Dr. Mays Imad, a neuroscience professor at Pima Community College as well as their Teaching and Learning Center coordinator, recorded a webinar on trauma informed teaching and learning in April 2020. As the education landscape shifted in response to the pandemic, she shared how her background in neuroscience can inform teaching practices to be more effective in the midst of nation-wide trauma. Her webinar asked the question: “How do we teach to the lonely, the fearful, the broken?” This question continues to be relevant as the pandemic drags on a year later and because trauma is widespread in our society for a variety of reasons.

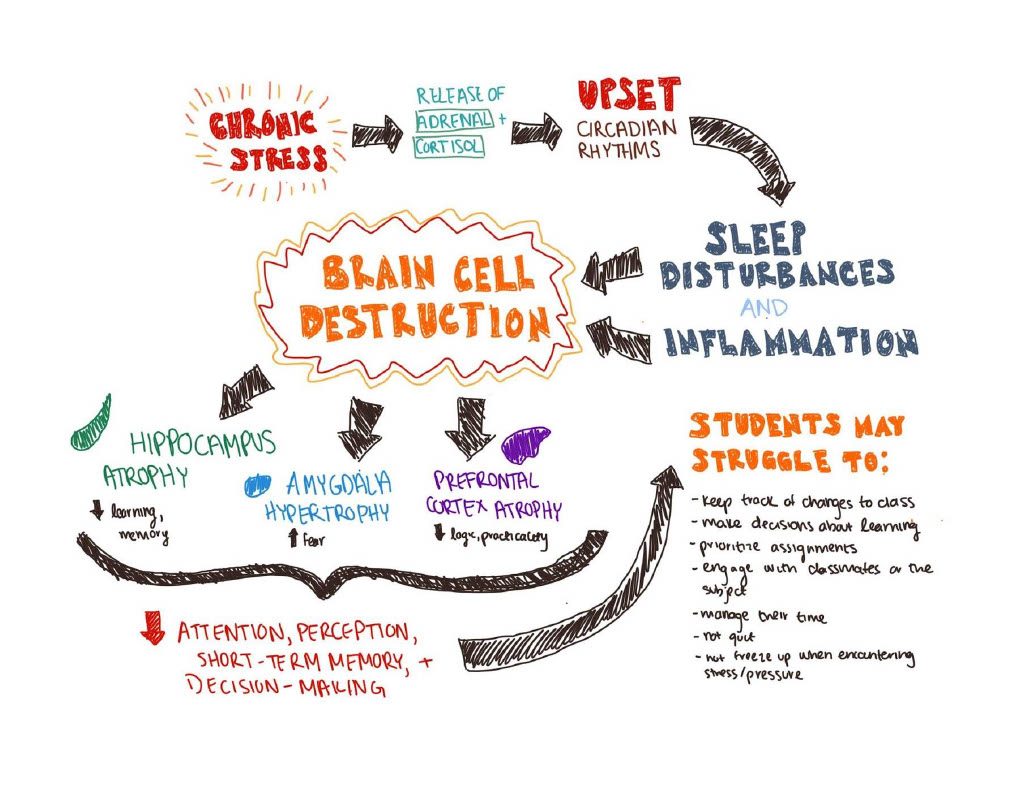

She first explained a few definitions of trauma, but emphasized the significance of neurologist and traumatologist Robert Scaer’s interpretation in the context of COVID-19, which asserts that trauma arises from negative events that put an individual in a position of helplessness. Next, she described the connection between the effect of trauma on the brain and student learning, which I’ve depicted in the diagram below.

After demonstrating the mechanisms through which trauma can negatively impact students’ ability to learn, Dr. Imad encourages us to ask: How can teachers best facilitate student learning during times of trauma? To answer this question, Dr. Imad establishes four key components to trauma informed care and suggests strategies to implement them in the classroom.

- Inform: Establish normalcy of talking about trauma and fight or flight responses in the classroom. Encouraging students to keep journals can help teach their brain to distinguish stress and immediate threats to life. Additionally, reminding them to focus on breathing, walking, or laughing can activate their parasympathetic nervous system, which brings the body back to a state of rest and relaxation.

- Connect: Engage in radical hospitality by being present, communicating often, intentionally, and transparently, and reminding students that they can talk to you. Facilitate community in the classroom and between students, and include assignments that highlight beauty within your discipline or allow students to showcase humor or share their own interests.

- Protect: Make space for “reflective hope” and “grounding empathy” through assigning journals and reflections, and creating flexible structures for students to use.

- Redirect: Build students’ skills and competence by focusing on materials already covered (“remember when…”), asking students to come up with topics they want to learn about, talking about the future, and keeping students engaged.

Lastly, I wanted to highlight a few key insights and facts she included that I found to be especially impactful:

- The power of personal connection: personal relationships with faculty members made students far more likely to be successful later in life (2014 Gallup-Purdue Index)

- Dr. Erick Gbodossou, the director of an NGO which promotes African traditional medicine, said, “When you want to become a healer, you must begin by forgetting about yourself.” Especially during this pandemic, Dr. Imad uses this quote to argue that professors might need to focus on balancing student needs with the ordinary goals of the course.

- At the same time, you can’t teach what you don’t know – you must first prioritize your own well-being and support system before you can support your students.

You can listen to the webinar or read Dr. Imad’s piece in Inside Higher Education.

You can read more about Dr. Robert Scaer’s work on trauma in his book The Trauma Spectrum: Hidden Wounds and Human Resiliency (W.W. Norton & Company, 2005) or his The Body Bears the Burden: Trauma, Dissociation, and Disease (Haworth Medical Press, 2001). Or watch an interview “Understanding Trauma with Dr. Robert Scaer,” conducted by Craig Weiner.

Add a comment