Profiles in Teaching: Rika Anderson ’06 on Evolution in the Deep Sea and in the Classroom

Rika Anderson ‘06 is an assistant professor of biology who specializes in understanding evolution. This term, Anderson is teaching Genomics and Bioinformatics, as well as supervising research students and seniors…

Rika Anderson ‘06 is an assistant professor of biology who specializes in understanding evolution. This term, Anderson is teaching Genomics and Bioinformatics, as well as supervising research students and seniors working on comps. This week, I heard from Anderson about some of her work at Carleton and beyond.

How did you get into your field of study?

I have been interested in science since I was a young kid. I started [as a student] at Carleton with an interest in becoming an astronomer; however, my interests shifted over time and I was drawn into astrobiology (the study of life in the universe). I also realized that I love being outside on the water, which drew me to oceanography. It turns out you can combine those two things in the research I do now! And as a former Carleton student, I always wanted to come back to teach at a place just like Carleton someday—I just never expected that it would be Carleton itself.

What is the focus of your research?

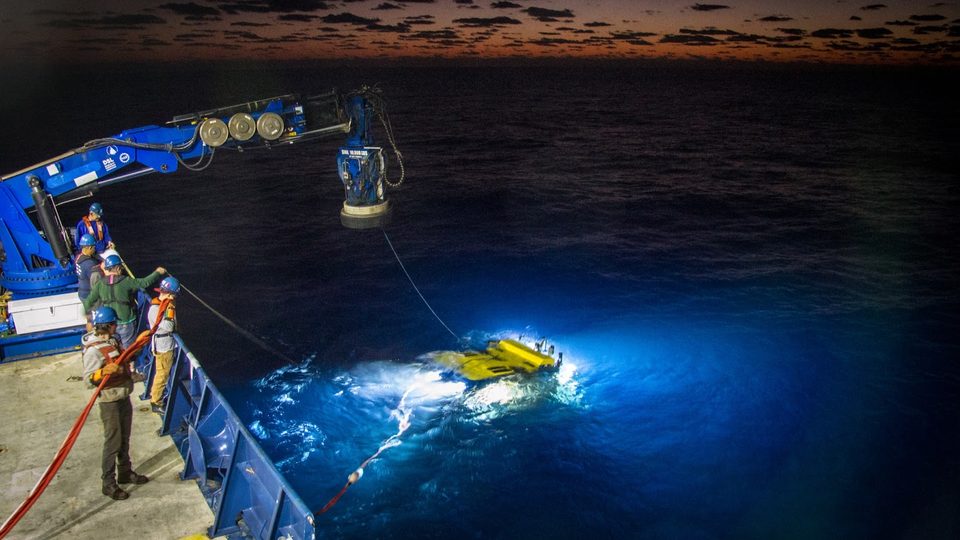

My research lab focuses on two main themes: the first is on marine microbes, mostly with a focus on microbes that live at the bottom of the ocean in deep-sea hydrothermal vents. We go on oceanographic cruises and take submarines (both crewed and robotic) down to hydrothermal vents to collect samples from the hot fluid that comes out of these vents, and we try to understand how the microbes and viruses that live in these habitats adapt to their environment over time. The other wing of my research lab involves work with NASA, and we try to understand the evolution of microbes on Earth through the history of this planet. By understanding how microbes have evolved and adapted on the changing Earth since life began 4 billion years ago, we can better understand how microbes have fundamentally changed our planet and its atmosphere–and that could give us clues about how to detect life beyond Earth.

What are your favorite aspects of teaching?

I love teaching my Genomics class, because I get to watch students learn how to explore giant datasets, and help them work on independent projects they design themselves. We also spend time talking about the intersection between science, society, policy and culture, and it’s always fascinating to hear what my students think about some fairly controversial topics without clear answers. Carleton students are so curious, motivated, intelligent and enthusiastic—and I’m not just saying that because I was a Carleton student myself once.

How do your research and your teaching influence one another?

My research is very much grounded in bioinformatics, and the field of bioinformatics is constantly changing. By staying on top of the field via my research, I can keep my students up-to-date on the latest developments in the field. I also teach a class on the Origin and Evolution of Life, which is closely tied to my research interests in astrobiology. Just last year my students and I read a paper about Snowball Earth—a time when the entire Earth was covered in ice—and I ended up collaborating with the author of that paper on a research project, which was a pretty exciting example of how my teaching influenced my research!