Vern Bailey fearlessly led a group of us through London in the first few months of 1992. We stayed in a narrow hotel with uneven floors and spent our daily budget of nine pounds sterling on hummus and wine and jaffa cakes and theater tickets. For a good chunk of us, it was our first time out of the country; what did we know? Weetabix was exotic and the cider alcoholic and it’s no wonder we were studying adaptation.

Vern Bailey fearlessly led a group of us through London in the first few months of 1992. We stayed in a narrow hotel with uneven floors and spent our daily budget of nine pounds sterling on hummus and wine and jaffa cakes and theater tickets. For a good chunk of us, it was our first time out of the country; what did we know? Weetabix was exotic and the cider alcoholic and it’s no wonder we were studying adaptation.

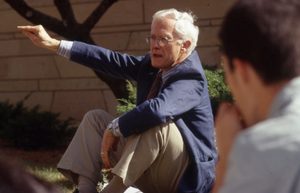

We followed Vern through the British Museum, to the National Theatre, the National Film Theater, Camden Ices, to Stonehenge, which had closed for the day (gods and monsters clock out at 4:30), to Bath where we acted out all of our Jane Austen fantasies (fainting spells and sprained ankles). He led us to Stratford-on-Avon and then to Maryon Park where we played tennis and looked for murders hidden in the photos we shot. There were the narratives he was teaching us and the lives we were leading and the dialog between the two: he was showing us the many different ways a life can be lived and recorded on film, in scripts, and through prose. We kept journals in longhand — there was no Facebook status to update, no tweets to be chirped. This was before cellphones, before the internet—and human communication was actual and not virtual.

Back on campus, the adventures continued. He dunked us in Italian Neo-Realism and dusted us with Demme but Vern Bailey is synonymous in my mind with Hitchcock. We drilled down on almost every one of his films, studying the flight path of a crop duster shot by shot, how a crashed carousel is reflected in broken glasses, what is, to me, the best kiss ever captured on film, and of course, that shower scene. On the surface, a portly Londoner has little in common with a Midwest maven but in practice, Hitch and Vern were exacting and precise, they shared a wicked sense of humor, and both had little patience for stupidity. Vern gave me a job when I badly need one during the summer—organizing and reorganizing the endless VHS tapes in his office, a job that not only came with money but also a twelve-inch screen that was constantly on. It was there that we watched a bootleg Kieslowski and we argued with sense and sensibility over different performances until each day lay in remains.

It was a relationship that lasted decades past Carleton, and I owe a good chunk of my career as a screenwriter to Vern Bailey. To the stories he broke open for me, and the ways he taught me to not only see a film but create one. I internalized his standards, a barometric pressure I apply to narrative possibilities when I’m writing: what would Vern think? Not that he would ever tell you outright, of course. What good is polite reserve if you can’t deploy it at will?

When I graduated, he gave me a survival kit for a Los Angeles life. It was very practical; in it was a whistle, a compass, and a pocket knife. I have used them all in various and occasionally Hitchcockian ways. Even as I type this, the pocket knife rests within reach, folded in my desk drawer.

Vern Bailey was, in short, all you could hope for in a professor, a friend, and a mentor. He was the gateway drug to the rest of my life.

In London, he also took us to Tintern Abbey where we stood in the rain and read Wordsworth’s poem there. I don’t remember much about the poem, but I do remember the decaying abbey dotted in bright green moss and the feeling of walking where others had once, a very long time ago. The poem, it turns out, is about the awe-some power of nature, and how it is an expression of the divine. A spirit that rolls through all things. Not unlike the immortality a professor can achieve when his ideas live on in us.