Comps Insider: The Princess and the Pea Clam

To the uninitiated observer, the waters of Spring Creek (which runs across Northfield and detours through the Arb) would likely appear pristine, if a bit murky. Senior geology major Declan Ramirez ’22, however, would beg to differ.

To the uninitiated observer, the waters of Spring Creek (which runs across Northfield and detours through the Arb) would likely appear pristine, if a bit murky. Senior geology major Declan Ramirez ’22, however, would beg to differ.

The creek is, in fact, full of three different types of small mollusks known as Sphaeriid clams: Sphaerium, Musculium, and Pisidium, which is also called a “pea clam” due to its tiny size. Ramirez’s comps concerns the distribution of these clams. He had not initially planned on studying the clams until his advisor posed the idea to him, but he got on board with the sole condition that he get to name the project “The Princess and the Pea Clam.”

“He chuckled,” Ramirez recalled, but didn’t challenge the issue.

Thus began the tale of The Princess and the Pea Clam. What Ramirez did not know was that his journey would end with a plot twist whose implications could impact many comps to come.

Despite their uncommon names, Sphaeriid clams are practically ubiquitous across the continent.

“They can live in almost any environment,” Ramirez said. “You just wouldn’t know unless you look for them because they’re just so small, and to the untrained eye can camouflage as stream sediments.”

The initial goal of Ramirez’s comps was to quantify which type of clams were present in which parts of the creek. He set out to “cut up Spring Creek into different habitats… analyze the quantities of clams in each habitat, and see if they have a preference.”

Ramirez conducted fieldwork along the entire length of Spring Creek, waking up early every morning to make it outside before the heat beat him to the punch. “I… [got] up at 8:00 AM every morning… I worked from then to 12:00 PM in the Geology Department under Jonathon Cooper, which allowed me to make enough money to stay on campus to do the research and buy food. I then usually took a break for lunch and would start field work at 1:00 PM, then work till 6:00 or 7:00 PM depending on when it started to get dark,” he explained.

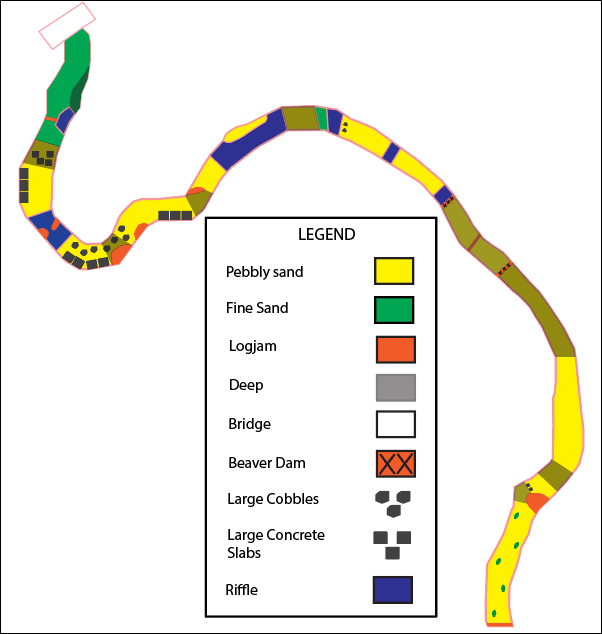

Ramirez described the trajectory of his fieldwork as follows: “First, I walked through the entire river and qualitatively determined which habitats were present.”

He would then document these habitats in an exhaustive digital map that served as his guide to the river during sampling. After completing the map, Ramirez returned to each habitat, where he performed several tests on the stream before taking a sediment sample in a random area. He recalls having to “put [each] sample through a system of sieves, because these clams are so small… the smallest they can get is 0.42mm,” then classified the clams based on species. Finally, he tested whether there was a statistically significant difference between the abundance of clams present in the lower and upper stretches of the creek, within each habitat, and between the habitats.

The fieldwork had its fair share of rough patches, as one might expect. Without a team, Ramirez had no choice but to conduct his research alone—which became substantially more difficult given that he only had a small window of time before the stream froze over, making data collection impossible. He was also treading on unexplored ground.

“Nobody knew,” not even state authorities, “that these clams were there,” he said. “They thought they were there, but nobody had ever studied them and sampled them. We did not know going in… There’s a lot of different research that could be done on these clams in the future.”

Occasionally, the field itself attempted to thwart Ramirez.

“[The research] was fun,” he said, “but it was really hard to do, especially by myself in that river all day.”

He described a particularly harrowing incident: “I sat down in the river once, because it was hot and the river was cold. Never do that. I stood up, and immediately, everything started biting me. I was covered in these… little bitey creatures, and they were attacking me. It took forever to get them all off… I was always on the riverbank after that.”

Ramirez ultimately succeeded in mapping the entirety of Spring Creek, dividing it into sections based on habitat and sediment type, and assessing the clam populations in each area.

“I’m really proud that I did the fieldwork on my own,” he said. “I’d never done that scale of fieldwork before.”

But “The Princess and the Pea Clam” would not have a fairytale ending. Rather, it would end on a cliffhanger.

While researching a section of upper Spring Creek bounded by flood control dams, Ramirez expected to find a combination of at least two clam generas, in line with observations from the other two reaches. He instead discovered that “[Sphaerium and Musculium] were not there… [Pisidium] was there in very low quantities.” This unexpected population decline was, in all likelihood, unrelated to any infighting amongst the clams.

“The literature indicates that there doesn’t seem to be much competition between [the species,]” Ramirez said. “They’re tiny filter feeders, so they’re not going to be competing against each other for resources or for space.”

He concluded that human intervention may have been the cause, as Spring Creek was rerouted around Bell Field in 1921, which likely caused a local extinction of Sphaeriids in this section of the Creek. However, the fact that only a very low quantity of Pisidium was collected in the area is “very concerning… it’s indicating that there might be some environmental degradation in the area.” As they are environmental indicator species, a near-complete lack of Sphaeriids in a site bordered by fruitful habitats indicates an external factor preventing the clams from surviving in that area.

Solving the mystery behind these population discrepancies was outside the boundaries of Ramirez’s project. Still, given that he has fully mapped out Spring Creek and conducted the statistical tests that initially illuminated the issue, future comps projects will likely center around his work. “The Princess and the Pea Clam,” then, is not a one-off story, but the first in a vital series.

As Ramirez finishes writing his final research paper, he remains thankful to his advisor Clint Cowan and the geology department for supporting his work. Of all the clams he has studied, he relates most to Sphaerium, the largest species, because “I like to stay in place and have stability, and they love to just sit someplace and chill.”