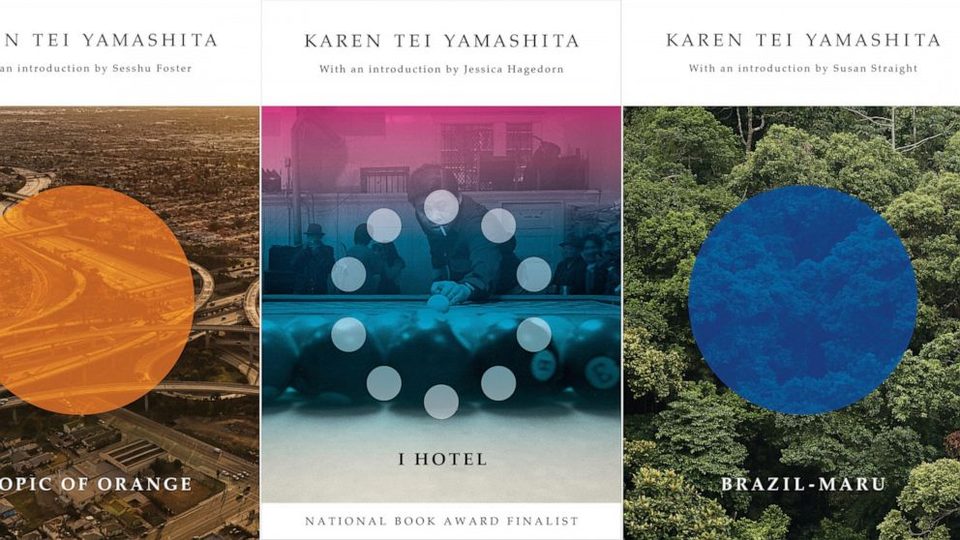

Q & A with National Book Award Winner Karen Tei Yamashita ’73

Karen Tei Yamashita ’73 was named the 2021 recipient of the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. Hear Yamashita discuss the award, her career, and her time at Carleton.

Karen Tei Yamashita ’73 was named the 2021 recipient of the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. Engaging, funny, and warm, Yamashita talked with me last week from her sunny home office in Santa Cruz about the award, her career, and her time at Carleton.

Q: What did it feel like to receive the National Book Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award?

A: I got a call from Ruth Dickie, the director of the Foundation, and it was rather amazing. I’m probably not the usual person to be getting the award; it’s typically someone more well-known and more mainstream, and I never expected to be honored this way. I really just don’t know what to say.

There’s another author, Jessica Hagedorn, who always says, “why are they doing this to us? We’re not dying.” And that’s how I think: I’m still writing, why are you giving this to me now?

I think it’s also a special moment because, for Asian American writers, it has been a long time. Finally, we see a lot of Asian American writers being published and being celebrated. There’s another generation of writers coming up who are amazing, and it’s about time our community got recognized. I’m happy to be here. It’s been a hard two years [for the Asian American community], and I think this needs to happen to say ‘don’t shove us to the side, don’t stereotype us.’ Anti-Asian hate is a reality right now, and it’s not pleasant, but we’re gonna party despite it.

Q: Speaking of Asian American representation, how has your experience as an Asian American influenced your writing and your career?

A: Back in the day, if you were an Asian-American woman in writing, we used to joke that you had to write about a mother and a daughter. Either that or autobiography and memoir. That was the kind of work that people were interested in, and people wanted to tell the stories about their families that they didn’t see represented in other places. But I didn’t really fit that space. And I also couldn’t write about my family, because my mother wouldn’t have been happy about that; and I also didn’t think there was anything particularly interesting about my family or my life. So I had to find other subjects. [As Asian American writers] we didn’t know if we had a future. I don’t know anyone who lives only off of their writing, because that’s not something that happens to us; most of us also have to teach.

It has taken a while for there to be more freedom. It’s a question for writers of ethnicity of how to find their creative space. As a teacher, I often see students of color come to me with white characters, not writing about their families or communities because they assume that no one will be interested. We’re confined in our creative efforts by our situations and by the larger society. There’s a lack of freedom to try different things, and people feel pressured to write about things they might not be comfortable with.

Many of my early books weren’t about Asian American characters, but they’ve been taken into Asian American literature because I’m Asian American. In my first published book, I had only one Asian character, a Japanese immigrant, and the rest were Brazilian. It was all a mixture of fantastic and speculative work, and there were Asian characters, but I wasn’t pursuing the kind of writing [that people seemed to want from Asian American writers].

Q: You’ve lived all over the world, and your stories seem to have a strong sense of place. How do you feel like the places you’ve lived have shaped your writing?

A: Moving to Brazil changed my life. I got the opportunity to go there through Carleton, and the money [from the grant] lasted me quite a while. I lived there for nine years, and I got married and had two children there. In my junior year at Carleton, I went abroad to Japan, where I later returned to study Japanese farming. When I went to Brazil, the two converged and I studied the transplanted Japanese farming community in Brazil; I spent a lot of time studying the details of their lives and culture because I thought I was doing an anthropological project. Place and language have both been very important to my writing and my life, as well as looking at migration and transnational movement.

Q: Tell me more about your time at Carleton.

A: My years at Carleton were important, although of course, I didn’t know it at the time. In my generation and my community, most of my friends and family stayed in California for college. But my family thought that I should leave California, go to a small school, and get a different experience. My family had ties to Carleton, because the president at the time, John Nason, was an old friend of my aunt. He had been part of a group of Quakers who helped relocate college-age students who were put in internment camps during World War Two and sent them to college, and my aunt had worked for him during that time. That connection introduced me to Carleton, which was part of my reason for applying. But I never visited Carleton before deciding to go there. All I had were the pictures in the catalog, and no one told me what Minnesota would be like. No one told me about the snow. My mother, who had lived in Minnesota, just told me that I needed to learn how to fall so that I wouldn’t hurt myself walking in the winter.

I started at Carleton in 1969, which was the year that everything changed. Kent State. A Man on the Moon. The Vietnam War. Protests. When I first got to Carleton, I lived in a Watson double, and the dorms were separated by gender. Watson was all women, we had a curfew, and men weren’t allowed in after a certain time. But after a couple of months, students started independently switching rooms; people would put their names on a sign-up sheet and other people would find a spot they wanted and swap. My roommate and I ended up trading with two boys who lived off-campus, and all of a sudden the dorms became co-ed. There were boycotts, and students stopped going to classes. But because it was Carleton, students couldn’t stop studying. So everyone would be sitting outside, smoking and holding study groups and doing activism.

The other thing about Carleton in those years is that there were only 12 other Asians in my class at Carleton. We all became friends, but it was very awkward. Were we supposed to recognize each other? Would it be weird or really obvious if we all talked to each other? I didn’t want to assume that anyone would be my best friend just because they were Asian. But there just weren’t enough of us.

My roommate was a military kid who had lived on a base in Japan, and so she knew some Japanese culture and some of the language. There was some effort there [from Carleton] to be culturally sensitive because they thought maybe we’d have some similarities. But of course, I’d never been to Japan. So our big bonding activity was that we’d eat ramen together because no one had ramen at the time.

[Carleton] was far away, and I met some beautiful people and great friends, but it was a little strange. Carleton kids are a type. I would say we’re a very earnest, dedicated group of people who want to make a difference.

Q: You publish out of a small Minneapolis press, Coffeehouse Press, which is a bit unusual. Why do you publish with them?

A: It was really interesting to return to Minnesota. That’s entirely serendipitous, and it’s probably because Minnesota is very generous with giving grants to the arts; there are actually several independent printing presses that have come out of Minnesota. Although Minnesota is in the Midwest, it’s been the center of a lot of controversies, and it’s had a very interesting political life. There have been a lot of activist political figures, including a state representative and former Carleton professor, Paul Wellstone. A lot of that history is maybe the reason why Coffeehouse Press is located in Minnesota. The founder, Allan Kornblum, brought me in [as part of an early group of Asian-American writers at the press]. Allan was the first person to accept my manuscript, which I sent in cold, and he called me and told me, “I’d really like to publish this.” I had no idea who he was, and I wasn’t sure if it was even a real call because I was very sick, and I thought maybe I made it up.