Beginning in the 19th century women were being hired as workers to compute astronomical data. These computers had been employed in small numbers at Harvard for a number of years. However, the big break through for women in this field came in the 1880s when Pickering, the director of Harvard Observatory, decided to take on the project of the Henry Draper Catalog.

“The application of photography to astronomy, whereby the determination of star-positions, spectra-type, variability,etc., become laboratory work rather than observatory work, has wonderfully increased the opportunities for women in pursuit of the truths of nature…But the most extended application of the aid of women in this specialty has been under the directorship of Professor Edward Pickering at Harvard Observatory, where a large force of women is constantly employed under the supervision of Mrs. Fleming.” (Popular Astronomy 6(1898)p.223-224)

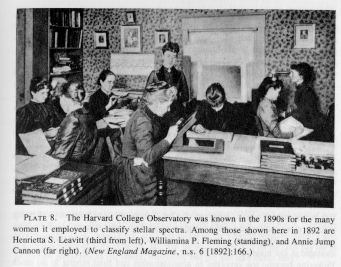

Henry Draper had begun a project to catalog all the stars in the entire sky, but he died long before it was complete. His widow, however, wished the project to be continued in his memory and eventually chose to donate money to Harvard for its completion. These women began the painstaking task of cataloging all the stars that could be photographed and classifying their spectra. The women were paid 25 to 35 cents and hour of work six days a week, seven hours a day. This salary was below what the women entering clerical work at the time were receiving though it was above the salary of the average factory worker. Considering that most of these women had college educations though the salary was rather meager. These women are pictured below at work at Harvard in the 1890s. Henrietta S. Leavitt, Williamina Fleming, and Annie Cannon are among the women pictured.

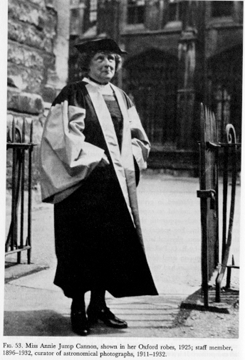

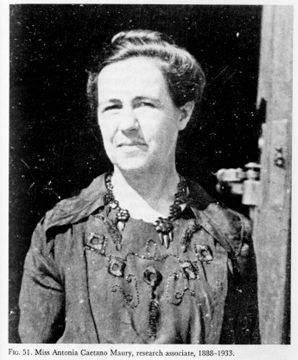

Annie Cannon is probably the most famous of these women. She cataloged thousands of stars and was eventually given the title, Curator of Astronomical Photographs, succeeding Fleming who had also held this title. Cannon developed a system of classification for these stars which was eventually adopted as the standard with some slight alterations at the 1910 meeting of the International Astronomical Union. Antonia Maury also developed a classification system which was a bit more complex. However, her system anticipated the connection between temperature and luminosity which we now see in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. Both of these women did incredible work at Harvard Observatory and deserve to be recognized for their achievements.

Antonia Maury also developed a classification system which was a bit more complex. However, her system anticipated the connection between temperature and luminosity which we now see in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. As Cecilia Payne wrote in her autobiography:

“Essentially her system anticipated the basic concept of the modern classification developed by W.W. Morgan and his associates, which specifies luminosity classes. For, Enjar Hertzsprung was not slow to point out, her third subdivision segregated the stars of high luminosity. But Miss Maury’s classification came too late: the Henry Draper system was already entrenched and her classes, though physically more significant, seemed unnecessarily elaborate.”(Payne-Gaposchkin p.148)

Maury is featured in the picture below.

One of the other women astronomers at Harvard was Williamina Fleming. Fleming became a full time employee at the observatory in 1881 despite a lack of any math, astronomy, or physics background. She had been Pickering’s maid when he decided to hire her as a computer at the observatory. She took charge of the Henry Draper project in 1886 when Nettie A. Farrar decided to leave to get married. She eventually became the first woman to be designated Curator of Astronomical Photographs in 1899. This was the first corporate appointment of a woman at Harvard ever.

There is one very interesting story about why Fleming was hired. Supposedly, Pickering was fed up with his male assistant and informed him his maid could do the job better. He then set Fleming to the task and she proceeded to carry out the task much more efficiently and accurately than the assistant. As a result Pickering hired her on the spot.

Another of the prominent women at Harvard was Henrietta Swan Leavitt. She graduated from Radcliffe in 1892 and came to work at Harvard. As with the other women she made many great contributions to the study of Astronomy.

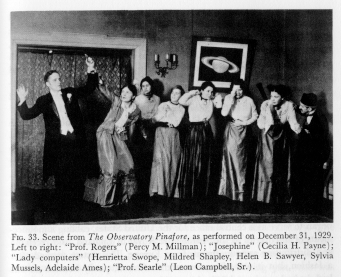

At one point the observatory staff wrote an performed a play called the Observatory Pinafore after the play H.M.S. Pinafore. The play was originally to be preformed under Pickering, however, he retired and the play did not take place. Later ,with the addition of Harlow Shapley and and Cecilia Payne, the play was performed on December 31, 1929. The performance is featured in the picture below. Those included are Cecilia Payne, Henrietta Swope, Mildred Shapley, Helen Sawyer, Sylvia Mussels, and Adelaide Ames.

The women pictured here as well as many more were actively engaged in astronomical work at the turn of the century. The period between 1880-1920 saw the creation of a place for women in astronomy. It is important for people today to recognize these women and the contribution they have made to astronomy.

The information and pictures on this page were drawn from the following sources:

- Payne-Gaposchkin, Cecilia. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin An Autobiography and Other Recollections. Katherine Haramundanis Ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Rossiter, Margaret W. Women Scientists in America: Struggles and Strategies to 1940. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

- Jones, Bessie and Lyle Boyd. The Harvard College Observatory: The First Four Directorships, 1839-1919. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

- Davis, Hermann. “Women Astronomers” Popular Astronomy 6(1898) p223-224.

Return to Michele and Margaretha’s Women in Astronomy Page.