.

“There are important gaps in our understanding of how diseases move across landscapes and why populations differ in how infected they are. This is especially true for the transmission of multihost parasites,” Hund said. “Helminths have also been under-researched compared to other diseases, even though they are still a huge problem for people and livestock around the world. We’re hoping what we learn and the models we create for measuring differences and patterns across space, time, and host species will help us answer important basic questions about disease ecology and inform further research to help humans and livestock directly.”

To help communicate what they find, Hund and her team will form partnerships with First Nations artists from Vancouver Island, Canada—their primary site for field work—with Carleton students leading the charge in identifying and reaching out to those who might be interested and a good fit. The artists will join Hund’s team in the field to experience the science first hand before creating art that will communicate it in an informative and interesting way.

“The idea is that art and science are both ways of observing, understanding and translating the natural world,” Hund said. “The First Nations artists also have a long history of living in this landscape, so they’ll bring that knowledge to the scientific visualizations as well as their creative interpretations of the research. Our collaboration will enrich all of our experiences.”

For Hund, the link between science and art is a clear and historical one.

“After scientists observe a phenomenon and draw conclusions about it, we generally try to communicate our findings to an audience by taking complexity and simplifying it to portray meaning,” Hund said. “The process of art is very similar. Artists observe their environment and translate it into a representative work for other people. The first naturalists really functioned as artists too, using drawings to understand and record what they found. Field drawings and book illustrations were hugely influential in early biology, so I’m excited to have this project exist in a similar space.”

Photo by Dan Bolnick.

Hund and the other scientists, students and artists will work together to create some kind of exhibition at the end of the grant term that brings together all the data and art—right now, “exhibition” is loosely defined on purpose, so the team can see where the project goes and what will need to be included in the final product. The team will focus on representing how art and science understand the natural world and how they can collaborate to understand it better, with the hope that the unique format will bring their findings to audiences who may not seek scientific information out on their own.

The exhibition will tour after it’s completed, starting on Vancouver Island and moving to each of the institutions participating in the grant. Every piece of content—including scientific resources, interviews with the team, photos of the research process and the art—will also be available on a website, put together by a science journalism graduate student from the University of Connecticut, so people who aren’t on one of the member campuses can see and interact with everything. The website will also host the high school curriculum the team will create, in order to allow non-local students to engage with the teaching materials in addition to the school districts close to Carleton and the other participating institutions.

Teaching is a major consideration of the project, especially due to the RUI designation from the NSF. At Carleton, Hund will begin offering a biology course next year focused on the kind of disease ecology her project tackles. The lab for that course will give students the opportunity to participate in collecting actual data for the larger research project, as they will dissect fish caught in the field, perform DNA extraction, identify parasites and help analyze other real samples and data from Hund’s research team.

“With this course, more Carleton students will get to be part of the ongoing science,” Hund said. “Each year the course is offered it might look a bit different, but the general focus will stay on helminths and disease ecology. The course will also connect the research to broader issues in society, especially how helminths affect human health and livestock.”

Some Carls will also get to participate in the research as summer interns or winter or spring break assistants, helping Hund with her work on Vancouver Island and in the labs of the other participating institutions. The students will work with every aspect of the project in order to see the whole process at various stages—catching and tagging loons, dissecting sticklebacks, extracting DNA, modeling mathematical data and more. Hund is hoping to also use the winter and spring break times to send students to stay at the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre to gain experience sampling and performing experiments.

Photo by Dan Bolnick.

“Kind of like an exchange program, students will be able to go work on this research for a summer or winter break at another institution and be co-mentored by one of our collaborators,” Hund said. “These connections will provide such a breadth of experience for Carls interested in scientific research.”

Through the exchanges, undergraduate courses and exhibit work, Hund will be able to involve scores more students than she would if she could only take on a few students per summer lab session. Students will also get the chance to be true team members, with Hund planning for opportunities to present at annual meetings and help plan next steps for the project.

“There will be a lot of different aspects for students to get involved in,” Hund said, “whether that’s a single student learning a bunch of different things or a bunch of students being able to come in and learn something specific they’re interested in.”

Hund is especially excited about the potential of this project to help Carls learn more about their post-graduation options.

“Because Carleton is solely an undergraduate institution, our students often fill the role of what a grad student would do in a lot of projects,” Hund said, “which is fantastic experience, but it does mean they don’t really interact with grad students. This project will give them the opportunity to receive mentorship from someone a bit closer to them in age and life experience, and get the chance to ask them all their questions.”

Not interested in graduate school? No problem—Hund’s team is full of non-academics who students can tap for information and future connections.

“Our network will also show Carleton students that grad school isn’t the only option,” Hund said. “The Biodiversity Research Institute is a nonprofit that does a lot of conservation work, for example, and we’ll be interacting with their staff scientists and field technicians. There are many paths they can take to do what they’re interested in.”

As the grant gets off the ground and all its positive outcomes begin to be realized, Hund is still reeling from the news that she got funded in the first place.

“I really thought applying for this grant was just going to be a great learning experience,” Hund said with a laugh. “I figured I would get good feedback from the comments and it would help me write my next grant proposal. Honestly, I thought the chance of it getting funding was very small, so I was extremely excited when I found out that we got it. It still hasn’t really sunk in yet!”

No small part of her surprise is the rare nature of a grant like Hund’s being housed at a school like Carleton. Her project is only the fifth time the NSF’s EEID program has funded one of its kind with a PI from an undergraduate institution at its head.

“I’m just so glad the NSF agreed with us that a project like this can and should happen at a small liberal arts college with undergraduates,” Hund said. “Hosting such a big, collaborative, long-term project offers so many opportunities to connect Carleton and our students to other institutions and to the broader impacts of this really important research.”

Erica Helgerud ’20 is the news and social media manager for Carleton College.