2023 Festival de Cammes brings ‘Color of Life’ to Carleton

This year’s Festival de Cammes presented a kaleidoscope of perspectives for viewers to gain insight into the lives and creative projects of Carleton students.

On March 11, the efforts of cinema and media studies (CAMS) majors culminated in the 2023 Festival de Cammes: Color of Life as Adrian Balvuena ’24, Jimmy Bice ’23, David Espinoza ’23, Molly Furlong ’23, Yumo Lu ’23, Astrid Malter ’23, Isaac Crown Manesis ’23, Nikki Marsh ’23, Scout Riley ’23, Jackson Stinebaugh ’23 and Bahar Tas ’23 displayed their work at a film screening in the Weitz Center for Creativity.

Snapshots of each short film compiled in the festival trailer alluded to the varied works the students had to offer. The collection of titles further captured the diversity of themes depicted in the films: “3 Phone Calls,” “a la turca,” “Boys in the Sun,” “Mi Vecina, La Llorona,” “Striking Out ‘Pilot,’” “Stupid Little Place,” “The Sixth Borough,” “Valley Fever,” “Memorial,” “Where Does The Train Go?” and “Who is living in my father’s house?”

This piece aims to offer a picture of this diversity by providing insight into a selection of these works. While far from extensive, consider this a snapshot taken with the camera shutter on slow speed, capturing some of the 2023 Festival de Cammes for those who were unable to join last term.

Boys in the Sun by Adrian Balvuena ’24

When embarking on this exploration, Balvuena’s film provides a beautiful place to start. “Boys in the Sun” is a queer coming-of-age story that “warps the spatial and temporal timeline of their romantic experiences to tell the story of this young couple.” Following two college students reeling from their recent breakup, the viewer moves with them through the present and past as the boys “relive and remember a time when they were inseparable.” A painful yet formative journey that many have gone through and that many have yet to take, Balvuena presents the specifics of this love story to get at the universal feelings of “nostalgia, regret and longing.”

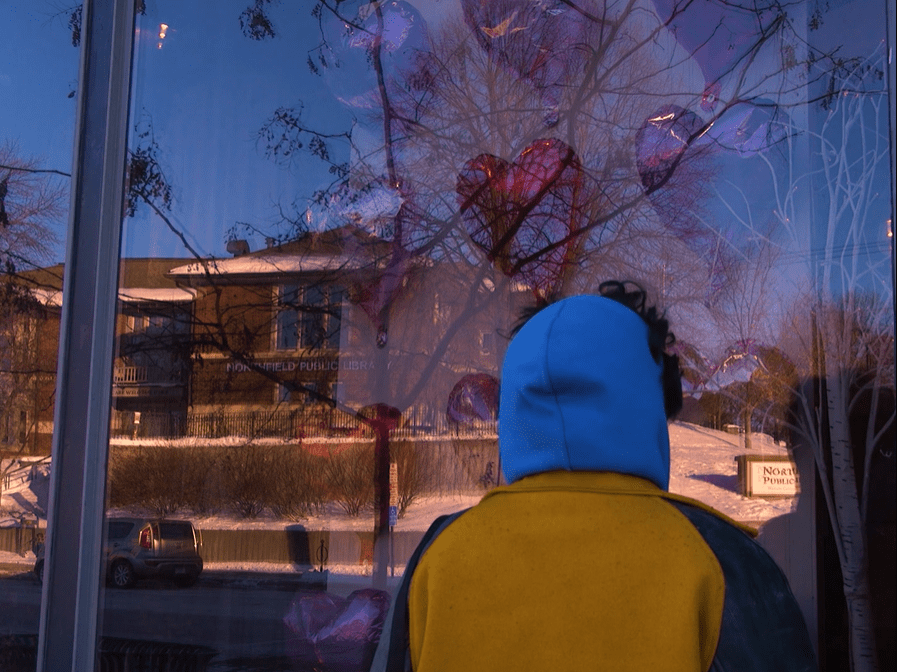

Two boys in the snow open “Boys in the Sun.” Words uttered softly match the muted sky as the camera pans down to the source of the hurt but unhesitant words: “I don’t think you deserve it anymore.” The viewer enters this story at an ending as Leo and Alonso break up on a snowy bridge—recognizable as one of the many that span the Cannon River in Northfield. Balvuena spends the next ten-odd minutes straddling the past and future, from the end of Leo and Alonso’s love to the beginning of the next season of their lives.

Match on action cuts, where the action of one shot matches the continuation of a similar action in the next, fill the short film as it oscillates between past and present. For example, Alonso walks down the bridge, off the screen and away from Leo after the breakup, and in the following shot, the couple walks into the scene, holding hands and peering into a Valentine’s Day storefront display.

Balvuena also uses lighting to impact the tone of each scene, be it nostalgic memory or bitter present. While snowy weather fills every frame, lighting is used to tinge it either blue, cold and lonely, or warm and cozy. In the blue present, Leo is left alone on the bridge after the breakup. Clips of conversations shared between the boys are audible while the visual stays on Leo looking longingly out over the water. The camera cuts to his face, hands and eyes, capturing the physical cues of the emotional effect of remembered words. The camera doesn’t shy away from the discomfort of suddenly being alone. Unwaveringly, it captures the silhouette of Leo sitting by himself on a bench, his profile turning to take in the empty seat beside him.

The abrupt motion of snow hitting a jacket propels the viewer into the next scene, where a snowball fight evolves into the classic romantic scene of the couple falling into each other’s arms. An extreme close up frames a smile, hands scooping snow, a flying snowball. The rosy memory and punchy action jolts the viewer in the same way a jilted lover is jolted with heartache when overcome by a past painful memory.

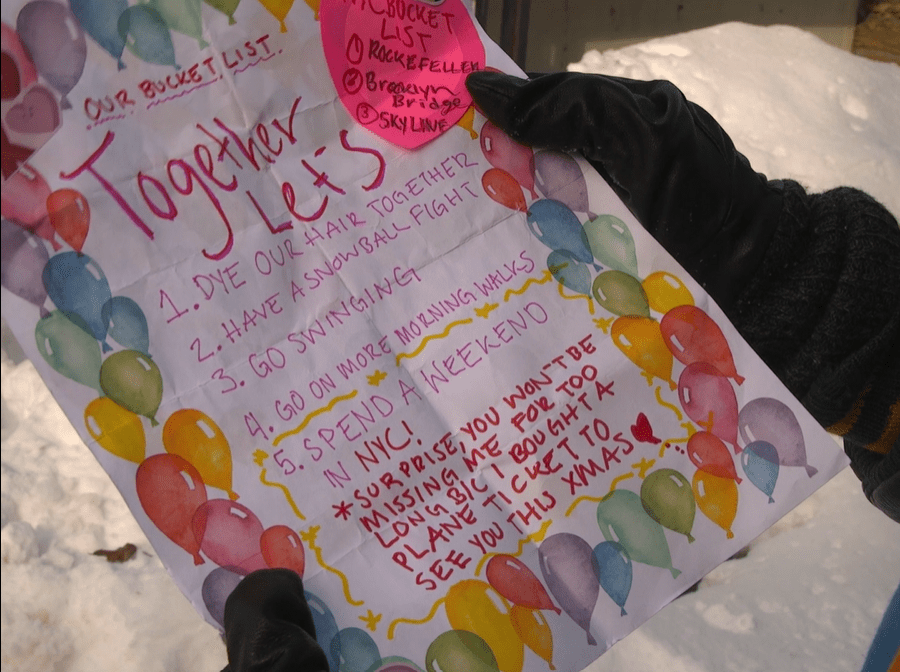

Fracturing the happy memories often with asynchronous sound editing, the film constantly draws the viewer back to the lonely end: the argument. One flashback shares the moment Alonso first made a couple’s bucket list and gifted it to Leo.

“Together let’s… One: dye our hair together. Two: have a snowball fight. Three: go swinging. Four: go on more morning walks. Five: spend a weekend in NYC,” he says. The sound of the scene extends into the next shot of Leo alone, showing how the memory lingers into the present as the camera lingers on the mourning etched in Leo’s downcast eyes and somber expression.

A confession of love from Alonso stated earlier in the film now echoes into the present day, as we hear him lovingly talk about his boyfriend over the film’s final shots: Leo navigating New York City alone. Alonso’s heartfelt “I like your eyes—it’s always your eyes” plays as the camera cuts to Leo’s eyes in the city they were supposed to explore together. Leo takes in the Christmas lights, towering skyscrapers, an indifferent crowd. Alonso’s confession of love is drowned out by the noise in New York City getting louder and louder. Life moves on.

3 Phone Calls by Jimmy Bice ’23

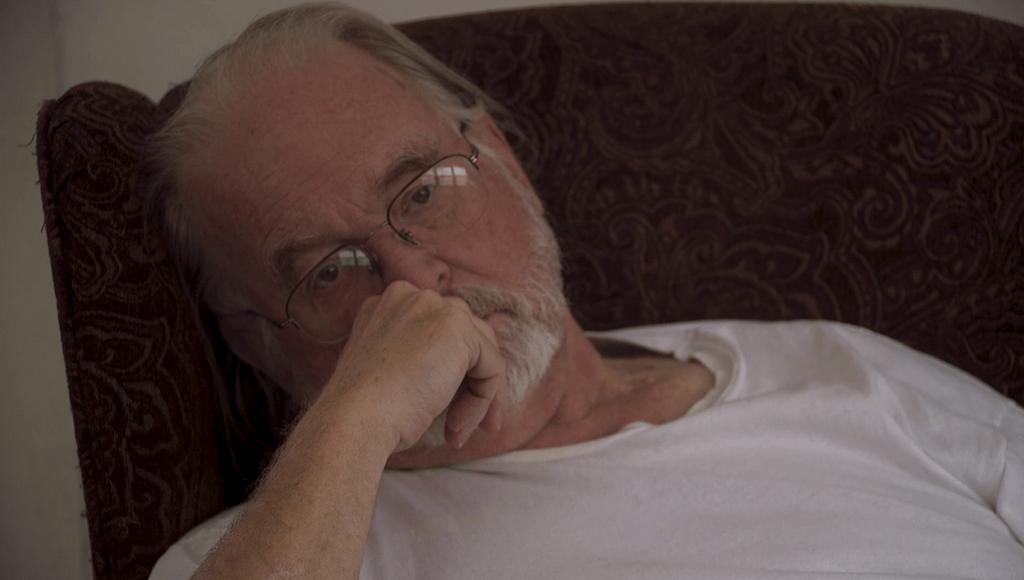

Bice offers a different insight into the world of the Carleton community. He focuses on the parent of a college student in his film “3 Phone Calls,” following John Whitmann, a man suffering from chronic pain, as he “navigates the medical system along with his relationship with his daughter.”

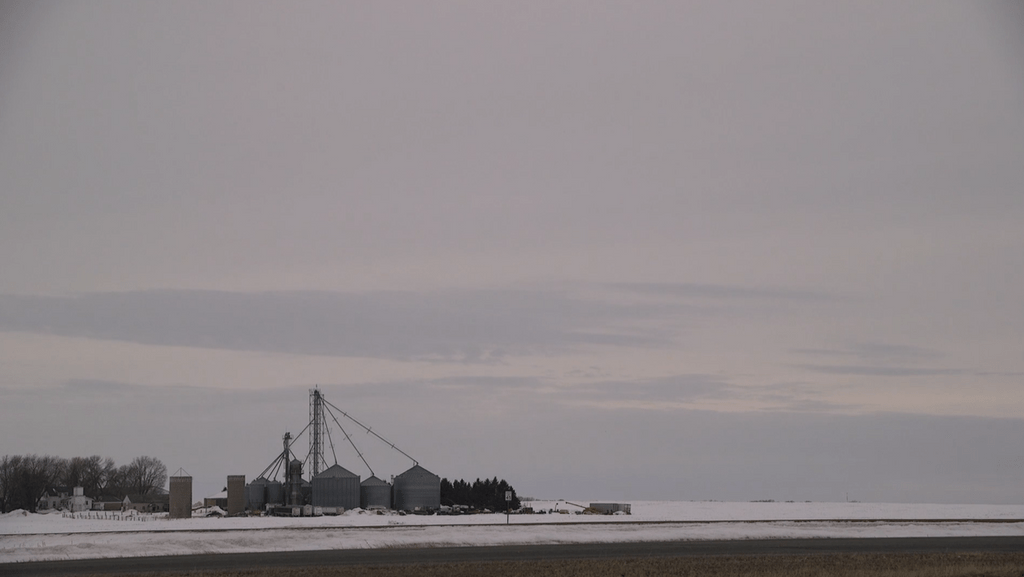

The short film opens with John calling to confirm a telehealth appointment, dialogue full of mounting tension as the secretary cuts off John’s genuine greeting with an insincere “Okay great!” and moving along with impersonal screening questions. The secretary also calls into question the accuracy of John’s self-reported pain rating, brushes him off and ends the call. Bice then cuts to an extra wide shot of a desolate winter Minnesota landscape, accentuating the dismissive emotions evoked by the call.

John’s second phone call is from his daughter, whose bright and bubbly speech vividly contrasts the distant demeanor of the previous interaction. As the conversation turns to John’s awaited MRI results, the two share a heated exchange on the reliability of John’s doctor, with John defending the man and his daughter accusing him of “leading [her father] along on a string.” John cuts his daughter off and insists she doesn’t need to worry about him. This conversation challenges the expected relationship between father and daughter. Tradition would have the father looking out for his child, but as she grows up, the balance shifts, and each must figure out how to navigate the change in their own way.

As John ends the call, the screen fades again into a blustery, lonely Minnesotan landscape. Thin white lines of snowy fields along the bottom of the screen ground a gray sky, cloudy and dark, with industrial farming architecture rising in the middle ground. The sounds of a blustery wind chill the atmosphere even further.

John is next jolted awake by the film’s final phone call, struggling to answer but eventually connecting with his doctor. After explaining that John’s MRI records have been lost and patronizingly questioning him about whether John even went to the MRI, the doctor off-handedly mentions that a hard copy of the records may have been given to him as a disc. John rushes to locate it.

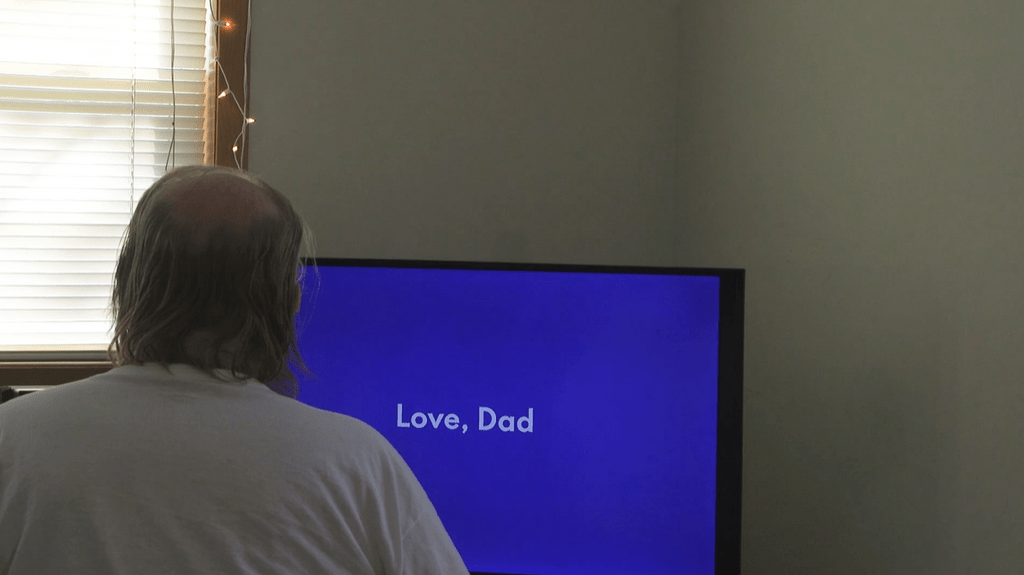

When at last he finds a DVD, what fills his television screen is not MRI results but his daughter’s middle school graduation tape from 2012. Photos of her from over the years fade in and out as the viewer watches John’s daughter grow up from over his shoulder. The video ends with a simple “Love, Dad” in white text on a blue screen. Nothing about it is particularly aesthetically unique—its beauty is found instead in the love that clearly went into its creation. Bice’s film fades to black as we see John, head bowed, reflecting on his day.

“3 Phone Calls” highlights the evolving parent-child relationship that most college students experience, while also calling attention to the difficulty of accessing healthcare in the United States. A moving depiction of a daughter growing up and her dad growing older, we see the life of a college student as shaped by her father’s.

Stupid Little Place by Molly Furlong ’23

Furlong offers their perspective through a short documentary about living in Northfield titled “Stupid Little Place,” which opens with a director voiceover.

“Four years ago, I decided to attend a small liberal arts college in Northfield, Minnesota,” Furlong says in the film. “It’s called Carleton. Ever since then, I’ve been thinking about my place at Carleton and Carleton’s place in Northfield. Some nice people did interviews to help me figure some stuff out.”

Furlong captures the “interesting dynamic between Carleton students—the people who are here temporarily—and Northfield residents—the people who are here all the time,” through a series of open, laid-back interviews. The audience is introduced to the first interviewee with the question: “What’s your name and what level of Pokemon are you at?”

“My name’s Ben [Palm, custodian], I’m level 44 and I work at Burton,” is the laughter-filled response.

Furlong’s other interviewees then introduce themselves. Suhani Thandi ’23, psychology major and educational studies minor, goes next. Contractor Pete Lee says, “You’ll get tangents.” “I did” appears onscreen in response to that aside, displaying the comfortable, playful demeanor with which Furlong conducted the interviews. Ann Beimers ’23, computer science major, grew up in Northfield “since I was seven.” George Zuccolotto works at Blue Monday and on the Northfield City Council. Miguel Hernandez works at El Triunfo.

The interviewees, varying in age, gender, occupation and more, had an array of thoughtful, humorous, delightful and thought-provoking insights. Ben comments on how “in the books” students are at Carleton, and Pete has observed a certain level of “intelligence and curiosity” from everyone on campus. Ann provides a student perspective on the dichotomy between Carleton and Northfield.

“There’s so much I love about Carleton,” she says. “I definitely also have my gripes. I understand why a lot of community members in Northfield feel Carleton is… mysterious and closed off. The outgoingness of standard Northfield residents definitely contrasts with standard Carleton students. Maybe those things come into conflict in a way.”

Suhani also talks about this relationship, speaking from her unique experience having spent two summers in Northfield during the height of COVID-19. This perspective opened her eyes to the world beyond campus and how Northfield transforms without students in town.

“The fact that there weren’t students around forced me to see Northfield,” Suhani says. “We live in Northfield, technically, that’s our address, but really we live on campus.”

Suhani’s interview provides Furlong’s film with its title, as she concludes, “Wow, I kinda do like this stupid little place.” It was, however, a journey for her to become content with the small town. “It took me a really long time to appreciate Northfield coming from a big city,” she says, “I kind of hated it at first.” Suhani grew to value the close-knit community unique to Northfield, though, where “people are super helpful. They want to do things for you, they want to help you.”

George expanded on the friendly community found in Northfield that some Carleton students seem hesitant to engage with.

“Why do so many Carleton students seem so afraid and nervous all the time?” he asks Furlong in the film. “No one is going to hurt you, at least not here. People will really help you out. Ask and don’t be afraid to give without asking. Walk an old lady across the street and ask them their name. Or talk to your local barista. Just having those conversations with people and letting those relationships grow could be super valuable to the Carleton community.”

Ultimately, George encouraged the Carleton student body to “be aware that there are cool things where you are at, in the time and space where you are living.”

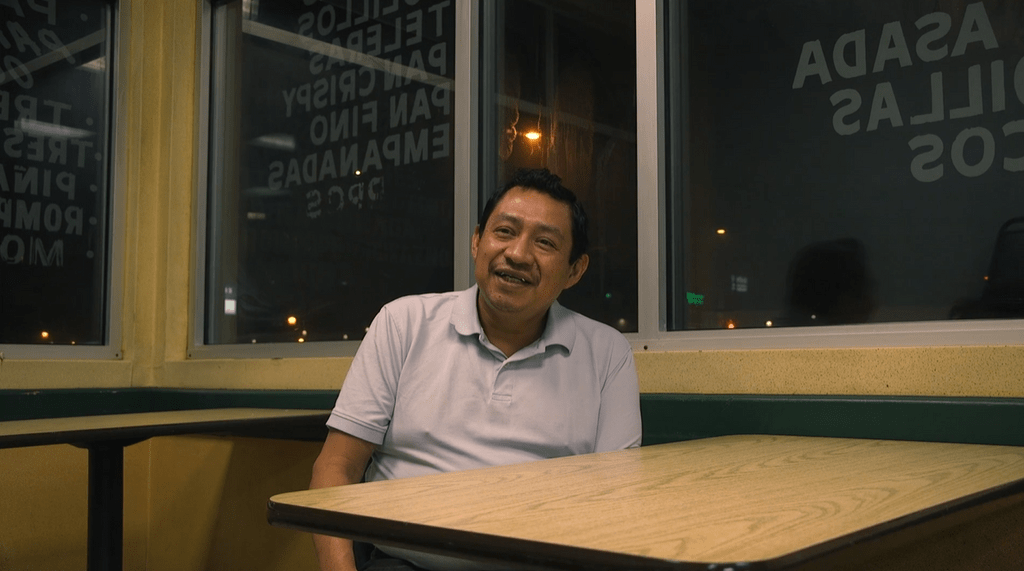

Miguel, the final interviewee, ties together the loose ends created by this assortment of perspectives. Working with a translator to speak with Furlong, Miguel is a testament to the helpful nature of the Northfield community as he describes his experience with Carleton students. Starting as an outsider himself, “I came here out of necessity,” he says. “My parents went bankrupt and we had to immigrate.” Miguel has since grown his business—the beloved local restaurant El Triunfo—and uses food to connect with students, going the extra mile to welcome and bring comfort to anyone who visits it.

“I have told them that whatever they need, I am here to help, always,” he says. “I have helped young people that I see sometimes, who aren’t eating. They’re in a group, and one isn’t eating. I go and bring them, at the very least, two tacos. So they can join the group. God has blessed me with that role. I would like for students to know I would do the same for them. Because I have a daughter who’s also a student, if i do something for someone, someone will do it for my daughter, too. That’s my mentality.”

This connection, facilitated by college students’ love of good Mexican food, has had a profound impact on Miguel.

“I feel very grateful for God and the students because my business has found success because of them,” he says. “Because of the students who come here to support me and my business. The students mean a lot to me.”

“I’ve seen a lot of stuff,” Furlong shares in their closing statement, “where we don’t treat Northfield with the respect it deserves. Let’s freakin’ do better I guess.”

To further engage with Carleton student films, check out the CAMS events calendar or find newly released work on the CAMS vimeo account!