On this winter’s English Theatre & Literature in London program, students enrolled in a 3-credit Urban Arts course, for which they each designed and executed an independent arts project that required them to engage with the city of London in some way. In the coming weeks, the Miscellany will feature several students’ work from this course. Last time, we featured Mina Wolf’s children’s book Percy Pigeon’s Adventures in London, and next up is Austin Showen (’16), who creatively reconstructed the history of an 1890 edition of a Dickens novel.

What was your Urban Arts project?

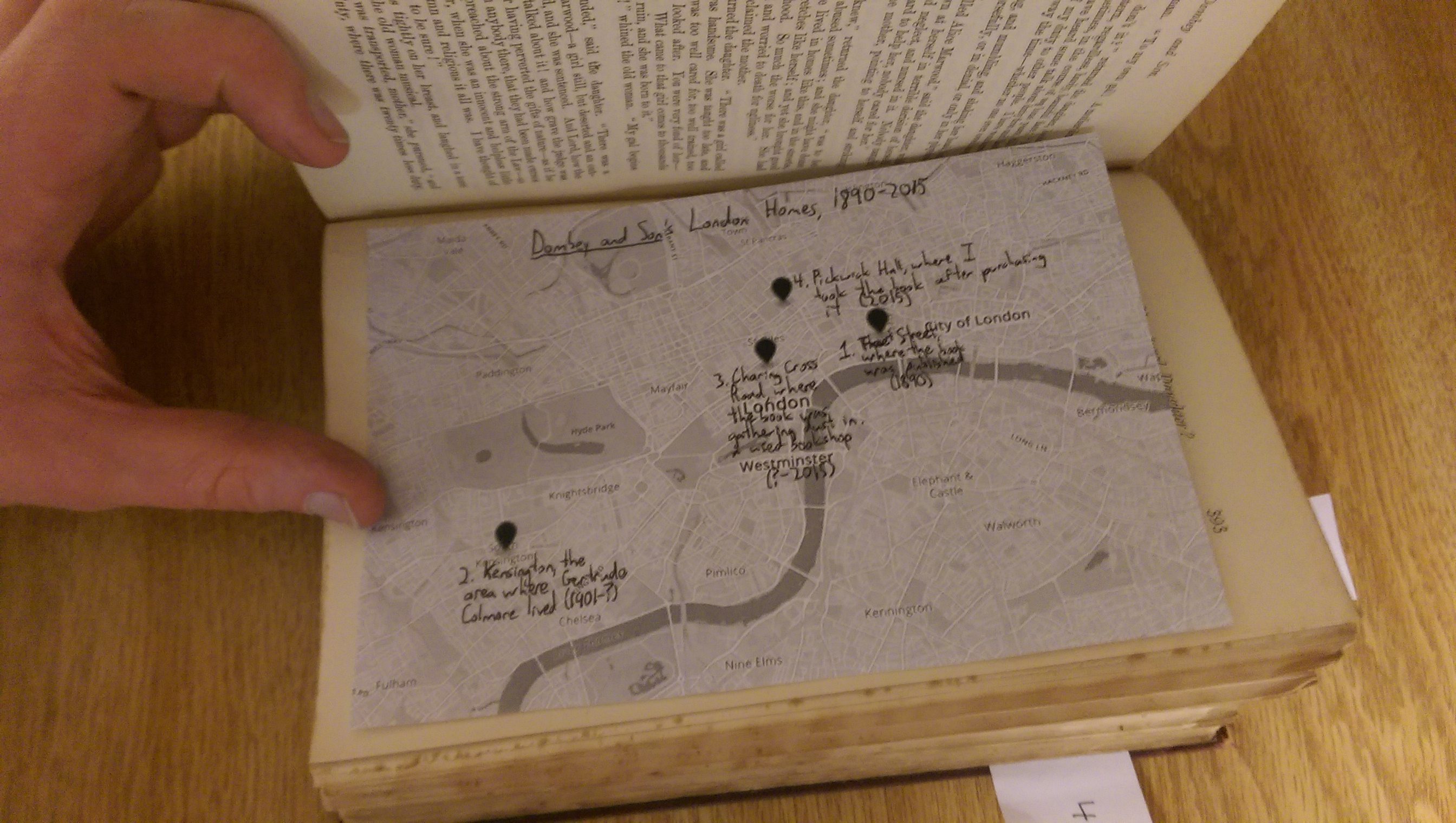

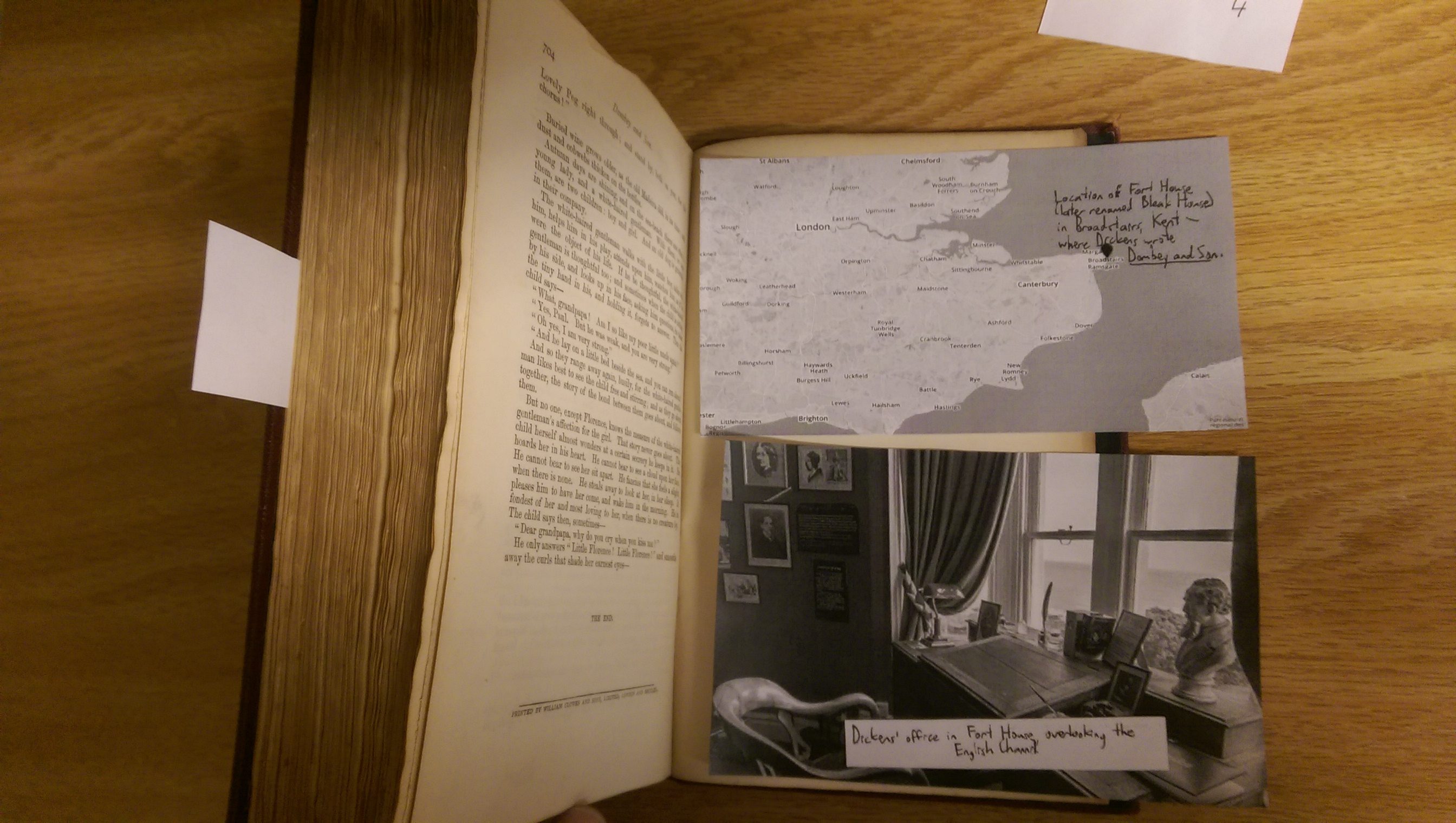

I found an 1890 copy of Dickens’ Dombey and Son that seemed to have an interesting history, and reconstructed its story from publication to the current day. I based my project – which was mostly creative writing, but which also incorporated some maps and photographs, as well as the book itself – on physical details of the book, research into its past owners, and my own imagination. The final product had pieces of writing from the point of view of Dickens, the previous owners, and a third-person narrator, the physical book being the common element that linked these stories together.

Where did the idea for this project originate?

I spent a lot of time shopping for old books in London, so I was thrilled when I found this copy of Dombey and Son at a used bookshop on Charing Cross Lane, on sale for only £2! After I bought the book, I found a note in the front cover, in beautiful handwriting, saying, “Gertrude Colmore, from Violet Barker. Xmas 1901.” I looked up the name Gertrude Colmore on a whim, and found out that there was a suffragist writer by that name who published a book called Suffragette Sally in 1911. Based on what little biographical information I could find, I determined that she lived in London for most of her life, so the book was very plausibly hers. Once I found that out, I knew that I wanted my project to be based on this book.

What was the process of working on the book like?

To start out, I plunged into the book, searching for every little physical detail that might help me reconstruct the book’s history. For example, I noticed right away that the pages in the first half of the book were still bound together, but the pages in the second half had been cut apart. In the story that I wrote about the book, I imagined that this was because Gertrude Colmore had read the first half of Dombey and Son when it was published, so when she received the book in 1901, she picked up where she had left off. I had a lot of fun creating details like this to fill in the gaps in the story. Once I had written all the content I had time for (and if I had had more time, I could have kept going forever), I placed different portions of the story in different parts of the book, with maps and pictures accompanying certain pages. Anyone could have done it! I was just lucky enough to be in the right bookshop on the right day.

How did the project connect to other academic work on the London program?

On a basic level, we read Dickens’ Bleak House as part of the program, and I drew heavily from Dickens’ themes and style in my project. Additionally, in all of our classes in London – especially our Walking London class with the fantastic Cambridge professor, Brian Murray – we discussed the importance of place: for Dickens, overlooking the ocean in his office in Broadstairs, water will inevitably be a major theme of his writing (as is the case in Dombey and Son); for Gertrude Colmore, writing in her journal in Kensington, upper-middle-class social standards will inevitably be a focus. As I traced the book’s journey from Dickens’ desk to my hands, I tried to constantly reflect the physical location of the book and of the writers whose voices I was emulating.

How did the project help you to connect to London?

This project made me realize that history is everywhere in London, as long as you know where to look. I bought, I think, eleven or twelve old books like this one in London, and although none of the others have the names of their past owners written helpfully in the cover, every single one must have had an interesting past. To turn a £2 book into a tiny piece of history, all I had to do was to slow down and ask myself what the story behind the handwritten note could have been, or why half the pages were still bound. I realized, then, that I could learn a lot by asking questions about other things in the city, too: how a certain piece of art ended up in London instead of its country of origin, why a certain statue is where it is, or why a certain building looks so different from all the buildings around it.