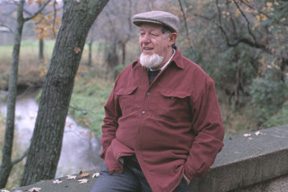

Interview with Keith Harrison, Writer-in-Residence Emeritus

Keith Harrison, professor emeritus of English, talks about his new collection of poetry, “CHANGES: New and Collected Poems (1962-2002).”

Keith Harrison, professor emeritus of English and writer-in-residence at Carleton College for nearly three decades, will launch “CHANGES: New and Collected Poems (1962-2002),” his newest volume of poetry, at 4 p.m. on Wednesday, Jan. 29 in the Athenaeum of Carleton’s Gould library. This collection represents 40 years of writing from a long and varied career in England, Australia and America, much of it from the author’s time as writer-in-residence at Carleton.

Harrison has published and given readings of his work throughout the English-speaking world. His poems and radio plays have been broadcast on National Public Radio, the BBC and Australian National Radio. His poem “Field Notes for the War Against England” has been called the “most important poem published by an Australian in the last decade.” Harrison’s 12 books of poetry and translation include “Points in a Journey,” “Words Against War,” “A Burning of Applewood,” “The Complete Basho Poems (2002)” and a verse translation of “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.”

Harrison, who now divides his time between his old farmhouse in Northfield and various venues in Australia, granted Kelen Tuttle ’04 with an interview this winter. Currently in Australia, Harrison is hard at work on several new books, including a text on academic writing titled “How to Stop Your Papers from Killing You (and Me)” and a prismatic memoir (working title: “Not Quite Ithaka”).

Give us a hint as to what we can expect from your newest volume, “CHANGES: New and Collected Poems (1962-2002).” Is there a theme?

I’m not sure there’s anything one could call an overall theme in CHANGES. As it’s a collection of most of my work in shorter volumes of poetry over forty years, and as one goes through many preoccupations in that time, it’s a very varied book in form and content. Many writers compiling a collection of poems tend to gather their previous books in chronological order. For various reasons I didn’t want to do that. It seemed to me better, as a general organizing principle, to put all the poems of similar kinds (or if you want to use that unpronounceable word, similar ‘genres’) together. Over the years I’ve written a lot of dramatic monologues and portraits, so they are now all in the same section. The same with the songs, translations, and so on. There are 15 sections in the book and, despite what I just said, there is a kind of chronology, and it forms, so to speak, an arch: I’ve begun and ended the book with two very different groups of newer poems. The opening section, called BROWN MUSIC, as the title implies, has a rather autumnal tone, whereas the last section, called SNAIL-TRACKS, is written in very small syllabic stanzas of eleven syllables, is somewhat wry and, on the surface, lighter. Between those two groups I dive back in various ways to all the earlier work I want to keep.

I was interested, in making this collection, to give a new shape to my work so far, not a simple linear arrangement. The notion of change (it is not really a theme, but a principle if you like) is both explicit and implicit in the book. There are (I hope) funny poems, satires, dark meditations, children’s poems, long narratives, tiny poems, stories, sonnets, haiku, and more. As my old friend, A.K. Ramanujan (to whom this book is dedicated, in memoriam) once said: We all go through an amazing variety of moods and modes of being in a year or a decade and even in a single day, and I wanted to catch something of the variety, the unpredictable modulations that are the very stuff of being alive.

I’ve always been interested in writing different kinds of poetry, from so called experimental sound poetry to elegies, from stories for kids to dense and allusive love poems. I see each poem that comes to me as, among other things, a technical challenge, an exploration. That gives another dimension to the title of the book.

Much of your work contains distinctly Minnesotan sights and sensations. Can we look forward to more thoughts on Minnesota in the new volume?

Two landscapes are welded to my bones. One I was born into — that of southeastern Australia. The other is the undulating farm country of southern Minnesota, which grew on me very gradually. In fact, it wasn’t until I went out into the fields and, for some years, tried to sketch the landscape around Northfield and Dennison and Webster that I began to respond to its subtleties of rhythm and tone, its flora and creeks, its smooth low hills that sometimes look like the backs of sleeping whales. I’m particularly taken with the Minnesota fall — all those long ribs in the plowed fields and the astonishing variety of muted browns, greens and russets. So yes, the Minnesota landscape is still there in the recent poems. And the Australian landscape too.

Poems, for me, are born in particular places and I have always felt that its important to take the reader there as much as you can. Abstractions, as a rule, don’t do that; you need clear images, a sense of the texture and feel of a place, an immediacy. I have always tried to get that. There’s a series of fifteen black and white prints by Karin Calley in the book — one for each section. They are not direct illustrations of anything in the poems. But they are based on plants of the southern Australian tablelands and in that sense they are also very specific.

The radio play called The Water Man is set very firmly among the fields and the imagined people right where I have lived for thirty years in Hackberry Hollow, on the edge of the College arboretum. The locus of the action is an old farmhouse (whose barn is still standing) about a mile south from me on Spring Creek Road. And the ghost in the poem is someone I know quite well.

In some of the poems in the last section I have tried (it wasn’t a conscious aim) to capture the sense of ageless stillness, the ‘deep dry time’ of the Australian bush in summer. I think we all carry our own private landscapes with us, as well as our ancestral voices. They spring out at will. They want to be experienced again, celebrated, heard.

As a professor and writer-in-residence at Carleton for nearly three decades, tell us what (or who) on campus has inspired you in your work. Have you seen your writing develop in a new way as a result of your time here?

One thing the students have helped me with immensely is in the combining of poetry with music or, to put it more accurately, sound. In my last few years at Carleton we had classes on poetry in performance in which we tried to embed poems in an ambiance of overtone chanting and other sounds. I think this practice goes back to the real roots of poetry, as in Homer and early ritual and religious ceremonies. Poetry is meant first of all to be heard; plays are meant to be experienced in performance. We can easily forget that in the academy, where everything can too easily become a silent text or a script. I really believe that poetry as performance is right now at the edge of a renaissance. We see its relatively crude foreshadowing in rap poetry, and a host of other experiments. For years I have thought that an electronic Paradise Lost would make marvelous radio. You know, an attempt to find the really rare and direct synthesizer music of Heaven and Hell. Great spaces. And the richness of Milton’s words in those spaces, with its meanings all intact and audible. I think it would appeal to the same audience that listens appreciatively to jazz and pop and the news. But it has to be done well. It has to seize the ear with an immediate sense of beauty and wonder.

The possibilities of poetry as public entertainment and more, much more, are almost limitless. One of the great things about Mozart was that, in The Magic Flute, he took the most common vehicle of public entertainment in his time – the popular, magic, musical theatre, with its weird beasts and rough humor — a kind of vaudeville, that the Beatles would have loved — and, within that form, he gave us some of the most beautiful and most meaningful music/drama of all time. You can have great poetry, and bread and circuses at the same time, if you find the right vehicle. It’s all there waiting. People are thoroughly fed up with the second-rate stuff by which we are surrounded and stupefied for too many hours of the day.

On a different note, how does it feel to be releasing a collection of 40 years of work? Does the new volume feel complete?

Writers like to make a distinction between their latest book and their last book. This is my latest book, not, I hope, my last. And, in a sense, the collection won’t be complete until I die. I just wanted to get a start on the process before that happens! Meanwhile I’m brimming with ideas, for poems, and much else. There are three more almost-finished books on the skids, one a kind of prismatic autobiography — an odd ascription I know. But I want to do something which is not linear, but a pattern of presences, some of them recurring, in much the same way as we remember people and events, with an immediacy so that everything feels as if it is happening in present time.

The book is called “Not Quite Ithaka,” for reasons which become clear as it proceeds. Unlike Odysseus, we are never really home; we are always arriving. On the way we meet all kinds of people who get us closer to ourselves, to our deep roots and our individual meaning. That’s what the book is about. It also contains poems AND the contexts in which they occurred. So it’s not a memoir in the usual sense. I find linear memoirs (‘I was born in Eastern Iowa, and my family’ etc…) unsatisfying. We don’t live our lives on a line, but in pools and back-eddies and valleys and cascades and stillnesses, where things are always changing, and time plays all kinds of tricks: the anger that you felt one morning ten years ago is much more vivid that the muffin you ate for breakfast this morning. Can you even remember what you had for breakfast this morning? I can’t. Time, for all of us, has a subjective rhythm which has little to do with the time of clocks. It’s that sense of time that I’m after as I tell ‘my story’ in “Not Quite Ithaka.”

The other two books are about writing. I want to help students with the craft of essay writing and the crafts of poetry. I’m spurred on by the thought that I might have something useful to offer, and I hope I’m not deluded. I have found that most books on writing are not very interesting to read. I don’t want to write one, or two, of those. If mine aren’t at least readable and, with luck, helpful, I will have failed. There, now I have really put myself on the line!

Do you have a favorite or most memorable poem we can leave the reader with?

Your question can mean two things, so I’ll give you two answers. If you mean a poem of my own I’d like to share with your readers, I will give you this one. It’s set on a farm on Wisconsin and it’s a sonnet, though I don’t know of any other sonnet in the language quite on this subject. It’s called “Here,” and it goes like this:

The day was still as honey in a bowl,

The maple-sap came fast, with winter gone

The cattle stood beside the bright snow-pool,

Their dung packed down and steaming in the barn.

No help for it, go get your fork and spade

For even those who serve the world with wit

Are trundling down into the deep barn-shade

And blocking up their nose, and shoveling it.

You hacked and grunted all day at my side,

And then we heaped it, drove it up and flung

Great cartloads on the cornfields, near and wide,

Breathing new air rich with earth and dung.

Then stood a little while, single and whole,

And the day still as honey in a bowl.

Alternatively, your question could mean: do I have a favorite poem of mine by someone else that I’d like to share with you and your readers? I have many candidates so it’s a question of choosing one among hundreds. So I’ll give you a translation of a poem of Rilke by James McAuley, a fine Australian poet who produced this at the age of 21. It’s called, simply, “Autumn,” and here it is.

Heart, it is time. The fruitful summer yields.

The shadows fall across the figured dial,

The winds are loosed upon the harvest fields.

See that these last fruit swell upon the vine.

Grant them as yet another day or two

Then press them to fulfilment and pursue

The last sweetness in the heavy wine.

You shall be homeless, shall not build this year.

You shall be solitary and long alone.

Shall wake, and read, and write long letters home,

And on deserted pavements, here and there,

Shall wander restless as the leaves are blown.

I have carried that poem with me since I was a boy. I hope it sings in your mind and your readers’ minds, as it has done in me for all that time.