I have to be honest: I’ve had medieval movies on the mind, lately. When your comps topic is Robin Hood, there’s just so many opportunities for doing ~supplementary research~ in the world of cinema. So when I heard that this term’s Intro to Medieval Narrative class was going to be showing the movie The Green Knight on Wednesday, I knew I had to go. Ever since I saw the movie when it came out in theaters, I’ve wondered: what would an actual medievalist think of it?

Luckily, Laird’s resident medieval expert was willing to talk with me before the showing. I found Professor George Shuffelton in his office on Wednesday afternoon, undeterred by the snow. Warning: mild spoilers ahead (for The Green Knight. Also for the Kevin Costner Cinematic Universe (KCCU)).

If you haven’t heard of it, The Green Knight is the David Lowery-directed adaptation of the medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Starring Dev Patel as Gawain, it’s a strange, fantastical take on the old story (it’s produced by A24, if that gives you any idea of the vibe Lowery is going for). There’s trippy mushrooms, there’s an undead maiden, there’s a CGI fox (I almost forgot about the CGI fox!). If you have read the poem, that might confuse you — but don’t worry, you’re not the only one. While George appreciates some of the additions the film makes to the classic tale, he didn’t have any easy answers for me about the film’s drastically different ending, other than that “it really emphasizes the way Gawain fails” (Don’t worry, that’s as spoilery as we’ll get).

Generally, though, The Green Knight is a bit of a departure from your typical medieval film, which seems more focused on spectacle or action than catering to the A24 crowd. Take the Robin Hood movies that I’ve been watching, for example. Russell Crowe’s is a run-of-the-mill medieval war movie — his Robin Hood ends up fighting the French with King John in a rather perplexing version of events. The bizarrely dystopian Taron Egerton Robin Hood (which, to be honest, I haven’t actually seen) is a Marvel-wannabe that flopped at the box office. And of course, there’s Kevin Costner’s Prince of Thieves.

George doesn’t remember much beyond the Bryan Adams song written for that movie, which to be honest is probably for the best. Kevin Costner as a 13th century outlaw…. kind of just looks like Kevin Costner. (Even his hair is the same in every movie he’s in, whether it takes place in the 1860s or the 1960s. Or a dystopian wasteland.) I think he might be going for a British accent at some points, but when it doesn’t work, he just gives up. Would I recommend watching the movie? No. But I would recommend watching the opening credits, if only for the beautiful moment where Kevin Costner’s name is superimposed over the Bayeux Tapestry:

If that doesn’t spark some cognitive dissonance, I don’t know what does.

Still, as an A24 girlie myself, I had to wonder about the possibility for more artsy medieval films, even in the post-Game of Thrones-era of pop fantasy. George assured me that “there’s always been a strand of that art movie that’s interested in the medieval ages, probably for different reasons,” citing examples like Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal along with the work of Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini created some bawdy versions of Chaucer and Boccacio (“two authors who are famously given to those sorts of things”) but “he’s not just interested in the sex or the fart jokes and so forth; there’s a lot of social commentary, they’re very artfully made — if you were just hoping for a crudely enjoyable medieval movie, Pasolini’s kind of disappointing in that way. You’re getting weird, 1970s capitalist commentary in your medieval movie.” If you’re looking for a more humorous reimagining of the Middle Ages that’s still not a slave to convention, George recommends The Knight’s Tale featuring Heath Ledger (and Queen). “In theory, I should be shocked and appalled as somebody who used to teach a lot of Chaucer, but it actually is a sort of smart and funny and totally modern, unapologetically modern take.”

This editor, at least, would love to see some weird capitalist commentary in her medieval movies. For a character as seemingly radical as Robin Hood, I’ve been pretty disappointed by the lack of revolutionary sentiment in all the Robin Hood movies I’ve seen. All these Robin Hoods — from Russell Crowe to Errol Flynn to Kevin Costner — somehow end up fighting WITH the king, not against him. Perhaps it shouldn’t be so surprising to have a conservative Robin Hood. Modern visions of revolution don’t tend to include a king, but that’s not necessarily true of medieval radicalism. “That’s a natural sentiment for us, but that’s generally not what medieval revolutionaries wanted,” George told me. “The king is this sort of sacred thing that keeps it all together, and very few of them can imagine a world without one.”

Then again, maybe that fascination with the monarch hasn’t gone away as much as we might think. We keep putting the royals on screen, whether that’s in Prince of Thieves or The Crown: “You can look to other media and say we’re still sort of fascinated and fawning over British royals… there’s some criticism, and maybe some gratitude that this isn’t really the world we live in, but at the same time we are kind of awed and fascinated by these kings.” Take the 21st century giant of Medieval-inspired TV, Game of Thrones. Both George and I couldn’t help but notice that “Game of Thrones is in a lot of ways a profoundly conservative view of the world.” Starks? Lannisters? Targaryens? All nobility. Sure, there might be some modern elements — “We like to have certain kinds of gender norms be upended, and that is a place where I think our kind of more revolutionary stance towards medieval material is more consistent, and even true in something like Game of Thrones” — but by and large, “the political order, the place of capitalism, the kinds of structuring narratives — they’re pretty conservative.”

Is the modern imagination lacking?

In some ways, modern filmmakers and screenwriters seem to pick and choose the elements of medieval narratives that they want to make progressive. “I would argue that in a lot of ways, a lot of medieval literature is more queer than we would give it credit for, and that actually, it’s queerer than the heteronormative versions that modern film and TV produce,” George said. Modern reimaginations of the Middle Ages are sadly lacking in gay romance. “There are plucky independent women, for sure, and women who refuse to be married off — things like arranged marriage, we just can’t tolerate… but the sort of broader traditional sex roles, there doesn’t seem to be the imagination to always overthrow those”

This lack of queerness was something we both found disappointing about The Green Knight. There’s a point in the original poem, when Gawain is staying at a certain Lord’s castle, where the two make a bargain: when the Lord gives Gawain his hunting spoils each day, Gawain will have to exchange with him anything that he’s received in the castle that day. So, when the Lord’s wife makes a move on Gawain, you can imagine the questions it raises. “What if Gawain does have sex with the Lord’s wife, and then is responsible to ‘give his winnings’ back to the Lord? Could he have sex with him? It’s a question that the text doesn’t ask, but it’s right there to be asked, and I don’t think the movie goes there in the same way, and that to me is a missed opportunity — and again, one more sign of a way in which some of our thinking about medieval texts is bound more by convention than we’d like to think.”

Even the aesthetics of the genre seem to be tied to convention. “I was joking with somebody else the other day, The Green Knight is a medieval movie so you can expect fog,” George said. “The Middle Ages just seem to have had a whole lot more fog, and slate gray, cold, drizzly skies, and it’s like, you know, they had the Middle Ages in Southern France too.” Beyond the strangely monotonous weather, I wondered if all the extras in these movies might be sharing stock wardrobes: grayish-brown pants, greenish-brown tunic, brownish-gray cloak, and of course those weird, perpetually dirty fingerless gloves that they all seem to be wearing for some reason. I’m no expert, but I’m pretty sure that colors weren’t invented in the 20th century. “I’m not here to say that there’s something profoundly unrealistic, or that they’re getting it wrong,” George added, “but I mean, I imagine if we could magically transport ourselves back to medieval Europe, you could see a lot of different things. It didn’t all look the same.”

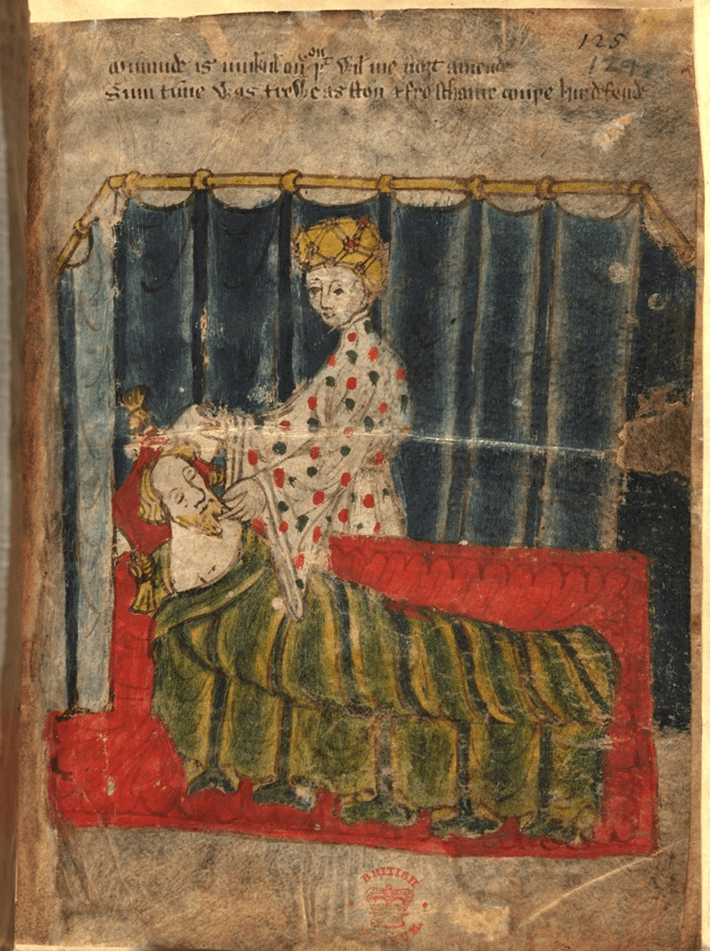

(From British Library Cotton MS Nero A X)

At least there’s heart behind it, though.

A lot of these medieval movies seem to be some sort of labor of love. “I think a lot of these filmmakers, they do get drawn to these medieval stories because they’ve actually read them, you know, it’s not as though somebody’s just handing them a kind of script that’s been fed through some mindless mill, which does seem to be how Marvel movies get made.” (The views and opinions expressed in this interview are George’s own and do not reflect the opinions of the Second Laird Miscellany… Just kidding. They do. Fight me.)

As for the future of medieval drama on screen, George thinks that streaming services are the ideal place to capitalize on the niche of people for whom medieval times are enough to turn on the TV. Will he be watching them? Maybe an episode or two, but to be honest, when you’ve seen one episode of Vikings, you’ve seen them all. “I don’t say all that to sound like these medieval adaptations are boring and I don’t like them; I think I probably like them about as much as anybody else does. But we are kind of commenting on an inherent kind of conservativism” — and that just doesn’t do justice to the source material:

“One of the things I like about medieval literature is how weird it is.”

Here’s hoping Hollywood gets the memo.

Comments

What would George say about Shrek?

George would say that he likes Shrek! Although some of what he said about the general conservativism inherent in Hollywood medievalism certainly applies to that movie too.