Over the weekend, the Carleton Players performed A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Under Andrew Carlson’s direction, the production brought colorful, neon light to what has been a cold and morale-testing term for many. In Act V, Theseus, played by Ali Purdum, commented on the description of Pyramus and Thisbe, “‘Merry’ and ‘tragical?’ ‘Tedious’ and ‘brief?’”, a moment which defined what was at the heart of this production: the interplay of playful, over-the-top camp and sincere emotion. Midsummer does not allow itself to be taken too seriously; we need look no further than the wildly exaggerated Bottom and his bumbling fellow players to see this. The love-struck nobles have a tendency for the dramatic and the irrational that borders on absurdity, and the fairies are a thing of sprightly fancy and imagination pulling the strings behind it all. The silliness of this play proves to us that we are all subject to folly, and especially in love. But, while playing up the whimsical melodrama of the play, the Players production also allowed space for melancholy and sincerity, and brought important ideas about gender and class into a contemporary light.

As the viewing experience was through live stream, the actors were in an empty theater, giving a starkness and stripped-back quality to the play that might not have been the case had there been a live audience. The set was sparse, using one primary structure and sprinkled with the occasional piano, bed, industrial ladder, and, of course, wall. The lighting, designed by Tony Stoeri, switched between the cold white light of the court, and the sensual purples and pinks of the forest, clearly distinguishing, as is usually done, between closed world and green world. But, in this particular case, the lighting went hand in hand with another crucial aspect of the production: the frequent instances where characters would burst into renditions of nostalgic 80s pop songs.

Music operated in this production in the way it does in other Shakespeare plays, as a mode of amplifying emotional expression. The 80s nostalgia both lent itself well to the exaggerated nature of the play’s characters, and simultaneously brought a lot of heartfelt emotion which added complexity to many roles. The glistening cheesiness of many of the lyrics, mixed with the sincerity of the way they were sung by the actors, led the audience to laugh at the absurdity of love and the embarrassing lengths it will make us go to let our feelings out. And yet, while Bryn Battani’s wistful piano ballad as Helena was humorous, especially with Demetrius walking past, playing with his hair, the scene was also… rather sad. The audience could easily visualize Helena’s unrequited love. The contemplative, longing rendition of “Time after Time” at the very end of the play might remind the audience of how long our lives have been affected by Covid-19, how difficult it is to make sense of time these days, and the precarious future ahead. In general, the frequent use of dance-pop seemed an intentional reminder of the very things Carleton students are missing right now, like live music performances at the Cave and dancing in big crowds at Sproncert– those quintessential doses of Carleton magic that we have had to recreate in much smaller or virtual ways.

The ballads were well-selected for characters. Demetrius’ fewer lines sometimes makes it harder to get inside his head; therefore, the decision to have Demetrius, played by An Vong, serenade Helena at the end gave more emotional versatility and depth to his character, and proved a potentially more genuine love for Helena than merely the magical properties of Puck’s flower. The Players also chose to go a similar route with Oberon, played by Jaxon Alston. After being awoken from her dream state in which she seduced a donkey, Lauren Bundy, as Titania, did not take Oberon’s hand, and remained upset as Oberon urged her to give up their quarrel, which was a very insightful decision– rightfully so, after he tricked and mocked her in a pretty manipulative fashion. Noticing her reticence, Oberon began to plead for her love, trying to get her back with “Purple Rain,” which I think humanized him well, and revealed that this kingly character whose primary strong emotion seems to be anger can also be played quite vulnerably. And Titania’s response, in eventually joining in the ballad, was really beautiful. Set against the moody purple and pink background, while a sequin-y rain fell, this scene was cinematic; it was over-the-top, but in the best way. It showed the power of a good song to really bring out true feelings.

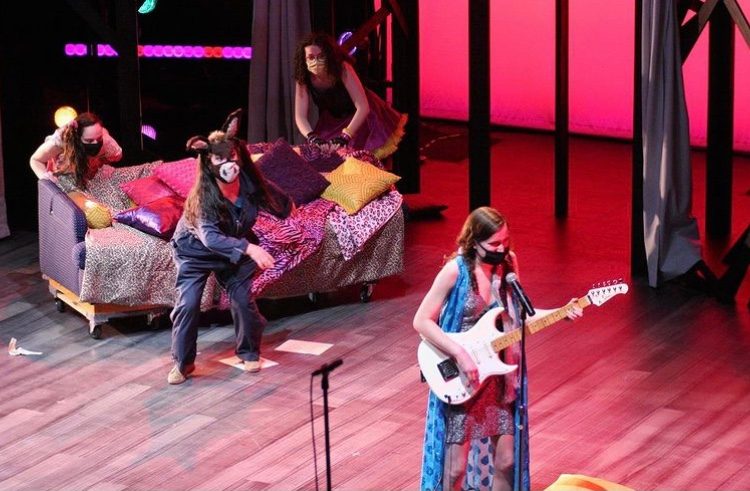

Several of the pandemic-related choices in the production also worked towards the same effect of the duality of sincerity and comedy in the play. For one, because of the mask restriction, movements had to be all the more grandiose, for gestures had to essentially replace facial expressions. There was lots of good physical acting. Some particular highlights were Titania playing an electric guitar, Izzy Anderson’s extremely long and hilarious “Die!” sequence as Bottom, Helena’s playing up of her “I am your spaniel” moment into a potentially raunchy role-play situation, and Karina Yum, as Francis Flute, giving a strikingly sincere performance as Thisbe.

In addition, the live stream employed the use of three different camera angles, which allowed us to see more perspectives than we would normally be allowed to. When characters spoke with knowing glances directly into the camera, breaking the fourth wall on screen, it almost felt like we were on the set of an 80s music video. The costuming, designed by Mary Ann Kelling, added to this feeling as well. Actors donned vests, suspenders, 80s-style suits, Mom jeans, and heals.

The production’s gender inversions were also crucial. For one, the working class rude mechanicals were nearly all played as female characters, and their theme song of Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5” was a great fit. The slapstick-style funny woman is not really a Shakespearean trope in the way it is for men, so it was great to have that change. In addition, the gender reversals of key characters such as Bottom and Lysander, played by Alli Palmbach, allowed for several lesbian relationships to take center stage. Costuming, designed by Mary Ann Kelling, was quite androgynous on the whole, and the lovers who ended up together shared similar costume styles, which in turn cut down the effect that heavily gendered costuming can have on assumptions about roles in relationships. In fact, Puck, played by Hannah Sheridan, seemed unable to distinguish Lysander’s gender identity. Though played as a female character, Lysander was mistaken by Puck for an Athenian man, and, if I am not mistaken, Hermia also referred to Lysander as “Lord” one or two times. There was playfulness in these decisions, but also clearly lots of critical work had been done to reimagine the borders of gender and sexuality in the play.

From Jaxon Alston and Bryn Battani’s incredible vocal performances, to Elaina Boyle and Esme Krohn’s wonderfully nervous, deadpan acting as Wall and Moonshine, the Carleton Players’ production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was full of character, and stayed true to Theseus’ meta-theatrical line; it was both merry and tragical, and illuminated how, even at his most comedic, Shakespeare manages to explore a vast palette of human emotions.

All photos from Mary Ann Kelling in the costume department.