Hard Truths and Healing: Elder-in-Residence Program Piloted at Carleton

Dr. Denise Lajimodiere’s week-long residency on campus increased visibility for Native students and prompted thoughts of healing and honest storytelling for attendees

CONTENT WARNING: This piece contains discussion of historical trauma and abuse, as well as that abuse’s effects on current generations of Indigenous people. Please take care of yourself and your mental health. Think about talking to someone if you need to, and consider this list of resources and advice from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

Almost every chair in Weitz 236 is full of students, faculty, staff and Northfield community members as Dr. Denise Lajimodiere walks up to the podium, the title “Bitter Tears: Intergenerational Trauma and American Indian Boarding Schools” projected above her. She speaks in her language and English to welcome the crowd, and dives right into her personal connection to this topic. Her parents and grandparents all spent time in these boarding schools—Lajimodiere calls them “hellholes… somewhere between dungeons and death camps”—and the audience can feel the pain in her voice as she speaks about the rampant abuse and oppression Native people faced in the institutions.

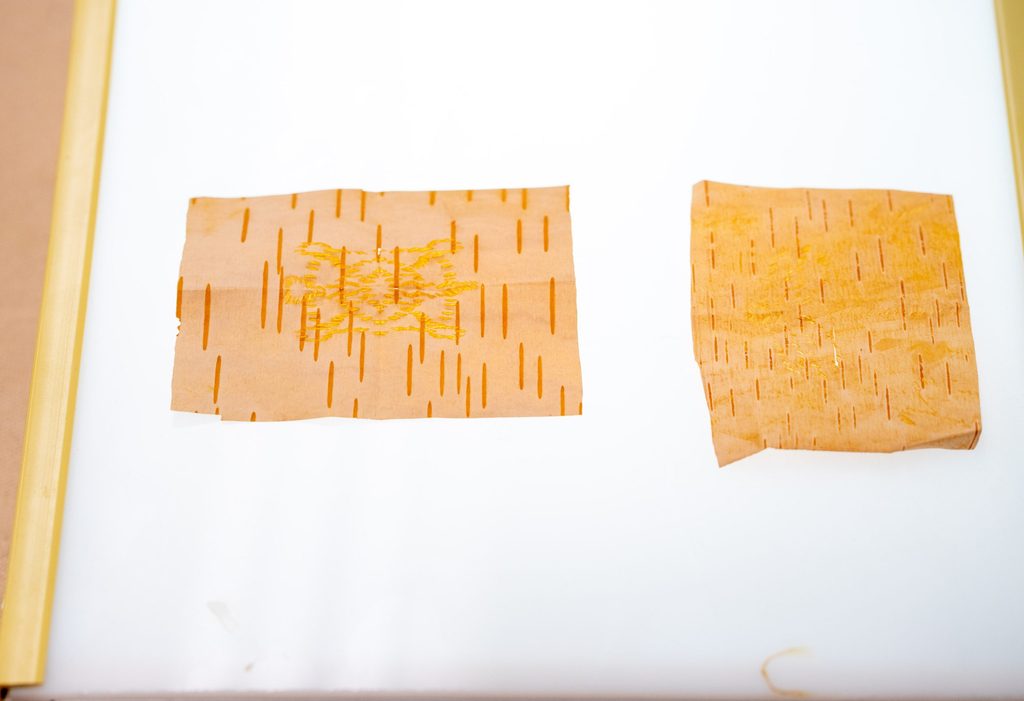

A citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Lajimodiere is a retired professor from North Dakota State University, a published poet and author, a birch bark-biter, a dancer, an artist, and has been an educator and scholar for over 40 years. During this event—part of her week-long stay on campus for a pilot of Carleton’s Elder-in-Residence program—Lajimodiere runs through historical details and photographs from her book, “Stringing Rosaries: The History, the Unforgivable, and the Healing of Northern Plains American Indian Boarding School Survivors,” stating horrific facts and events very plainly. She is calm and poised even as she reflects on an interview she conducted with a man who had been molested by a priest as a child at his school. “I could tell you more sexual abuse stories,” she sighs, “but then I wouldn’t sleep for a week.”

As she talks about the punishments children would face after speaking any language other than English at the schools, the subject of her father comes up. His mouth was washed with lye soap, and the hair at the base of his skull was pulled so he would face up and forward when he was forced to pray in English. Lajimodiere explains that even up until his death last year, her father could not speak his language in public, because he could feel the priests pulling at his hair every time he tried. She calls this trauma a “soul wound,” something that was baked into her father’s very bones.

Lajimodiere comes back to her father often in her discussion—he is a source of both pain and healing for her. She speaks wistfully about him at times, and what his life could have been under different circumstances. “He was so smart,” she emphasizes. What if he was allowed to use that intelligence? What could he have accomplished? Lajimodiere also reiterates that this unfulfilled potential isn’t unique to her father. His story could be the story of any Native man stolen from his parents in those years and brought to such an abusive place.

Even as she outlines appalling stories, though, she makes sure to impart some healing truths as well. “Language is medicine,” she says, “and culture is treatment.” Being able to relearn the language and cultural practices of her nation, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, has helped to heal her spirituality—along with professional therapy, which she recommends for everyone in the room. Whenever it gets especially hard for her, which it often does when handling such personal and graphic accounts of trauma, she thinks of the people she does this work for.

“It’s been hard on us [doing this kind of research],” Lajimodiere admits. “But… whatever I go through, I just think of these people that said [in interviews for her book], ‘Please tell the world what happened to us.’ That’s why I’m here.”

This theme of truth-telling continues into Lajimodiere’s poetry reading as well. While her academic writing exists to tell the stories of other Native people and publicize the research she’s done on boarding schools, her poetry is a different kind of catharsis.

“The poems are all about my family,” she says. “These stories are not in [‘Stringing Rosaries’]… These poems… they’re my sanity, they’re my therapy… I close the [poetry] book and [the traumatic stories] are in there! They’re off of me, it’s my healing.”

Lajimodiere’s poetry also reveals how much of an artist she is at heart, in addition to being a scholar. Her voice wraps around the words lovingly as she reads her work. “Slow Time,” a poem about her grandmother, feels like a warm hug. “Dragonfly Dance,” the title poem of one of her chapbooks, recounts her connection with dragonflies, whose spiritual significance is important to her. It feels like a revelation. “I couldn’t breathe for the beauty” is her refrain in a poem about joining a ceremonial dance for the first time, and her voice is breathless as she says it. Her soul shines through her writing, and the round of applause when she finishes is long and deafening.

After the last question is answered, Lajimodiere makes to leave the podium, but Meredith McCoy, assistant professor of American studies and history, gestures for her to stay. She and religious studies professor Michael McNally reach under their table, producing a beautiful blanket from Sičáŋǧu Lakota artist Dyani White Hawk as a gift for the Elder. “I can’t take any more gifts!” Lajimodiere exclaims, almost tearfully, as they drape it over her shoulders, and the audience responds with a chorus of aw’s. On such a cold day in Minnesota, the celebration warms the whole room, and it’s a lovely final moment to conclude an important program.

ABOUT THE ELDER-IN-RESIDENCE PROGRAM

Organized by McCoy and McNally, Carleton’s 2022 Elder-in-Residence program is one of multiple programs sponsored by the college’s Public Works grant. During her time on campus, Lajimodiere hosted workshops; visited classes; gave two public talks; met with college leadership; shared meals with students, faculty and staff; and offered individual mentoring.

The pilot program is connected to a larger momentum on campus for more robust support concerning Native students, faculty and staff. Together with events like the 2021 celebration of Indigenous Peoples Day, which included the first-ever president-to-president meeting between Carleton President Alison Byerly and President of the Prairie Island Indian Community Shelley Buck, and the recent rechartering of the Indigenous Peoples Alliance student organization, the increased visibility of Native people on campus that Lajimodiere’s visit brings makes McCoy optimistic about the possibility of continuing the pilot program past this year.

“Part of my research is about histories of Native student experiences in education,” McCoy said, “so for me it’s a natural extension of my research that I think about the experiences of Native students here on campus, and also about how we as a campus can do a better job of educating non-Native people about Native histories.”

“This past year has been such an incredible year for increasing the visibility of Native people,” she said. “There’s such an opportunity [with the Elder-in-Residence program and others like it]… to create space to stop and think, what does it mean to us at Carleton to live and work and learn on a campus that was established three years after the forced expulsion of Dakota people from this place… If we’re thinking about ourselves as leaders in the world and creating the next generation of leaders in the world, what kinds of knowledge and skills and values do we want to help folks cultivate?”

That next generation of leaders is the real focus of the program, McCoy believes.

“Ultimately, this is for the students,” she said. “Elder-in-residence programs, no matter what form they take or what campus they’re on, are always about promoting the social and cultural and academic well-being of students, as well as supporting any campus moves towards institutional change.”

MAKING AN IMPACT ON STUDENTS

For Lajimodiere, she hopes that the students who attended Elder-in-Residence program events will carry the information with them and pass it on.

“It’s all about telling the world what happened to us, and it’s probably information that, as young people, they’ve never heard,” she said. “It’s not written in the history books; I call it America’s best-kept secret. So for me, for these students, [the goal is] to listen with open hearts and minds to the information that I’m presenting to them, and to pass on what they’ve learned. To share with their family, with other students and with their community… And do more research on what happened here in Minnesota with boarding schools.”

Julian White-Davis ’23, who took the photos attached to this story of the birch bark-biting workshop held by Lajimodiere, especially enjoyed the residency as a connection to his previous experience with McCoy.

“After taking a couple classes with Meredith,” he said, “this feels like very important work that I don’t think has been done before at Carleton, so seeing so many people come together to learn about these things and put energy into it feels really good.”

He also emphasized how important Lajimodiere’s visit is as a part of honoring Carleton’s Land Acknowledgement, which was established in November 2020.

“It feels like a really good step along the path that we’ve set ourselves on with the college’s land acknowledgement… attempting to tell hard stories,” he said, “especially with [Lajimodiere’s] talk on boarding schools.”

Saheli Patel ’25, who is Turtle Mountain Ojibwe, is happy to have Lajimodiere on campus for multiple reasons.

“She’s kind of my aunt,” Patel said. “I call her my ‘auntie,’ so it’s really nice to have her on campus.”

The first-year student also values Lajimodiere’s unique position at Carleton during her visit here.

“This means a lot, because we don’t have very many Native faculty, and it’s important to have Native voices who can talk to President Byerly [and other administrators]… to just express concerns or pass on values, educate on stories,” she said. “It’s also brought the Indigenous Peoples Alliance, which is our group, together more because we’ve had these events, and it’s been nice to talk to an Elder, because a lot of people were talking about being a little homesick.”

Zia NoiseCat ’23, a member of the Secwepemc and St’at’imc nations, Canim Lake Band in British Columbia, has felt that homesickness soothed a bit by Lajimodiere’s presence.

“It’s been amazing to meet with Professor D one-on-one,” she said, “because it’s been super hard to consider the history of boarding schools… My tribe’s from Canada, and being on campus and far away from family, it’s been really difficult to consider the news with all the uncovering of the mass graves [in Canada], and think about, how do I take time with myself and heal and process? It’s been super amazing to actually have this conversation brought to the forefront of this campus.”

NoiseCat thinks a lot about the storytelling aspect of Lajimodiere’s residency, and her perspective on healing while still being transparent about the truths of boarding schools.

“In the United States, we tend to think that boarding schools and residential schools happened so far back in our histories when really these are generations that are still alive,” she said. “This kind of trauma still affects people, so I think it’s super important to think about, how are we healing and how are we telling these stories? How are we considering how this intergenerational trauma still exists today, and how do we tell these stories in a good way, in a way that is healing for our communities? … We need to tell the truth while also taking care of ourselves.”

The Elder-in-Residence program is sponsored by Public Works, the Distinguished Women Visitors Fund, and the Sustainability Office, with administrative support from American Studies and the Center for Community and Civic Engagement.

Erica Helgerud ’20 is the news and social media manager for Carleton College.