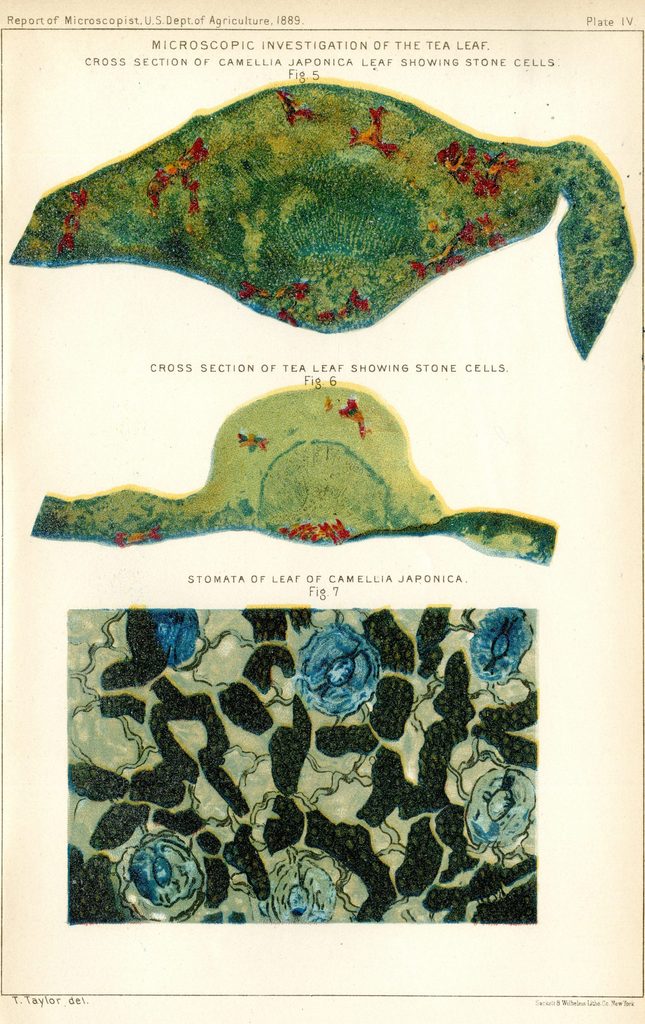

Lower Epidermis of Leaf Showing the Stomata and Chlorophyll Cells [Fig. 1]-

Microscopic Investigation of the Tea Leaf

Illustrated by T. Taylor

Printed by Sackett & Wilhelms Lith Co., New York

First Report of the Secretary of Agriculture- 1889

Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889

Gould Library Government Documents

The books on display here, all from the collections of Gould Library, reveal the beauty and order of hidden worlds. In these volumes, microscopic images are deployed for a variety of reasons: Sometimes their purpose is purely practical (to certify the purity of a sample of tea, or to facilitate the identification of diseased blood). In other cases, as in Felice Frankel’s close-up view of Velcro, their job is as much to inspire curiosity and wonder as it is to illustrate a scientific phenomena.

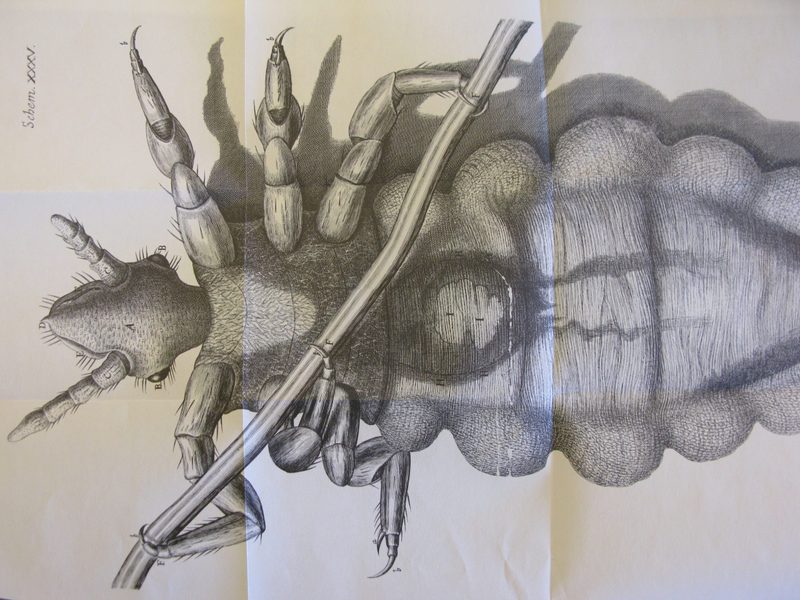

Schem XXXV – Micrographia

Schem. XXXV.

Robert Hooke

Micrographia; or some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made

by magnifying glass, with observations and inquiries thereupon, 1665

Unabridged facsimile of 1665 edition

New York: Dover Publications, 1961

Gould Library Collections

“…modern medicine and all sciences are dependent upon the new worlds that have been discoverable only by this aid to vision… To Robert Hooke alone must be ascribed the honor of having caused the great capability of the microscope to be realized in England.”

Robert Hooke’s Micrographia is one of the earliest, and best-known, examples of the role of images made through a microscope to accompany a scientific text. Hooke and his contemporaries recognized the power of the microscope to reveal a world of perfectly formed details of common insects otherwise invisible to the naked eye.

1. From the preface, p. vi