One of the roles of the Carleton Office of Accessibility Resources is to ensure that all students at Carleton have equal learning opportunities. At one time that work focused primarily on assisting students with a particular disability to be able to access the written and aural material for their classes. Over time, however, this work has shifted away from how individual students receive information, and towards how the information is presented in the first place. This shift towards designing more accessible material and instruction has been somewhat formalized under the banner of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Sam Thayer, the Interim Director of Accessibility Resources, is a great Carleton resource for information about UDL in general, and about how these ideas are being used at Carleton. Academic Technology can help translate UDL ideas into reality through careful use of various instructional technologies.

UDL is the name given to a framework for designing courses, learning material and curriculum that is inclusive and accessible to all students. The notion of Universal Design was originally borrowed from the fields of architecture, interior, landscape and product design, which were and are focused on creating environments and products that are usable by a wide range of diverse individuals. (Follette Story, Mueller, & Mace, 1998). Silver, Bourke, and Strehorn introduced this idea in higher education as a different approach to making instruction accessible, and designing for the broadest audience from the start, rather than retrofitting existing learning material to “level the playing field” for those students in need of accommodations.

McGuire, Scott and Shaw define the nine principles of universal design for instruction:

Equitable use: Instruction is designed to be useful to and accessible by people with diverse abilities. Provide the same means of use for all students — identical whenever possible, equivalent when not.

Flexibility in use: Instruction is designed to accommodate a wide range of individual abilities. Provide choice in methods of use.

Simple and intuitive: Instruction is designed in a straightforward and predictable manner, regardless of the student’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level. Eliminate unnecessary complexity.

Perceptible information: Instruction is designed so that necessary information is communicated effectively to the student, regardless of ambient conditions or the student’s sensory abilities.

Tolerance for error: Instruction anticipates variation in individual student learning pace and prerequisite skills.

Low physical effort: Instruction is designed to minimize nonessential physical effort in order to allow maximum attention to learning. Note: This principle does not apply when physical effort is integral to essential requirements of a course.

Size and space for approach and use: Instruction is designed with consideration for appropriate size and space for approach, reach, manipulations, and use regardless of a student’s body size, posture, mobility, and communication needs.

A community of learners: The instructional environment promotes interaction and communication among students and between students and faculty.

Instructional climate: Instruction is designed to be welcoming and inclusive. High expectations are espoused for all students.

These nine principles draw also from Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) and the idea of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). WCAG helps to ensure that technology is accessible and usable for all students and provides specific techniques for making online material accessible to assistive technology and usable by students with disabilities.

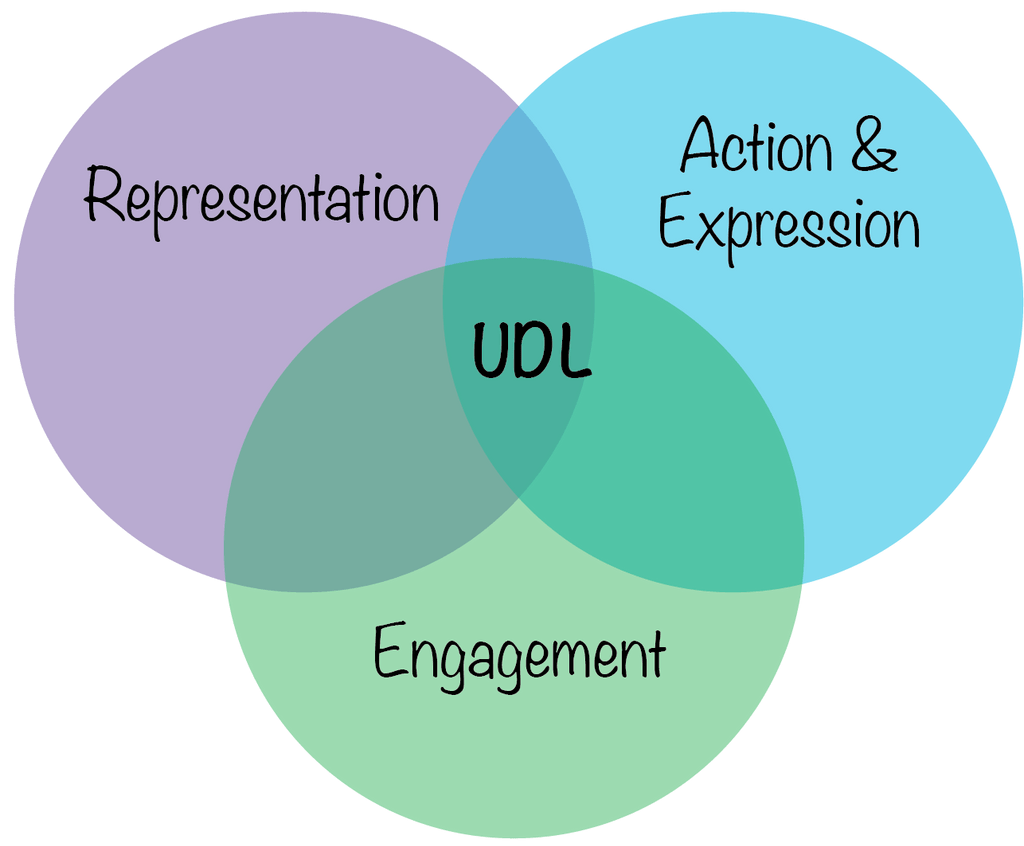

Universal Design for Learning is a related set of guidelines for optimizing teaching and learning, based on providing avenues for multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and towards the goal of helping students to become self-directed and self-regulated. These guidelines are not only supporting students with disabilities but all students in their varied learning environments.

Sam Thayer notes that not every effort towards universal design has to be overly complex. She has collected some practical examples of how our faculty operationalize UDL principles in their courses:

Marty Baylor makes adjustments for her students, without needing to be explicitly asked for them. Some of those adjustments have been:

- Considering an adjustment for the entire class rather than for a single student with a disability accommodation.

- Providing a way for students to contact her with questions during the exam period.

- Allowing self-scheduled exams for flexibility.

- Allowing students to miss a certain number of posts or warm-up questions that are due before every class.

- Giving a 24-hour extension on one weekly assignment.

- Dropping each student’s lowest weekly assignment grade.

Chico Zimmerman’s suggestions include:

- Always using Moodle for every class, and placing the Accessibility Resources statement at the top of the course page.

- Emphasizing the need for two-way communication with students.

- Planning to be flexible in addressing their needs.

- Making all deadlines clear from the start, and avoiding last-minute changes, especially to high-stakes assignments or activities.

- Anticipating the types of challenges your assignments may present, and working to minimize those that might penalize students with disabilities.

- Providing a rubric or evaluative criteria for every high-stakes assignment.

- Avoiding or limiting assignments that are strictly timed as much as possible.

Sam reports that students have shared suggestions with her as well. Some of the things that have stood out to students are:

- Always turn on captioning when you show a video.

- Add an inclusive learning statement to your syllabus, and mention Accessibility Resources on the first day of class.

- Take advantage of Moodle by uploading any class information or presentation slides.

- For students with testing accommodations, make arrangements so that these students are able to ask questions during their exam.

- Check in with students and maintain an open dialogue.

Sam notes that while UDL is a broad topic that encompasses a lot, it’s perfectly normal to start with small changes. UDL is not all-or-nothing, but rather a process of making changes to courses and teaching practices that improve the experience for every student. For more ideas about how to get started, the LTC has published a blog post that outlines some practical suggestions for making your class more accessible, and also provides resources related to Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. Sam reminds us that changes don’t have to be overly complex to me meaningful — small things can have a big impact.