When classics professor Chico Zimmerman arrived at Carleton 27 years ago, nobody had a desktop computer on campus.

How times have changed.

“I couldn’t do what I do without technology,” he says. “Well, I could, but not as efficiently.”

Despite teaching in a discipline often perceived as antiquarian, Zimmerman says the classics have always been progressive in embracing technology. His own class is a perfect example of that, and more broadly, of how Carleton professors across all disciplines are retooling their teaching for new technology.

One of the most common forms of teaching with new tools is taking is in the form of flipped classrooms—the concept, Zimmerman says, is not new, but technology makes it easier and more feasible to leverage class time better. He video records himself explaining a given topic—say, scanning dactylic hexameter in Latin poetry—so students have an inkling of the concept before coming to class. Now, instead of lecturing for 30 minutes and working with students for 20 minutes, his entire class period is devoted to questions, practice, and discussion.

Video capture, he says, also lends itself well to peer reviews, teacher feedback, and instruction in areas outside of class content (like the video he recorded on how to use a dictionary, after noticing several of his students floundered with this old technology).

As effortless as Zimmerman makes teaching with technology appear, support for faculty members is critical. “Putting your content online is not just a simple thing,” says Janet Russell, Carleton’s director of Academic Technology who has also taught biochemistry both residentially and remotely. She and her staff offer pedagogical support for faculty members who want to implement new technologies in their classrooms but might not know where to start.

“To really develop their courses around new tools, faculty need to be paired with Academic Technologists and other support staff, and they need release time,” Russell says.

“A lot of us weren’t trained for this in graduate school,” says political science chair Greg Marfleet. “To stay at the forefront of teaching, we’ve got to constantly train if we want to be relevant—and help our students be relevant.”

Marfleet has seen firsthand the benefits of technology training. About a decade ago he attended a 10-week summer methodology consortium where he “stumbled onto” a class on computational modeling. Here, he learned about an open source program called NetLogo, which analyzes complex systems.

I bet I could teach students how to do this, he thought. So when he returned to campus, he designed an original course called The Complexity of Politics, using the new software.

Open-source software in particular is where Marfleet sees teaching tools headed, along with bring-your-own-device classes. He encourages students to bring their laptops and smart phones to class so any class becomes a lab.

“With open source software and students’ own devices in class, they can install the program, work with the data, take it off campus, and have the flexibility of working anywhere,” he says. This is essential, he adds, because pressure on physical lab space is always high. Booking time is an issue, support is an issue, and the lifecycle of the machines themselves is an issue.

“We have to start thinking about infrastructure to support a bring-your-own-device model,” he says. For example, he has a spare laptop he brings to class in case any of his students don’t have one. The college, he suggests, could look into how it utilizes old laptops collected from faculty and staff members.

Beyond physical needs, like laptops, Russell says that software teachers need is becoming more and more personalized. Adaptive learning tools will push content to an interactive website where a student struggling with one concept is led down one path, and another student stuck on a separate concept is taken down another. Learning analytics tools will also help teachers focus on specific needs; with this type of software, students complete exercises online and are given immediate feedback for wrong answers rather than waiting for instructor comments. Additionally, these tools give teachers a snapshot of all the questions the class answered incorrectly so lecture time can be used to focus on what the class needs.

“We need to ask ourselves, do we want to be a leader with technology-enhanced learning, or play it safe?” Russell says.

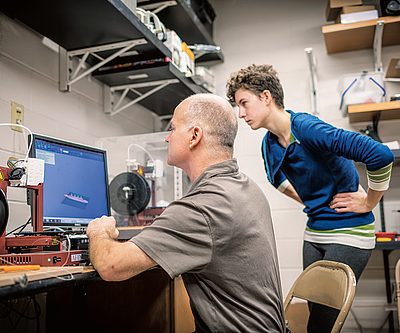

At the same time, leading with technology doesn’t always mean abandoning old pedagogy, cautions art professor Stephen Mohring. His department has a new 3D printer that will make rendering a drawing into an actual object easier, but he says the more important tool he has this term is the time he has to determine how to best integrate the technology into his class thanks to a targeted opportunity grant.

“We teach so intensively at Carleton,” Mohring says. “And when you’re teaching that intensively, you can’t think deeply about doing something different. The only time we have to think about improving our classes is when we’ve been given grants to do that, to be released from a class or two.”

Mohring credits trustee Jack Eugster, who has supported several target opportunity grants, for understanding the needs of teacher development. “He makes a point to have a conversation with the professor who’s going to be affected by the time he’s giving them. And he gets to see the excitement in our eyes when we talk about what we’re going to be doing—and that excitement is like a kid’s just before digging into a bag of Halloween candy.

“I don’t think any of us is happier here than when we get time to really think about teaching,” he says. “After all, that’s why we’re in this game.”

And when it comes down to it, Zimmerman says, teaching today isn’t much different from teaching 27 years ago. “The affective part of learning is never going to be unimportant,” he says. Teachers need what they’ve always needed—to be cognizant of the needs of their students. All the bells and whistles of technology simply help teachers do what they do better.

“As long as an 18-year-old brain is the same, teaching will largely remain the same,” Zimmerman says. “I’m pretty upbeat about technology and the future of teaching.”

Technology on the horizon

What teaching tools does Academic Technology see in Carleton’s future?

- A next-generation Idea Lab for students to work out ideas with mapping, high-end video editing, music composition, and other digital projects

- A telepresence room for online and global learning

- A recording studio for faculty members to record and edit lectures

- A rapid approval process that could quickly green-light experimental initiatives for a limited term